Two Talks at Soja Martial Arts

/

Here is the Talk I gave!

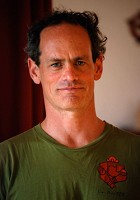

North Star Martial Arts

In depth discussions of internal martial arts, theatricality, and Daoist ritual emptiness. Original martial arts ideas and Daoist education with a sense of humor and intelligence.

Books: TAI CHI, BAGUAZHANG AND THE GOLDEN ELIXIR, Internal Martial Arts Before the Boxer Uprising. By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($30.00), Digital ($9.99)

Possible Origins, A Cultural History of Chinese Martial Arts, Theater and Religion, (2016) By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($18.95), Digital ($9.99)

Watch Video: A Cultural History of Tai Chi

New Eastover Workshop, in Eastern Massachusetts, Italy, and France are in the works.

Daodejing Online - Learn Daoist Meditation through studying Daoism’s most sacred text Laozi’s Daodejing. You can join from anywhere in the world, $50. Email me if you are interesting in joining!

Here is the Talk I gave!

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an inheritance from the ancestors of that art. That practicing a particular tradition is a process of reanimating the movement of the ancestors who created it. I have also written about how practicing a form may correct the errors in the form you inherited, in effect healing those in the past. And I have also written about how practicing a form can heal your parents, your genetic ancestors, through gongfu as a conduct correcting process. Gongfu can be understood as a process of developing efficiency which rectifies the inappropriate, aggressive, and wasteful movement (jing) and breathing (qi) habits which we learned from our parents.

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an inheritance from the ancestors of that art. That practicing a particular tradition is a process of reanimating the movement of the ancestors who created it. I have also written about how practicing a form may correct the errors in the form you inherited, in effect healing those in the past. And I have also written about how practicing a form can heal your parents, your genetic ancestors, through gongfu as a conduct correcting process. Gongfu can be understood as a process of developing efficiency which rectifies the inappropriate, aggressive, and wasteful movement (jing) and breathing (qi) habits which we learned from our parents.Some of the conclusions derived from the serious study of Chinese popular culture in the postwar decades are relevant to our understanding of the embeddedness of Boxer religious experience in... [Northern Chinese] culture. One such conclusion is that, at the village level, the sharp boundaries between the "secular" and the "sacred," to which modern Westerners are accustomed, simply did not exist. The gods of popular religion were everywhere and "ordinary people were in constant contact" with them. These gods were powerful (some, to be sure, more than others), but they were also very close and accessible. People depended on them for protection and assistance in time of need. But when they failed to perform their responsibilities adequately, ordinary human beings could request that they be punished by their superiors. Or they could punish them themselves. "If the god does not show signs of appreciation of the need of rain," Arthur Smith wrote toward the end of the nineteenth century, "he may be taken out into the hot sun and left there to broil, as a hint to wake up and do his duty." This "everydayness" of the gods of Chinese popular religion and the casual, matter-of-fact attitude Chinese typically displayed toward their deities doubtless contributed to the widespread view among Westerners, both in the late imperial period and after, that the Chinese were not an especially religious people. It would be more accurate, I believe to describe the fabric of Chinese social and cultural life as being permeated through and through with religious beliefs and practices.

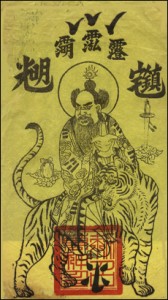

But not always with the same degree of intensity and certainly not with equal discernibleness in all settings. This is another facet of Chinese popular religion that, because it does not entirely square with the expectations of Western observers, has occasioned a certain amount of confusion and perplexity. Sometimes religion appears to recede into the shadows and to be largely, if not altogether, absent from individual Chinese consciousness. But at other times it exercises dominion over virtually everything in sight. Thus, the martial arts, healing practices, and the heroes of popular literature and opera often inhabit a space in Chinese culture that seems unambiguously "secular." But it is not at all unusual, as clearly suggested in the accounts of Boxer spirit possession transcribed at the beginning of this chapter, for these selfsame phenomena to be incorporated into a fully religious framework of meaning.

Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity).

Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity). Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead.

Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead.A place to train and learn about traditional Chinese martial arts, which are a form of religious theater combined with martial skills.