The Origins of the Boxer Uprising

/ The more I think about it, the more I like Joseph W. Eshrick's The Origins of the Boxing Uprising. He published this book in 1987 (UC Berkeley Press) and the fact that I hadn't read it before now, shows where the holes in my (self) education are. (Please feel free to suggest related books in the comments, even if you think I have read them, I'm sure my readers will be appreciative too.)

The more I think about it, the more I like Joseph W. Eshrick's The Origins of the Boxing Uprising. He published this book in 1987 (UC Berkeley Press) and the fact that I hadn't read it before now, shows where the holes in my (self) education are. (Please feel free to suggest related books in the comments, even if you think I have read them, I'm sure my readers will be appreciative too.)I suspect by now my regular readers join me in being easily offended by the lack of scholarship and basic questioning in the history sections of most martial arts books. While we are justified in finding this failure inexcusable, we must answer this question: Why would 20th Century martial artists deliberately obscure their history?

In the process of explaining the origins of the Boxer Uprising of 1899-1900, Eshrick gives us many clues which will help us understand what martial arts were in the 1800's. Let's first imagine that the same individual people took on at least three of the following if not all of the following roles:

- Performing Chinese Opera

- Practicing Martial Arts

- Devotees of Martial Deities or other heterodox (fanatic) cults

- Bandits (Rarely robbed their own villages, which meant that in places like Western Shandong province people often thought of their neighboring villages as being full of thieves.)

- Officially organized volunteer militias

- Anti-bandit gangs (These were created because official militias couldn't cross provincial boundaries, much like American Sheriffs can't cross state lines.)

- Political Rebels and Revolutionaries

20th Century people who wanted to create revolution, preserve religion, train martial arts, or perform opera, all had incentives to cover up the connectedness of these historic endeavors; to claim they were always separate and to attempt to reform traditional practices so that they would appear to have always been separate.

20th Century people who wanted to create revolution, preserve religion, train martial arts, or perform opera, all had incentives to cover up the connectedness of these historic endeavors; to claim they were always separate and to attempt to reform traditional practices so that they would appear to have always been separate.Everyone wants to say that their system of martial arts was used exclusively by bodyguards. No one wants to say their martial art was developed by a group of Opera performers who practiced in secret over generations in order to train groups of rebels which were consistantly put down by the central government.

Modern people tend to think of stage performing as a non-religious practice. But Chinese Opera was performed for the Gods. The statues of Gods were carried out of the temples and set up facing the stage before performances. That's the meaning of Ying shen sai hui, one of the names given to Chinese Opera. In fact, attending the Opera was probably the most widespread collective religious act in China.

People who got part time work as bodyguards had reasons to be great showman. Anything which would spread your reputation or demonstrate your prowess served duel purposes, it could get you new business and it could disuade criminals from challenging you.

The standard way for martial artists to attract new students was to give public performances with acrobatics and other feats of prowess. (What? you knew that?)

So called, "Meditation Sects," often practiced martial arts along with popular ethics (keeping precepts), healing trance (qigong) rituals, and talisman making. Performances of quan (boxing) were often used to recruit new members.

All rebellions in China were religiously inspired to some degree. "Meditation" sects were generally more rebellious than the other popular "Sutra" chanting sects. The lines (or slopes) between illegal and legal were different from village to village, province to province, and year to year, depending on how much civil unrest and civil war there was. [During the 1800's each "Meditation" sect associated itself with a particular trigram from the Bagua, like Kan (water), Li (fire), Xun (wind) etc... The trigram they chose likely represented the category of deity they were devoted to (through sacrifice, invocation, possession, channeling etc...). This practice gives some credence to my theory that Baguazhang was given its name because it emerged from a Daoist lineage which performed secret ceremonies which ritually included all known religious traditions and experiences. Each type of experience was cataloged in the performers body and remembered as belonging to one of the the eight trigrams (bagua). There were many large and small rebellions by these groups, one in the early 1800's was actually called the Bagua Rebellion and had troops separated into trigrams.]

All rebellions in China were religiously inspired to some degree. "Meditation" sects were generally more rebellious than the other popular "Sutra" chanting sects. The lines (or slopes) between illegal and legal were different from village to village, province to province, and year to year, depending on how much civil unrest and civil war there was. [During the 1800's each "Meditation" sect associated itself with a particular trigram from the Bagua, like Kan (water), Li (fire), Xun (wind) etc... The trigram they chose likely represented the category of deity they were devoted to (through sacrifice, invocation, possession, channeling etc...). This practice gives some credence to my theory that Baguazhang was given its name because it emerged from a Daoist lineage which performed secret ceremonies which ritually included all known religious traditions and experiences. Each type of experience was cataloged in the performers body and remembered as belonging to one of the the eight trigrams (bagua). There were many large and small rebellions by these groups, one in the early 1800's was actually called the Bagua Rebellion and had troops separated into trigrams.]In 1728, "...the Yong Zheng Emperor issued the only imperial prohibition of boxing per se that I have seen. He condemned boxing teachers as 'drifters and idlers who refuse to work at their proper occupations,' who gather with their disciples all day, leading to 'gambling, drinking and brawls.'"(Esherick p. 48)

According Avron Albert Boretz’s 1996 dissertation: Martial Gods and Magic Swords: The Ritual Production of Manhood in Taiwanese Popular Religion, the devotees of martial deities in Taiwan train martial arts and are heavily involved with smuggling, drinking and petty crime. So it seems reasonable to assume that some of the boxing teachers the Emperor is condemning are leaders of small religious cults, and some are just Dojo Rats.

Quan, boxing groups which trained in public squares and performed and competed at festivals, were quasi legal because they promoted martial virtue (wude) and actively prepared young men to take the military entrance exam. Boxing groups could be non-religious; However, it is hard to know because they were mainly reported in official documents only when they were part of "meditation" cults. Heterodox religion was more illegal than boxing by itself, even if the sect didn't practice boxing. Still sects were very popular and wide spread.

Most of the time when martial arts are reported in the official histories it is because they were involved in an unorthodox cult. So most of what we know supports the idea that martial arts and religion were intimately connected, we simply don't have much information about non-sectarian martial arts. It is probably true that there were individuals who practiced only forms, applications and sparring like the our modern day stereotypes, but it is very unlikely that "a pure martial arts" lineage or family ever existed. Everybody had a gongfu brother, uncle, or great uncle who crossed over into performance, ritual, religion, banditry or rebellion.

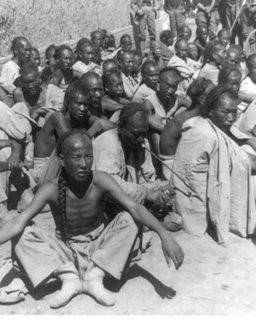

Boxers captured by the Americans

Boxers captured by the AmericansEsherick gives a lot of attention to the overlap between martial conditioning practices like iron t-shirt or golden bell, and invulnerability rituals which incorporate magic, talisman, trance, and possession by local deities and heroic characters from popular opera. There is a continuum from, "Go ahead, hit me, I can take it!" passing through, "Blades always miss me" moving toward, "Due to my amazing qigong, blades can not cut me," and finally ending up with, "Bullets can't harm me, I am a god." Setting aside the question of how well any of these techniques work, it isn't hard to see why 20th Century martial artists, opera performers, religious devotees, and revolutionaries would all want to disassociate themselves from these practices.

In the scramble to invent history, dotted lines have been drawn between "real iron t-shirt" for "real" martial artists, "tricks" used by street performers, "qi illusions" used by magicians and charlatans, and suicidal devotion to a cause--like standing in front of a tank.

It is time to admit that in the 20th Century, embarrassment has been a driving force in the creation and reformulation of martial arts, especial where history is concerned.