Internal martial arts, theatricality, Chinese religion, and The Golden Elixir.

Books: TAI CHI, BAGUAZHANG AND THE GOLDEN ELIXIR, Internal Martial Arts Before the Boxer Uprising. By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($30.00), Digital ($9.99)

Possible Origins, A Cultural History of Chinese Martial Arts, Theater and Religion, (2016) By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($18.95), Digital ($9.99)

Watch Video: A Cultural History of Tai Chi

New Eastover Workshop, in Eastern Massachusetts, Italy, and France are in the works.

Daodejing Online - Learn Daoist Meditation through studying Daoism’s most sacred text Laozi’s Daodejing. You can join from anywhere in the world, $50. Email me if you are interesting in joining!

My Students are Performing April 30th

/Thursday April 30th at 9:50 AM.

The school is called Mission Education Center, use the entrance on the corner of Day Street and Noe Street, in San Francisco's Noe Valley Neighborhood.

Here is a video of students from a previous year at the same school.

Dangerous Women

/ Courtesy of San Francisco Performing Arts Library and Museum

Courtesy of San Francisco Performing Arts Library and Museum Dangerous Women, Warriors, Grannies and Geishas of the Ming, by Victoria Cass came out in 1999, but I just finished reading it. It doesn't have a lot of information about martial arts during the Ming Dynasty but it does a great job of describing what life was like. I highly recommend it.

Cass divides the Ming Dynasty into three realms of action.

The first was the fanatical cult of the family. 40,000 suicidal mothers were officially recognized as martyr goddesses by the Ming governments (1350-1650). Conforming to this cult was a way for women to gain power. I love that she takes the subject most often referred to as "ancestor worship" under a "Confucian" doctrine--and labels it fanatical.

The second realm was Urbanity. China under the Ming Dynasty was the wealthiest country in the world and it had a lavish vibrant urban culture, particularly in the south east. The so called "Education District," was the center of theater and art in every city. Female artists and entertainers of every imaginable sort were not only able to make a living, some got wealthy enough to retire to a country garden with a couple of servants.

The third realm was Solitude. There was the option of being an eccentric outsider. On the one hand there were female bandit leaders who lived in mountain strongholds, Daoist hermits, and hairy recluses who ate only insects. And on the other hand there was an idealized worship of solitude which found expression in private urban retreats, islands of tranquility with perfect artistic wives (Cass uses the Japanese term geisha, the Chinese term is ji, an artist) in grass huts and rock gardens with poetry and exquisite incense. There was a whole milieu of artistically inclined people who competed to see who could be the most reclusive with out leaving the city. Eccentric hermits could tour the urban scene as guests of the well-to-do.

From her description of the three realms, Cass sets off to describe the different types of lives women made from themselves with in those three realms. I was surprised by how common female doctors were. There were also thousands of female spiritual leaders and teachers of every sort. Women could be painters, writers, and actors. There was only one female general, but women were often referred to as "Warrior types." These warrior women for instance would dress up in beautiful armor and tour around the city doing martial performances on horseback. She points out that some of these women were just artists and some were known for sexual prowess. Most no doubt started from desperate circumstances, but Cass points out that most women artists in America have sex with multiple partners too.

The section on Grannies is great too. Older women had hundreds of ways of making independent income; as fortune tellers, as nannies, as sales reps, dealers, matchmaking, connecting people, organizing, curing illness, consoling. They were uniquely un-threatening experts in many realms, especially dark realms, and they had the ability to get intimately close to the workings of everything. Ironically, for this they were also feared! and blamed! The a-moral, strategic, sexual, articulate, trickster granny was among the most popular of literary heroes.

Hey! It's a google book, you can search the whole thing!

Baguazhang's Contentious Beginnings

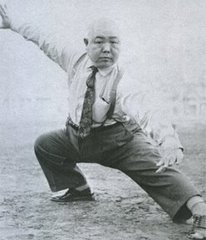

/ Wang Shujin

Wang ShujinKent Howard has translated a book by the famous Baguazhang teacher from Taiwan, Wang Shujin. He has also started a blog to promote it where he has written a number of short essays about the origins of Baguazhang. It is wonderful that someone is taking martial arts history seriously. In the most receint post he takes some time to debunk some of the conjecture out there. Then he says this:

The Story of Dong Haiquan being taught Bagua Zhang as a fully developed martial art by two mountain-dwelling Daoist recluses has all of the basic elements of many a martial art legend in China. All you need to do is change the names, and a few circumstances, and you have Zhang Sanfong creating Taiji Quan from a dream or Shaolin priests learning their art from an Indian monk. Chinese love to shroud their origin myths in the mists of antiquity. It lends them a certain air of distinction and provides an unassailable historical precedent.

There are several elements of this legend, however, that do not stand up well in the face of modern research. First, there has been no discoverable trace in history or literature of two Daoists named, Gu Jici and Shang Daoyuan in the Mount Ermei region of Szechuan Province. Researchers who combed those fabled mountains interviewing present day Daoist adepts found no temple records containing either name, nor of any Daoist recluses of that time who were known to teach martial arts. Second, facts point to Dong learning martial arts in his youth that contained many elements found in modern Bagua Zhang. Third, Dong was a member of the Quan Zhen sect of Daoism and learned a method of walking meditation that resembles Bagua Zhang circle walking patterns and stepping. Finally, Dong Haiquan seemed quite happy to allow the origins of Bagua Zhang to be obscured by legend rather than have contemporaries believe that he had synthesized it whole cloth from elemental skills derived from previous training.

....The last question to take up in our quest for the real Dong Haiquan is whether he popularized an art that had existed previously, or if he invented his own style by marrying disparate methodologies into one cohesive system. This task is made more difficult when you consider that Dong, when asked by his disciples where he learned Bagua Zhang, would comment that he received his art from “a man who lived in the mountains.” If the system existed before Dong Haiquan, we know it was not called Bagua Zhang. That name was unknown before his time. In fact, Dong’s first generation students stated the original name for the system was Zhuan Zhang (Rotating palms). Later it was expanded to Bagua Zhuan Zhang. Finally, probably near the end of Dong’s life, or perhaps even posthumously, it was shorted to Bagua Zhang.

....We can probably never say with absolute certainty if Dong Haiquan learned his art from another source, and merely popularized it, or whether he synthesized techniques learned from several sources and created an entirely new martial system. In any event, Dong was certainly good at marketing his product and keeping the source, as he played his cards, very close to the vest. As Lao Tzu once said, “The Sage wears rough clothing and embraces the jewel within!”

Here is the comment I left on his blog (not approved yet):

Thanks for putting this together.

I would ask the question: What reasons did he have for keeping Baguazhang's origins a secret?

As a marketing strategy it did work, so it is possible that marketing was his reason, but it's not a very good reason considering his main marketing strategy was being the best around. Perhaps his secretiveness was a personality quirk, but that isn't very convincing either. What isn't being said?

- The southern and western half of the country was rebel territory for from 1853-1870. What was he doing during the Taiping rebellion and the many other smaller rebellions during that time?

- What is the evidence that he was a Longmen Daoshi? It is problematic to say that Quanzhen is a "sect," it is a teaching lineage. He could have received "registers," jing (texts), transmissions, etc...from any lineage including Tibetan Banpo--it's all secret under penalty of death. If he had the title Daoshi, then legally speaking he had the rank of an imperial prince. All that stuff about being a eunuch could be discarded that way (see original essay). But the word "Daoshi" could have simply meant magician or wandering recluse.

- For most of the Ching Dynasty and much of the Ming Dynasty as well, Zhengyi Daoism was practiced in secret. It still is. When I visited Chengdu in 2001 I talked to a Chinese Anthropologist who told me that Zhengyi priests managed to hide amongst the poorest villages. He said they have found them, but they disappear by the next day and can not be found again. Daoists often change their names. There is NO reason to believe we could find two "mountain Daoshi" by their names.

- The Quanzhen walking "technique," like everything Quanzhen, is a simplification/purification of older ritual practices. The possibility of Daoist ritual origins for Baguazhang has barely even been scratched.

- Has anyone considered that the name Baguazhang may have been the original name of the art, but it was a secret name, only revealed when the political climate had changed? Rebel-heterodox "meditation" sects often practiced martial arts and named themselves after the trigrams! (See Esherick's "Origins of the Boxer Rebellion.")

- If there ever was anyone else in the early 1800's who practiced this kind of art, perhaps they were in the western part of the country, and perhaps they were wiped out--20 Million people died during the Taiping Rebellion. It kind of makes sense that he wouldn't want to talk about that in Beijing, there were still rebels fighting in 1870 when he started teaching.

Thanks for considering these ideas. ------ The daoist origins of Baguazhang is a repeating theme for me. If readers search the bagua category on the side they'll find a lot of material. People often say that internal martial arts were combined with internal alchemy. Some scholars may argue that ritual, alchemy and martial arts all have separate origins. That may be true, but for the last 2000 years they have been influencing each other. Ritual is the bigger, more encompassing, subject of the three. If you want to understand the origins of martial arts and alchemy, ritual is the place to start.

Dichotomies of Chinese History

/- What is legal vs. what is illegal.

- What was written or talked about vs. what was not written or talked about. (Either secret, implicit, too obvious, or too embarrassing. )

- Official religion vs. Unofficial religion.

- Performance vs. religion.

- Martial arts vs. martial cult.

- Bandit vs. villager.

- Training vs. Organization (spread, hierarchy, transmission).

- Charismatic hierarchies vs. Circles of competing power alliances.

When I studied Budo (sword focused aikido) in Japan at Oomoto, the martial arts training was simply presented as religion. We chanted scripture at the beginning and end of class, we bowed to the spirits in the garden. Oomoto beliefs could be described as traditional animist, post-millennialist, and universalist, but this religion was something we did, not something we believed. Likewise, Religion in China was never something you believed, never. It was always something you did. Often religion could be defined as a group of people you practiced with.

Plum Flower Fist (Quan) for instance, gets its name from the seasonal gatherings in early spring to celebrate the plum blossoms. At these gatherings people would share food, perform their martial arts, have friendly matches, watch musical theater and practice story telling. Here is a quote from The Origins of the Boxer Uprising, by Joseph W. Esherick:

As the conflict escalated in 1897-98, and the pendulum swung from boxer to Christian ascendancy, important changes were occurring in the Plum Flower Boxers. For one thing, Zhao Sanduo was joined by a certain Yao Wenqi, a native of Guangping in Zhili and something of a drifter. He had worked as a potter in a village just west of Linqing, and had taught boxing in the town of Liushangu, southwest of Liyuantun on the Shandong-Zhili border, before moving to Shaliushai where he lived for about a year. Though Yao was apparently senior to Zhao in the Plum Flower school, and thus officially Zhao's "teacher," his influence could not match that of his "student." Yao did, however, serve to radicalize the struggle, and even introduce some new recruits with a reputation for anti-Manchu-ism. This began to bother some of the leaders of the Plum Flower Boxers: "Other teachers often came to urge Zhao not to listen to Yao: 'He is ambitious. Don't make trouble. Since our patriarch began teaching in the late Ming and early Qing there have been sixteen or seventeen generations. The civil adherents read [sacred] books and cure illness, the martial artists practice boxing and strengthening their bodies. None has spoken of causing disturbances.'" For a long time, Zhao seemed inclined to listen to such advice, but as the conflict intensified, he found that he could not extricate himself. In the end the other Plum Flower leaders agreed to let Zhao go his own way--but not in the name of the society. He was, accordingly, forced to adopt a new name for the anti-Christian boxers, the Yihequan [United Righteous Fist, know to history as "The Boxers"].

The Plum Flower School of Boxing (Meihuaquan) always had a civil (wen --as opposed to the wu, martial) component, a wing of the school which read scripture and cured illness using religious means like exorcism and talisman. The concern of the person being quoted in bold lettering above is that the whole organization was rolling down the slope toward illegal, heterodox cult.

The purpose of an organization could be multiple; banditry, rebellion, training, health, crop guarding, military prep-school, village defence, religion, fundraising, alliance building, inter-village conflict, and/or entertainment.

4 stages of Qi

/ George Xu has simplified his explanation of the basic process of making martial arts internal.

George Xu has simplified his explanation of the basic process of making martial arts internal.First there is External-Internal, which means that the jing and qi are mixed. Most martial arts use this method to great effectiveness. It is high quality external martial arts-- muscles, bones and tendons become thick like chocolate.

Second is Internal-External, most advanced taijiquan, xingyiquan, and baguazhang practitioners get stuck here. It means that the body is completely soft and sensitive. While power is constantly available, the yi (mind/intent) is trained to never go against the opponent's force, so that when this kind of practitioner issues power it is in the opponent's most vulnerable place (in friendly practice it is often used to throw the opponent to the ground). Unfortunately, if the opponent gives no opening there is no way to attack. Also, at the moment of attack all jin, no matter how sneaky or subtle, becomes vulnerable to a counter attack.

The third is Pure-Internal, this is very rare. All power is left in a potential state. Because there is no jin, one is not vulnerable to counter attack. To reveal this aspect of a practitioner's true nature requires completely relaxing the physical body so that jing and qi distill from one another. The body becomes like a heavy mass, like a bag of rice, Daoists call it the flesh bag. Then one must go through the four stages of qi:

- Qi must go through the gates. The most common obstacle to this is strength, either physical, psychological, or based in a world-view. After discarding strength the shoulders must be drawn inward until they unify with the dantian. The same is true for the legs; however, the most common obstacle to qi passing freely through the hip gates is too much qi stored in the dantian. Qi must be distributed upwards and released in order for it to descend.

- Qi must conform to the rules of Yin-Yang. As much qi as goes into the limbs must simultaneously go back into the torso.

- The qi must become lively, shrinking expanding and spiraling. (This is what I'm working on.)

- This one in Chinese is Hua--to transform, like ice changing into water and then steam. But George Xu prefers to translate in as melt the qi.

----

Personal Update: I'm going on a classical music only fast.

The Face

/I had no idea there was so much rock and snow on my face, somebody should have said something.

Taiwan Vacation

/As a side note, I'm taking a break from reading the news or blogs that deal with current events. Let's call it a retreat.

I went to see some old Buster Keaton films last night at the Oddball Film Archive. Keaton was the greatest.

The Latest Stuff

/On that note, I wrote about the problem of ergonomic crime here.

It is so windy in San Francisco, I have a wind burn from teaching outside for 5 hours.

My movement, physiology, anatomy and bodywork expert friend Rebbecca has her new website up, it begins modestly with a quote by yours truly.

My honey half-wife acupuncturist now has an interesting and well written blog, Acupuncture Healthcare.

I saw George Xu this weekend. He always says something funny. He told me, "You are like very intelligent furniture." I took his correction and thankfully fixed the problem. He said it with a tone like, 'man.... you are the dumbest of the dumb.' But if you think about it, who would be willing to risk fighting with an intelligent couch? Or an office desk that can kick, or a piano that can jump? He also came up with a great description of what makes internal martial arts unique, "First I throw a 100 pound bag of rice at you, then we fight."

Here is a picture of me teaching some 4th grade students last year.

The Origins of the Boxer Uprising

/ The more I think about it, the more I like Joseph W. Eshrick's The Origins of the Boxing Uprising. He published this book in 1987 (UC Berkeley Press) and the fact that I hadn't read it before now, shows where the holes in my (self) education are. (Please feel free to suggest related books in the comments, even if you think I have read them, I'm sure my readers will be appreciative too.)

The more I think about it, the more I like Joseph W. Eshrick's The Origins of the Boxing Uprising. He published this book in 1987 (UC Berkeley Press) and the fact that I hadn't read it before now, shows where the holes in my (self) education are. (Please feel free to suggest related books in the comments, even if you think I have read them, I'm sure my readers will be appreciative too.)I suspect by now my regular readers join me in being easily offended by the lack of scholarship and basic questioning in the history sections of most martial arts books. While we are justified in finding this failure inexcusable, we must answer this question: Why would 20th Century martial artists deliberately obscure their history?

In the process of explaining the origins of the Boxer Uprising of 1899-1900, Eshrick gives us many clues which will help us understand what martial arts were in the 1800's. Let's first imagine that the same individual people took on at least three of the following if not all of the following roles:

- Performing Chinese Opera

- Practicing Martial Arts

- Devotees of Martial Deities or other heterodox (fanatic) cults

- Bandits (Rarely robbed their own villages, which meant that in places like Western Shandong province people often thought of their neighboring villages as being full of thieves.)

- Officially organized volunteer militias

- Anti-bandit gangs (These were created because official militias couldn't cross provincial boundaries, much like American Sheriffs can't cross state lines.)

- Political Rebels and Revolutionaries

20th Century people who wanted to create revolution, preserve religion, train martial arts, or perform opera, all had incentives to cover up the connectedness of these historic endeavors; to claim they were always separate and to attempt to reform traditional practices so that they would appear to have always been separate.

20th Century people who wanted to create revolution, preserve religion, train martial arts, or perform opera, all had incentives to cover up the connectedness of these historic endeavors; to claim they were always separate and to attempt to reform traditional practices so that they would appear to have always been separate.Everyone wants to say that their system of martial arts was used exclusively by bodyguards. No one wants to say their martial art was developed by a group of Opera performers who practiced in secret over generations in order to train groups of rebels which were consistantly put down by the central government.

Modern people tend to think of stage performing as a non-religious practice. But Chinese Opera was performed for the Gods. The statues of Gods were carried out of the temples and set up facing the stage before performances. That's the meaning of Ying shen sai hui, one of the names given to Chinese Opera. In fact, attending the Opera was probably the most widespread collective religious act in China.

People who got part time work as bodyguards had reasons to be great showman. Anything which would spread your reputation or demonstrate your prowess served duel purposes, it could get you new business and it could disuade criminals from challenging you.

The standard way for martial artists to attract new students was to give public performances with acrobatics and other feats of prowess. (What? you knew that?)

So called, "Meditation Sects," often practiced martial arts along with popular ethics (keeping precepts), healing trance (qigong) rituals, and talisman making. Performances of quan (boxing) were often used to recruit new members.

All rebellions in China were religiously inspired to some degree. "Meditation" sects were generally more rebellious than the other popular "Sutra" chanting sects. The lines (or slopes) between illegal and legal were different from village to village, province to province, and year to year, depending on how much civil unrest and civil war there was. [During the 1800's each "Meditation" sect associated itself with a particular trigram from the Bagua, like Kan (water), Li (fire), Xun (wind) etc... The trigram they chose likely represented the category of deity they were devoted to (through sacrifice, invocation, possession, channeling etc...). This practice gives some credence to my theory that Baguazhang was given its name because it emerged from a Daoist lineage which performed secret ceremonies which ritually included all known religious traditions and experiences. Each type of experience was cataloged in the performers body and remembered as belonging to one of the the eight trigrams (bagua). There were many large and small rebellions by these groups, one in the early 1800's was actually called the Bagua Rebellion and had troops separated into trigrams.]

All rebellions in China were religiously inspired to some degree. "Meditation" sects were generally more rebellious than the other popular "Sutra" chanting sects. The lines (or slopes) between illegal and legal were different from village to village, province to province, and year to year, depending on how much civil unrest and civil war there was. [During the 1800's each "Meditation" sect associated itself with a particular trigram from the Bagua, like Kan (water), Li (fire), Xun (wind) etc... The trigram they chose likely represented the category of deity they were devoted to (through sacrifice, invocation, possession, channeling etc...). This practice gives some credence to my theory that Baguazhang was given its name because it emerged from a Daoist lineage which performed secret ceremonies which ritually included all known religious traditions and experiences. Each type of experience was cataloged in the performers body and remembered as belonging to one of the the eight trigrams (bagua). There were many large and small rebellions by these groups, one in the early 1800's was actually called the Bagua Rebellion and had troops separated into trigrams.]In 1728, "...the Yong Zheng Emperor issued the only imperial prohibition of boxing per se that I have seen. He condemned boxing teachers as 'drifters and idlers who refuse to work at their proper occupations,' who gather with their disciples all day, leading to 'gambling, drinking and brawls.'"(Esherick p. 48)

According Avron Albert Boretz’s 1996 dissertation: Martial Gods and Magic Swords: The Ritual Production of Manhood in Taiwanese Popular Religion, the devotees of martial deities in Taiwan train martial arts and are heavily involved with smuggling, drinking and petty crime. So it seems reasonable to assume that some of the boxing teachers the Emperor is condemning are leaders of small religious cults, and some are just Dojo Rats.

Quan, boxing groups which trained in public squares and performed and competed at festivals, were quasi legal because they promoted martial virtue (wude) and actively prepared young men to take the military entrance exam. Boxing groups could be non-religious; However, it is hard to know because they were mainly reported in official documents only when they were part of "meditation" cults. Heterodox religion was more illegal than boxing by itself, even if the sect didn't practice boxing. Still sects were very popular and wide spread.

Most of the time when martial arts are reported in the official histories it is because they were involved in an unorthodox cult. So most of what we know supports the idea that martial arts and religion were intimately connected, we simply don't have much information about non-sectarian martial arts. It is probably true that there were individuals who practiced only forms, applications and sparring like the our modern day stereotypes, but it is very unlikely that "a pure martial arts" lineage or family ever existed. Everybody had a gongfu brother, uncle, or great uncle who crossed over into performance, ritual, religion, banditry or rebellion.

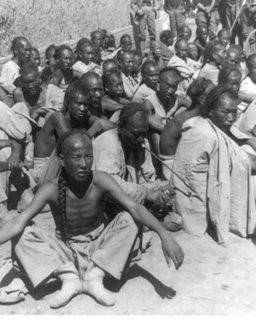

Boxers captured by the Americans

Boxers captured by the AmericansEsherick gives a lot of attention to the overlap between martial conditioning practices like iron t-shirt or golden bell, and invulnerability rituals which incorporate magic, talisman, trance, and possession by local deities and heroic characters from popular opera. There is a continuum from, "Go ahead, hit me, I can take it!" passing through, "Blades always miss me" moving toward, "Due to my amazing qigong, blades can not cut me," and finally ending up with, "Bullets can't harm me, I am a god." Setting aside the question of how well any of these techniques work, it isn't hard to see why 20th Century martial artists, opera performers, religious devotees, and revolutionaries would all want to disassociate themselves from these practices.

In the scramble to invent history, dotted lines have been drawn between "real iron t-shirt" for "real" martial artists, "tricks" used by street performers, "qi illusions" used by magicians and charlatans, and suicidal devotion to a cause--like standing in front of a tank.

It is time to admit that in the 20th Century, embarrassment has been a driving force in the creation and reformulation of martial arts, especial where history is concerned.