Internal martial arts, theatricality, Chinese religion, and The Golden Elixir.

Books: TAI CHI, BAGUAZHANG AND THE GOLDEN ELIXIR, Internal Martial Arts Before the Boxer Uprising. By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($30.00), Digital ($9.99)

Possible Origins, A Cultural History of Chinese Martial Arts, Theater and Religion, (2016) By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($18.95), Digital ($9.99)

Watch Video: A Cultural History of Tai Chi

New Eastover Workshop, in Eastern Massachusetts, Italy, and France are in the works.

Daodejing Online - Learn Daoist Meditation through studying Daoism’s most sacred text Laozi’s Daodejing. You can join from anywhere in the world, $50. Email me if you are interesting in joining!

The Master Key

/The sound quality on this podcast of Rory Miller is poor, but it is still a fun talk. (I'll come back to it in a moment.)

I was talking to Daniel Mroz yesterday and he said that his friend who is a Beijing Opera (Jingju) master of martial arts roles made a very bold statement. He said that there is a basic movement of the whole body, making a flower with the hands, which is the master key movement out of which all other Beijing Opera movement comes.

This particular movement is nearly identical to a basic movement used in Kathak (North Indian Classical Dance). It is also important in Filipino knife fighting Silat, Maija Soderholm showed it to me the other day. George Xu uses identical whole body coordination as his favorite warm-up for teaching Chen Style taijiquan but working from a horse stance.

The movement is probably essential for anyone who masters handling two single edged blades at the same time.

Now that I've had a day to play with it as a key concept, I'd say it is key to all Baguazhang and is very helpful to staying integrated during shaolin movement. It is not key to Liuhexinyi, but I may change my opinon on that. As an underlying integration of right to left and homo-lateral to contra-lateral symmetry it can be used as an internal measuring stick of whole body integration in almost any complex movement.

I've been doing it for 25 years, but I never thought of it as a key movement before.

I read one of Namkhai Norbu's books last fall in which he recommends using the Vajra posture for standing until one is past the experience of fatigue before laying down and relaxing into emptiness as a way of going directly to the experience/expression of Dzogchen (non-conceptual enlightenment). Basically the Vajra posture is the same posture used for this movement in Kathak dance. It all fits together so well. And the term Vajra means a weapon of uncuttable substance, like diamond I guess. I also recently read an article by Meir Shahar about the widespread concept among martial artists in pre-20th Century China of creating a Vajra body. Here is the title (you can get it for free if you have access to JSTOR):

- "Diamond Body: The Origins of Invulnerability in the Chinese Martial Arts." In Perfect Bodies: Sports Medicine and Immortality. Edited by Vivienne Lo. London: British Museum, 2012.

So all this is to preface that I met Adam who runs West Gate Kungfu School here in Boulder, Colorado. We hit it off right away. We both care deeply about the arts and we both see performance skills and having maximum fun as master keys of the martial arts experience. He invited me to hang out with his performing troupe the other day. I brought my instruments and accompanied their warm-up routines, which went really well, I also taught some Daoyin which they immediately wanted to teach to the kids classes. I had a great time and I have deep sense of respect for what Adam is doing.

His students have a lot of talent and enthusiasm and they have some great butterfly kicks too! Butterfly kicks, by the way, use the exact same body coordination as that Vajra flower movement I was just talking about above.

So I was an argument on Facebook with a Police Officer about whether or not Capoeira is utilitarian in a self-defense context. He was particularly adamant that flips are useless for fighting. I eventually got him to agree with me, which was awesome because he is obviously a really smart and experienced guy. To win the argument I went through some of the stuff you can hear in that Rory Miller talk at the top of this post. For instance, martial arts training rarely, if ever, kicks in the first time a person is in a violent situation. It is more likely that it will kick in after 3-5 violent situations. And when it finally does it can be amazing. But before that it is all conditioning and that includes what you conditioned as little kid. From a purely self-defense point of view having a lot of techniques to choose from forces a person into his or her cognitive mind which generally precipitates a whole body freeze. So one of the most important things martial artists need to train if they care about self-defense is breaking that freeze.

Conditioned movements should be designed relative to what a person is likely to need. This is very different for a police officer who may have a duty to get involved, and a citizen caught in a self-defense situation. Criminals most often (this material comes from Rory Miller) attack children and women from behind, and surprise attacks are also most often from behind. The practice of doing a back flip involves moving huge amounts of momentum backwards and up. If the attacker is taller than you are, your head is going to slam into either his chin or his nose, and you will probably both end up on the ground. The motion of a back flip is actually a really good thing to condition as a response to a surprise attack from behind.

In general, practices which use large amounts of momentum, practices which condition comfort and ease with flying through space are great for self-defense. Why? because of this maxim: If you are winning try to control the fight, if you are losing add chaos and momentum. If you get attacked by surprise, you are already losing, so add chaos and momentum. The practice of spinning around the room while holding on to a partner is also great conditioning, most judo classes train this a lot. Add butterfly kicks and you are doing even better, practice using those kicks off of walls and tables and you are approaching ninja territory.

UPDATE:

Someone just posted this on Facebook and it is a great example of the same base movement used to organized a routine:

Performers are Mean People

/ Beijing Opera (Jingju) has as its most basic physical training something called "da" literally hitting or striking. The warm ups I learned as a kid studying Northern Shaolin are the very same ones used in Beijing Opera. The stage roles are divided into either martial or civil categories (wu and wen). Extensive weapons training is given to everyone because much of the traditional repertoire involves depicting historic conflicts and battles. Probably the best piece of evidence is the most famous Chinese Opera star of the 20th Century, the female impersonating dan Mei Lanfeng, studied Baguazhang with one of the toughest internal martial artists of his time! It was said to have improved his sword dance.

Beijing Opera (Jingju) has as its most basic physical training something called "da" literally hitting or striking. The warm ups I learned as a kid studying Northern Shaolin are the very same ones used in Beijing Opera. The stage roles are divided into either martial or civil categories (wu and wen). Extensive weapons training is given to everyone because much of the traditional repertoire involves depicting historic conflicts and battles. Probably the best piece of evidence is the most famous Chinese Opera star of the 20th Century, the female impersonating dan Mei Lanfeng, studied Baguazhang with one of the toughest internal martial artists of his time! It was said to have improved his sword dance.Yet people will tell you that Chinese Opera has nothing to do with martial arts.

Beijing Opera is just one of many forms of physical theater in China. There are urban regional styles like what Jackie Chan studied as a kid and there are rural regional styles. There are also village lineage families, and there are amateur village and regional styles. And within all of those categories there are ritual styles. This is a quick gloss to give readers a sense of the scope--there were probably more than a hundred styles of physical theater in 19th Century China.

But there is a big problem here. Denial.

Jackie Chan has said in variously self deprecating ways that he doesn't know about fighting. And although it is well known that the Physical Theater of the Red Junks was created by the first Wing-Chun masters, it is also reported that they kept their fighting skills entirely separate from their performing skills. Even today tight lines of distinction are drawn---at least in peoples minds---despite the fact that the stances used in fighting and performing are the same, and it is hard to know when a martial arts form has crossed-over into theater.

And everyone knows that Bruce Lee left Hong Kong for the US because he wanted to come here and teach Cha-Cha, right? It's true.

Martial artists go to great lengths to deny any links to performing arts; the "New Life" and other nationalists movements in the 20th Century set out to completely separate martial arts from religious ritual and theater. Sometimes they went ahead and just changed the arts, like Yang and Wu styles of taijiquan. For example, Chen, the older style, is chockablock with pantomime training. Other times they just discarded whole categories of practice, like back bends and high kicks, and sometimes they went for straight faced denial: "No, that movement isn't for cueing the music, it's for poking your eyes out!"

Mean People!

I have not even finished reading David Johnson's new book, Spectacle and Sacrifice, The Ritual Foundations of Village Life in North China, but the chapter on Entertainers is so astounding I just had to blog!

Entertainers (yuehu) were a degraded caste in China. Long time readers of this blog may know that I was deeply shocked and offended by my experiences of caste in India in the 1990's. Chinese culture is not nearly as shocking to my American sensibilities, but then again, I've been studying Chinese martial arts for 32 years and no one has ever spelled it out to me as clearly as Johnson does in his book.

An entertainer had to move off to the side of the road to let "good people" pass.

[Performers] were known as jianmin, "mean people": they could not marry commoners, could not sit for examinations, and could not change their status. In some cases they were required to be on call to the local yamen to entertain at banquets and other occasions. (Just what their responsibilities were is never made clear, but they may well have included sexual services.) They were treated with contempt by the general population....

While there were two major categories of entertainers, there were also castes within castes. The basic categories were coarse (cu) and fine (xi), generally it appears that the coarse played music and the fine played music but also had acting skills.

"Mean people" were used for everything from entertaining visiting dignitaries, to weddings, to the most sacred rituals of a region. "Opera Families" were profane outsiders who lived in separate districts or separate villages and yet were paid to entertain and purify--to bring order and expel evil.

"Mean people" were used for everything from entertaining visiting dignitaries, to weddings, to the most sacred rituals of a region. "Opera Families" were profane outsiders who lived in separate districts or separate villages and yet were paid to entertain and purify--to bring order and expel evil.A caste of hated artists brings to mind Roma (Gypsy) culture in Europe [hat tip to Liu Ming for the analogy]. The "mean people" were considered profane, but they were a necessity for the maintenance of the sacred. Ritual Theater was the most common and widespread religious experience in China before the 20th Century. (Here are some links to previous posts.)

There were many different types of ritual performance throughout the calender year and every single village handled things differently. So it is important to note that amateur commoners performed important roles in rituals and theater, as did Daoist priest, Buddhist monks, Yinyang masters, military personal, local elites, children and even high officials. In fact, I think it is fair to say that some village rituals had a role for everyone.

Which brings us back to martial arts. Martial arts were used extensively in these rituals. It seems almost too obvious that the basic physical training for popular and rarefied physical theater in China was in fact martial arts training. Each region had it's own style of gongfu (kung fu) and it's own style of theater (ci). But the basic training was the same. It could be refined for either fighting, performing, or both.

Which brings us back to martial arts. Martial arts were used extensively in these rituals. It seems almost too obvious that the basic physical training for popular and rarefied physical theater in China was in fact martial arts training. Each region had it's own style of gongfu (kung fu) and it's own style of theater (ci). But the basic training was the same. It could be refined for either fighting, performing, or both.What I've just now realized is that the ideology of modernity functioned in China as a cover for the deep animosity towards the performing castes. These castes are now probably close to extinction. Of course it's risky to generalize, but we now have a better explanation of why most martial arts lineages did everything they could to deny their past participation in ritual performance (lion dance being the big exception). While the entertainer castes were officially liberated, their historic vocation as ritual experts was derided as the root cause of China's humiliations and failures as a nation! I suspect that in some cases individual artists from degraded castes managed to survive by first denying any connection to ritual theater, and then skillfully transforming themselves into pure martial artists.

Now I have to re-think what qigong is in this context. Kind of gives a different meaning to the expression "secret teaching," doesn't it?

(Remember if you are reading this on facebook you can see more images by clicking "original context" below.)

Wing Chun Kung Fu Opera

/ In China, the traveling theater functioned as a subversive organizing tool and a way to hide martial arts training. It was a religious devotional act, watched by the gods (they would literally carry the statues of the gods out of the temples to watch the performances), it was sometimes a ritual exorcism too. The theater was the source of most people's knowledge of history, and it's characters were both gods and heroic ancestors.

In China, the traveling theater functioned as a subversive organizing tool and a way to hide martial arts training. It was a religious devotional act, watched by the gods (they would literally carry the statues of the gods out of the temples to watch the performances), it was sometimes a ritual exorcism too. The theater was the source of most people's knowledge of history, and it's characters were both gods and heroic ancestors.There are various versions of the origins of Wing Chun Kuen but no-one knows for sure as there are no written records as the legend was passed down verbally from master to student.

During the Qing Dynasty period Southern China was in turmoil and many rebellious groups hid there and concealed their true identities from the ruling Qing government. These rebellious groups where supporters of the old Ming Emperors and their descendants, and they sought to overthrow the Qing. Many of them were the survivors of the armies, trained in Shaolin Kung Ku, that were defeated by the Qing. These rebels formed Unions / Associations / Societies as a cover for there activities. One of these Associations was called Hung Fa Wei Gun. This group had a large northern element, including the Hakka people, it was these that started an Opera Troop so they could travel around the country without causing suspicion. They taught the southern people Opera and their Shaolin Kung Fu. After a time the Qing government found out about this and closed the Association down forcibly. It was many years before the people dared to start an Opera Troop again. They eventually did and called the Association “King Fa Wei Gun”. This became a centre for Opera and Martial Arts training. After a few years the King Fa Wei Gun purchased two Junks for the Opera troops to travel around the country.

The rest of the article is here, and there is some more here. (hat tip to Emlyn at Jianghu)

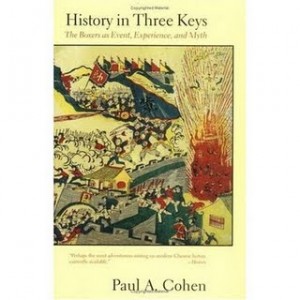

History in Three Keys

/ A review of: History in Three Keys, The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth, by Paul A. Cohen, Columbia University Press, 1997.

A review of: History in Three Keys, The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth, by Paul A. Cohen, Columbia University Press, 1997.So I was doing a little workshop with George Xu last month and he was talking about using Spiritual Fist. Spiritual Fist is what we might call an unconscious level of mastery. Once all the internal and external types of integration, embodiment, differentiation and liveliness are in the right order, they are harmonized by the spirit. That is, we experience the motivation for movement coming from outside the body. This is called Spiritual Fist, or Shen Quan in Chinese.

So I said, "Shenquan? Isn't that what the Boxers called themselves before the Boxer Rebellion?"

"Yes," said George, "That is what they called themselves. True. But all Chinese arts are called Shen at the most advanced levels." And then after thinking for a moment (we were practicing some circular explosive movement during this conversation) he said, "The Boxer's problem was that they lacked Harmony. Right?"

Harmony, I thought to myself, what? Then it occurred to me and I said, "That's what they changed their name to, Yihequan, literally --One Harmony Fist."

George looked perhaps flustered for a moment, but he quickly dropped the issue and moved on to showing us another inner secret.

It was a stunning reminder that ways of knowing and understanding history often do not transcend culture and language. I have no idea what harmony could mean in that context. (Yihequan is sometimes translated, Fists United in Righteousness. Did he mean they weren't righteous? enough?)

__________

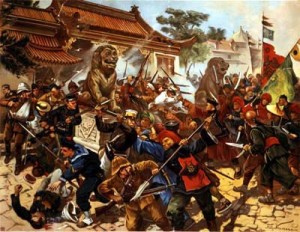

The Boxer Rebellion of 1898-1900 was a bloody uprising in north China against native Christians and foreign missionaries and at times Ching Dynasty Troops. They dressed in Chinese Opera costumes and claimed to be invincible to bullets. Using swords, spears and magic, they took to burning large parts of Beijing, Tianjin and other cities. The boxers were finally put down by foreign troops who took the opportunity to demand concessions and loot the imperial palace.

__________

Paul A. Cohen's book, History in Three Keys, has a simple enough premise which he uses to divided his book into three parts. The first part is his best shot at what actually happened. The facts and documents sorted in such a way as to give the most likely account of what happened. The second part of the book is an account of what people said and thought about the event at the time. The third part of the book is about how the memory of the events lived on and were manipulated in political debates over the next 80 years.

The first section is only 42 pages long and starts off pointing out that, most people know more details about the Boxer Uprising than they do about the Taiping rebelion, even though the scale of the Taiping Rebelion (20 Million dead over 20 years) dwarfs that of the Boxer Uprising (10's of thousands dead over a year or two), and Taiping was led by a man claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. He then recommends people read Esherick's Book, The Boxer Uprising, because Esherick did such a good job of showing the local development of the Boxer Movement. But Cohen puts together an excellent summary of the events and adds to Esherick's take details about the wider effects of the event particularly in the far north. He also includes details on the large numbers of Chinese Christians killed by the Boxers. The largest Christian groups in China were, ironically like the Boxers, both anti-foreiner and participants in mass possession rituals.

The first section is only 42 pages long and starts off pointing out that, most people know more details about the Boxer Uprising than they do about the Taiping rebelion, even though the scale of the Taiping Rebelion (20 Million dead over 20 years) dwarfs that of the Boxer Uprising (10's of thousands dead over a year or two), and Taiping was led by a man claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. He then recommends people read Esherick's Book, The Boxer Uprising, because Esherick did such a good job of showing the local development of the Boxer Movement. But Cohen puts together an excellent summary of the events and adds to Esherick's take details about the wider effects of the event particularly in the far north. He also includes details on the large numbers of Chinese Christians killed by the Boxers. The largest Christian groups in China were, ironically like the Boxers, both anti-foreiner and participants in mass possession rituals.The second section attempts to delve into the mindset and experiences of the people who participated and witnessed the Boxer Movement. In order to do this, my regular readers will love this! he dives into studies of African religion. He does this, of course, as a way to gain perspective on Chinese popular religious practices of possession and trance. (I'm feeling an African Bagua part 3 coming on!)

The entire second section is great. He presents an enormous amount of evidence that, although the Boxer Uprising was a unique event, it's defining characteristics were far from rare. Theatrical presentations were the most widespread form of religious activity in China. So called Chinese Opera is a type of martial arts training. Accounts of trance based forms of conditioning against bladed weapons are found through out the Ching Dynasty. Possession rituals were much easier to do and more common in the north than they were in the south (which explains why Taiwan is not a good model for understanding north China).

In chapter 4 titled, Magic and Female Pollution, he explores the boxer beliefs about women and the wider exceptance of those beliefs across northern China. For instance, when boxers actually got shot and died, or when they tried to burn down a single house they said was owned by Christians and it spread to everyone elses house too, they claimed it was because a woman contaminated the scene. (I can see how this kind of thinking gets started, whenever I have trouble finding something like my keys or a book, I right away blame my half-wife. I mean who else could it be, right?)

The book explores how the Boxers' were viewed by other Chinese at the time in many complex and interesting ways. However, it is safe to say that belief in their magical powers and martial prowess was widespread. Ideas which connect religious devotion, theatrical (Opera) characters, magic, and martial arts were not only widely held; they were the stuff daily life was made of.

The Boxers regularly attributed the casualties they suffered in fighting with foreigners in Tianjin to the latter's placement of naked women in the midst or in front of their forces, which broke the power of the Boxers' magic. The story was also circulated and widely believed by the populace that a naked woman straddled each of the many cannon mounted in the foreign buildings in Zizhulin, making it impossible for the "gunfire-repelling magic" (bipao zhi fa) of the Boxers to work properly....

_______________

Dirty water, as a dextroyer of magic, was unquestionably related in Boxer minds to the most powerful magic-inhibitor of all: women, and more particularly uncleanness in women, a category that, for the Boxers, included everything from menstrual or fetal blood to nakedness to pubic hair. Water was of course a symbol of yin, the primeval female principle in China, and there was a long-held belief that the symbolic representation of yin could be used to overcome the effects of such phenomena as fire (including gunfire), which was symbolic of the male principle, yang. Several groups of rebels in the late Ming had used women to suppress the firepower of government troops. During the insurgency of 1774 in Shandong, Wang Lun's forces used and array of magical techniques, including strange incantations and women soldiers waving white fans, in their assault on Linqing. the imperial defenders of the city were at first frustrated by the effectiveness of the rebels' fighting tactics. An old soldier, however, came to the rescue with this advice: "Let a prostitute go up on the wall and take off her underclothing...we will use yin power to counter their spells." When this proposal was carried out and proved effective, the government side adopted additional measures of a like sort, including, as later recounted by Wang Lun himself, "women wearing red clothing but naked from the waist down, bleeding and urinating in order to destroy our power."

Such magic-destroying strategies were clearly well established in Chinese minds. The nurse who took care of the famous writer Lu Xun when he was a little boy once told him the following story about her experience with the Taiping rebels: "When gorvernment troops came to attack the city, the Long Hairs [the Taiping] would make us take off our trousers and stand in a line on the city wall, for then the army's cannon could not be fired. If they fired then, the cannon would burst!"

Paul A. Cohen does not appear to be a martial artist or a person with a performing background, so he doesn't go into depth with either of these. However, he makes it clear that martial arts and theater were always part of the mix. Here is an excerpt from an article about a famous martial artist whose martial arts family were leaders of the Boxers. That means that in addition to being Traditional Chinese Medical Doctors, bodyguards and caravan guards, they performed magical spells to protect themselves while killing Chinese Christians, while dressed in Chinese Opera costumes, possessed by hero-gods of the theater.

Paul A. Cohen does not appear to be a martial artist or a person with a performing background, so he doesn't go into depth with either of these. However, he makes it clear that martial arts and theater were always part of the mix. Here is an excerpt from an article about a famous martial artist whose martial arts family were leaders of the Boxers. That means that in addition to being Traditional Chinese Medical Doctors, bodyguards and caravan guards, they performed magical spells to protect themselves while killing Chinese Christians, while dressed in Chinese Opera costumes, possessed by hero-gods of the theater.Pei Xirong was born in 1913 in Raoyang county in Hebei province. His father was a core member of the Yi He Tuan [the Boxers], and his mother had also participated in the ‘Red Lantern’ movement [the female part of the Boxers movement, dealt with extensively in Cohen's book]. His uncle, Qi Dalong, was a bodyguard in the caravan agency established by Li Cunyi who guarded caravans traveling between Tianjin and Gubeikou. When the Allied Forces invaded Tianjin, he and Li Cunyi battled against the invaders at Laolongtou Train Station. He fought courageously, sustaining several wounds.

The third part of Cohen's book is also good. (I quoted from it twice in my review of Rovere's book about xingyi in the Chinese army.) It deals extensively with the process of internalization and self-torturous humiliation that came to produce the modern ideas about pure Martial Arts and the guoshu movement (national arts).

One reason this is personal to me is that in the period directly after the Boxer Uprising, my first teacher's teacher, Kuo Lien-ying studied and performed the roll of monkey in Chinese Opera as a teen-ager. The character/god of monkey was one of the most common gods to possess the Boxers during battle. Kuo also competed in Leitai fights (staged on a platfrom), he could still sing Opera parts 70 years later, and he was still doing drunken monkey gongfu too. Kuo was part of the pure martial arts movement, and guoshu, and an early student of Wang Xiangzhai. He worked as a bodyguard too. And he could tie a rope dart around his chest under his coat and shake in such a way that the dart would fly out and stick into a tree. And he could tie up any of his actively resisting students with the same technique. None of his students learned the rope dart. And the one student who learned drunken monkey no longer practices. I think we owe it to the last generation, who brought these fantastic arts to us, to try an recover as much of the full picture as we can.

The last section of Cohen's book deals with the Cultural Revolution. It has a few interesting facts. Probably the most prominent cultural reference to the Boxers during that time, a time when George Xu was fighting in the streets on a daily basis, was a play called Shen Quan, Spiritual Fist.

If we are ever going to have a chance of understanding what the origins of Chinese Martial arts are, we are going to have to drop the stories of purely rational martial tough guys. There is still so much that can be recovered from these arts, because they were designed as storehouses of knowlege. Perhaps, once upon a time, there were legitmate arguments for dicarding central aspects of the tradition, but now, that time has passed. Nobody believes anymore that womens' underpants can protect them from bullets. It's time to see the whole thing for what it is and what is was---a deeply religious, theatrical, health sustaining, fighting arts tradition.