The Illusion of Conscious Will

/ Wow, isn’t it ironic that I sometimes want to write about something but can’t find the words. It’s actually so common an experience that we hardly even notice the irony. It’s as if I have to not care too much to be able to write. I have to let go, or trick my conscious will out of the way to improvise the actual text through my fingertips. Martial arts have similar requirement; and healing does too. I suppose that letting go is the fruition of non-conceptual meditation. Is the ability to improvise is an indicator that a person is seeing things as they actually are?

Wow, isn’t it ironic that I sometimes want to write about something but can’t find the words. It’s actually so common an experience that we hardly even notice the irony. It’s as if I have to not care too much to be able to write. I have to let go, or trick my conscious will out of the way to improvise the actual text through my fingertips. Martial arts have similar requirement; and healing does too. I suppose that letting go is the fruition of non-conceptual meditation. Is the ability to improvise is an indicator that a person is seeing things as they actually are?I generally don’t like psychology much. Perhaps it is because I have a tiny lingering unconscious desire to do damage to the psychiatrist I saw from age 4 to 7. In my 20’s I went back and found that very psychiatrist. My mother, my father and the psychiatrist all have different explanations for why it was desirable to sequester me twice a week in a room with a desk and venetian blinds. Not only was communication lacking in the process, but no one could agree on what the intention was. It makes me wonder whether agreement is actually a significant factor in cases of consensus activity, even in situations where people say they agree.

How do we know what we know? What causes unconscious behavior? How do we attribute agency? Asian arts present us with a challenge in that they are rooted in a cosmology which presumes that all agents are mutually self-re-creating. Is the art making me? or am I making the art?

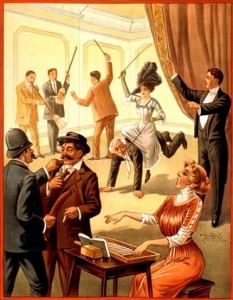

So with all that in mind I recently read The Illusion of the Conscious Will, by Daniel M. Wegner, which is an exploration of how conscious will effects our actions. It is a very wide ranging survey of mostly psychological studies and experiments dating back to the 1800's, with some anthropology and neurology studies as well. With an eye to exposing the mechanism of conscious will and how it interacts with spontaneous action and unconscious action; the book explores multiple personalities, hypnosis, trance possession, and many other more mundane ways in which we doubt whether a persons actions are consciously willed.

Chew on this:

Perhaps the experience of involuntariness helps to shut down a mental process that normally gets in the way of control. And, oddly, this mental process may be the actual exercise of will. It may be that the feeling of involuntariness reduces the degree to which thoughts and plans about behavior come to mind. If behavior is experienced as involuntary, there may be a reduced level of attention directed toward discerning the next thing to do or for that matter, towards rehearsing the idea of what one is currently doing. A lack of experienced will might thus influence the force of will in this way, reducing the degree to which attention is directed to the thoughts normally preparatory to action. And this could be good.

The ironic process of mental control (Wegner 1994) suggests that there are times when it might be good to stop planning and striving. It is often possible to try too hard....

He concludes that conscious will is an illusion, we feel like we are willing our actions because our actions usually correspond with our experience of willing them, not because our conscious will actually causes our actions. But conscious will is like a compass on a boat. It tells us where we are going, makes us feel guilty so that we change course, or proud so that we charge ahead. It manages our preferences.

He concludes that conscious will is an illusion, we feel like we are willing our actions because our actions usually correspond with our experience of willing them, not because our conscious will actually causes our actions. But conscious will is like a compass on a boat. It tells us where we are going, makes us feel guilty so that we change course, or proud so that we charge ahead. It manages our preferences.Re-reading what I just wrote, I imagine it is hard to follow. This particular conundrum resists language; if you are not in control, how can you change coarse? The book is great because it doesn't rely on philosophical or psychological language, instead, it describes experiments one after another. For instance, when a person wills themselves to not do something, they make themselves statistically more likely to do the thing. Despite my intentions, I always use to throw the Frisbee at my elderly neighbor's window just at the moment when she was looking.

We are not our minds. We don’t actually know what we are. If we use our conscious mind in a fight we will probably lock up or freeze. But that remains an interesting debate. When faced with an opponent who we believe intends to do us harm, what happens to our will? It seems that intent also has a great potential to get in the way of our ability to respond. We talk about intent in internal martial arts a lot. I argue, following Wang Xiangzhai, that if an opponent's intent comes to a point or to a line or a curve, he will be easy to control. Only if my intent is spherical can I really hope to reliably defeat a larger opponent who is trying to hurt me.

No shortage of irony here.

From reviewing the scientific experiments in this book, I find evidence of an active awareness underneath our conscious will. Freud pointed to the Id, a primal self. In Daoist cosmology we refer to a qi body which can act very freely and spontaneously. In observing that this qi body coincides with a person, we could brake all protocol and just call it Laozi, an old baby, (lao=old, zi=baby). This Laozi doesn’t have it’s own stop button. Without the conscious will to inhibit it, it would do silly things like walk off of cliffs or try to squeeze through keyholes. The qi body is both the source and the ingredient of inspiration, but it is not at all articulate. It doesn’t have preferences or opinions or hidden agendas because it has no memory. All memory belongs to the realm of jing, not qi. All inhibition comes from trying to use the mind to control the composite body-structure-memory.

Thus, if we want our jing, our structure body, to be free, it must follow the qi; but if the qi leads, our fighting techniques will stagnate at the developmental level of a 2 year old. So, we say, the spirits (shen) must lead the qi. What are the spirits? Perhaps they are a blend of our imagination and the kinesthetic experience of our environment, without the conscious will?

Thus, if we want our jing, our structure body, to be free, it must follow the qi; but if the qi leads, our fighting techniques will stagnate at the developmental level of a 2 year old. So, we say, the spirits (shen) must lead the qi. What are the spirits? Perhaps they are a blend of our imagination and the kinesthetic experience of our environment, without the conscious will?This is a great book. It isn’t easy to read, but hardly anything I recommend is. Terry Kleeman recommended this book when I met with him at the food court under Ikea in Taipei. I was presenting my theory of Baguazhang’s original connections to Daoist ritual, describing how bagua can be organized around different trance states. He was very friendly and skeptical, pointing out as so many others have, that perceiving Taiwanese rituals in terms of trance is a Western intellectual construction. On the other hand he said that his Daoist priest informants consider their martial arts prowess to contribute to their ritual efficacy and potency.

But back to the book. It is a really good Eastern-Western bridge to understanding why Internal Martial artists talk about experiencing shen (spirit) outside of the body. It also threw me into a spiral of self-doubt. I started asking a lot of, “Am I fooling myself?” type questions. Am I hypnotizing myself? Am I hypnotizing my students?” For this reason alone I would recommend it. I decided that the possibility that I am fooling myself or my students is high. Not all the time, but certainly sometimes. And that’s not always bad either, but ignoring it is a recipe for disaster. I’ve started catching myself in the act of self-hypnosis.

For instance, I was teaching push-hands the other day and I stopped myself from striking a student who was making the mistake of forcing my hand into his head. This is a flaw in my teaching even if I stop and explain it to the student because the student probably won’t learn from his mistake unless he gets hit. But even worse, it’s a bad habit because I’m training myself to not hit in certain situations. So whether in the dojo or the cafe, beware of nice people! Only princes, psychiatrists and con-artists are charming! The next time he made that mistake I clocked him.

Now that I’ve done all this writing, by tricking my conscious will out of the way, I’m going to re-establish control, good-bye.

A review of:

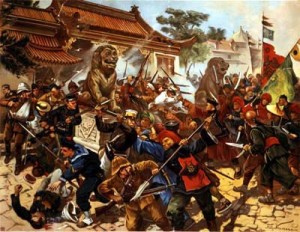

A review of:  The first section is only 42 pages long and starts off pointing out that, most people know more details about the Boxer Uprising than they do about the Taiping rebelion, even though the scale of the Taiping Rebelion (20 Million dead over 20 years) dwarfs that of the Boxer Uprising (10's of thousands dead over a year or two), and Taiping was led by a man claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. He then recommends people read

The first section is only 42 pages long and starts off pointing out that, most people know more details about the Boxer Uprising than they do about the Taiping rebelion, even though the scale of the Taiping Rebelion (20 Million dead over 20 years) dwarfs that of the Boxer Uprising (10's of thousands dead over a year or two), and Taiping was led by a man claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. He then recommends people read  Paul A. Cohen does not appear to be a martial artist or a person with a performing background, so he doesn't go into depth with either of these. However, he makes it clear that martial arts and theater were always part of the mix.

Paul A. Cohen does not appear to be a martial artist or a person with a performing background, so he doesn't go into depth with either of these. However, he makes it clear that martial arts and theater were always part of the mix.  I just finished reading Paul A. Cohen's book,

I just finished reading Paul A. Cohen's book,  The book is a translation of a short manual about Xingyi training from the 1920's, supposedly used by

The book is a translation of a short manual about Xingyi training from the 1920's, supposedly used by The introduction of Rovere's book claims that the famous martial artist's Sun Lutang and Wang Xiangzhai both taught for the

The introduction of Rovere's book claims that the famous martial artist's Sun Lutang and Wang Xiangzhai both taught for the  Nearly half of

Nearly half of