A review of:

History in Three Keys, The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth, by Paul A. Cohen, Columbia University Press, 1997.

So I was doing a little workshop with George Xu last month and he was talking about using Spiritual Fist. Spiritual Fist is what we might call an unconscious level of mastery. Once all the internal and external types of integration, embodiment, differentiation and liveliness are in the right order, they are harmonized by the spirit. That is, we experience the motivation for movement coming from outside the body. This is called Spiritual Fist, or

Shen Quan in Chinese.

So I said, "Shenquan? Isn't that what the Boxers called themselves before the Boxer Rebellion?"

"Yes," said George, "That is what they called themselves. True. But all Chinese arts are called

Shen at the most advanced levels." And then after thinking for a moment (we were practicing some circular explosive movement during this conversation) he said, "The Boxer's problem was that they lacked Harmony. Right?"

Harmony, I thought to myself, what? Then it occurred to me and I said, "That's what they

changed their name to,

Yihequan, literally --One Harmony Fist."

George looked perhaps flustered for a moment, but he quickly dropped the issue and moved on to showing us another inner secret.

It was a stunning reminder that ways of knowing and understanding history often do not transcend culture and language. I have no idea what harmony could mean in that context. (

Yihequan is sometimes translated, Fists United in Righteousness. Did he mean they weren't righteous? enough?)

__________

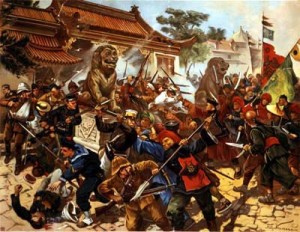

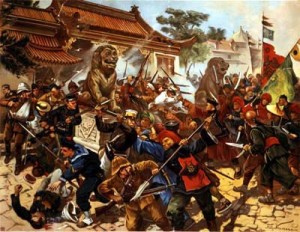

The Boxer Rebellion of 1898-1900 was a bloody uprising in north China against native Christians and foreign missionaries and at times Ching Dynasty Troops. They dressed in Chinese Opera costumes and claimed to be invincible to bullets. Using swords, spears and magic, they took to burning large parts of Beijing, Tianjin and other cities. The boxers were finally put down by foreign troops who took the opportunity to demand concessions and loot the imperial palace.

__________

Paul A. Cohen's book,

History in Three Keys, has a simple enough premise which he uses to divided his book into three parts. The first part is his best shot at what actually happened. The facts and documents sorted in such a way as to give the most likely account of what happened. The second part of the book is an account of what people said and thought about the event at the time. The third part of the book is about how the memory of the events lived on and were manipulated in political debates over the next 80 years.

The first section is only 42 pages long and starts off pointing out that, most people know more details about the Boxer Uprising than they do about the Taiping rebelion, even though the scale of the Taiping Rebelion (20 Million dead over 20 years) dwarfs that of the Boxer Uprising (10's of thousands dead over a year or two), and Taiping was led by a man claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. He then recommends people read

Esherick's Book, The Boxer Uprising, because Esherick did such a good job of showing the local development of the Boxer Movement. But Cohen puts together an excellent summary of the events and adds to Esherick's take details about the wider effects of the event particularly in the far north. He also includes details on the large numbers of Chinese Christians killed by the Boxers. The largest Christian groups in China were, ironically like the Boxers, both anti-foreiner and participants in mass possession rituals.

The second section attempts to delve into the mindset and experiences of the people who participated and witnessed the Boxer Movement. In order to do this,

my regular readers will love this! he dives into studies of African religion. He does this, of course, as a way to gain perspective on Chinese popular religious practices of possession and trance. (

I'm feeling an African Bagua part 3 coming on!)The entire second section is great. He presents an enormous amount of evidence that, although the Boxer Uprising was a unique event, it's defining characteristics were far from rare. Theatrical presentations were the most widespread form of religious activity in China. So called Chinese Opera is a type of martial arts training. Accounts of trance based forms of conditioning against bladed weapons are found through out the Ching Dynasty. Possession rituals were much easier to do and more common in the north than they were in the south (which explains why Taiwan is not a good model for understanding north China).

In chapter 4 titled, Magic and Female Pollution, he explores the boxer beliefs about women and the wider exceptance of those beliefs across northern China. For instance, when boxers actually got shot and died, or when they tried to burn down a single house they said was owned by Christians and it spread to everyone elses house too, they claimed it was because a woman contaminated the scene. (I can see how this kind of thinking gets started, whenever I have trouble finding something like my keys or a book, I right away blame my half-wife. I mean who else could it be, right?)

The book explores how the Boxers' were viewed by other Chinese at the time in many complex and interesting ways. However, it is safe to say that belief in their magical powers and martial prowess was widespread. Ideas which connect religious devotion, theatrical (Opera) characters, magic, and martial arts were not only widely held; they were the stuff daily life was made of.

The Boxers regularly attributed the casualties they suffered in fighting with foreigners in Tianjin to the latter's placement of naked women in the midst or in front of their forces, which broke the power of the Boxers' magic. The story was also circulated and widely believed by the populace that a naked woman straddled each of the many cannon mounted in the foreign buildings in Zizhulin, making it impossible for the "gunfire-repelling magic" (bipao zhi fa) of the Boxers to work properly....

_______________

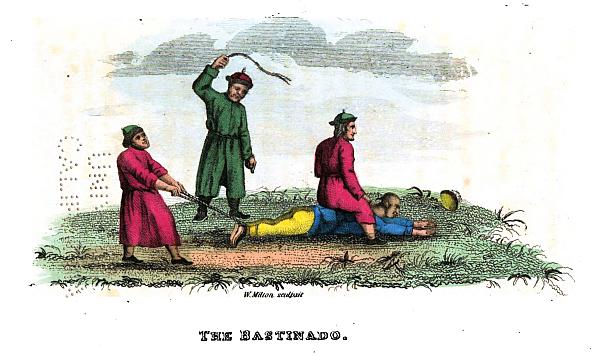

Dirty water, as a dextroyer of magic, was unquestionably related in Boxer minds to the most powerful magic-inhibitor of all: women, and more particularly uncleanness in women, a category that, for the Boxers, included everything from menstrual or fetal blood to nakedness to pubic hair. Water was of course a symbol of yin, the primeval female principle in China, and there was a long-held belief that the symbolic representation of yin could be used to overcome the effects of such phenomena as fire (including gunfire), which was symbolic of the male principle, yang. Several groups of rebels in the late Ming had used women to suppress the firepower of government troops. During the insurgency of 1774 in Shandong, Wang Lun's forces used and array of magical techniques, including strange incantations and women soldiers waving white fans, in their assault on Linqing. the imperial defenders of the city were at first frustrated by the effectiveness of the rebels' fighting tactics. An old soldier, however, came to the rescue with this advice: "Let a prostitute go up on the wall and take off her underclothing...we will use yin power to counter their spells." When this proposal was carried out and proved effective, the government side adopted additional measures of a like sort, including, as later recounted by Wang Lun himself, "women wearing red clothing but naked from the waist down, bleeding and urinating in order to destroy our power."

Such magic-destroying strategies were clearly well established in Chinese minds. The nurse who took care of the famous writer Lu Xun when he was a little boy once told him the following story about her experience with the Taiping rebels: "When gorvernment troops came to attack the city, the Long Hairs [the Taiping] would make us take off our trousers and stand in a line on the city wall, for then the army's cannon could not be fired. If they fired then, the cannon would burst!"

Paul A. Cohen does not appear to be a martial artist or a person with a performing background, so he doesn't go into depth with either of these. However, he makes it clear that martial arts and theater were always part of the mix.

Here is an excerpt from an article about a famous martial artist whose martial arts family were leaders of the Boxers. That means that in addition to being Traditional Chinese Medical Doctors, bodyguards and caravan guards, they performed magical spells to protect themselves while killing Chinese Christians, while dressed in Chinese Opera costumes, possessed by hero-gods of the theater.

Pei Xirong was born in 1913 in Raoyang county in Hebei province. His father was a core member of the Yi He Tuan [the Boxers], and his mother had also participated in the ‘Red Lantern’ movement [the female part of the Boxers movement, dealt with extensively in Cohen's book]. His uncle, Qi Dalong, was a bodyguard in the caravan agency established by Li Cunyi who guarded caravans traveling between Tianjin and Gubeikou. When the Allied Forces invaded Tianjin, he and Li Cunyi battled against the invaders at Laolongtou Train Station. He fought courageously, sustaining several wounds.

The third part of Cohen's book is also good. (

I quoted from it twice in my review of Rovere's book about xingyi in the Chinese army.) It deals extensively with the process of internalization and self-torturous humiliation that came to produce the modern ideas about pure Martial Arts and the guoshu movement (national arts).

One reason this is personal to me is that in the period directly after the Boxer Uprising, my first teacher's teacher, Kuo Lien-ying studied and performed the roll of monkey in Chinese Opera as a teen-ager. The character/god of monkey was one of the most common gods to possess the Boxers during battle. Kuo also competed in Leitai fights (staged on a platfrom), he could still sing Opera parts 70 years later, and he was still doing drunken monkey gongfu too. Kuo was part of the pure martial arts movement, and guoshu, and an early student of

Wang Xiangzhai. He worked as a bodyguard too. And he could tie a rope dart around his chest under his coat and shake in such a way that the dart would fly out and stick into a tree. And he could tie up any of his actively resisting students with the same technique. None of his students learned the rope dart. And the one student who learned drunken monkey no longer practices. I think we owe it to the last generation, who brought these fantastic arts to us, to try an recover as much of the full picture as we can.

The last section of Cohen's book deals with the Cultural Revolution. It has a few interesting facts. Probably the most prominent cultural reference to the Boxers during that time, a time when George Xu was fighting in the streets on a daily basis, was a play called

Shen Quan, Spiritual Fist.

If we are ever going to have a chance of understanding what the origins of Chinese Martial arts are, we are going to have to drop the stories of purely rational martial tough guys. There is still so much that can be recovered from these arts, because they were designed as storehouses of knowlege. Perhaps, once upon a time, there were legitmate arguments for dicarding central aspects of the tradition, but now, that time has passed. Nobody believes anymore that womens' underpants can protect them from bullets. It's time to see the whole thing for what it is and what is was---a deeply religious, theatrical, health sustaining, fighting arts tradition.

Elaine Scarry's book On Beauty and Being Just begins by explaining that there are two types of mistakes we make about beauty. The first is the mistake of thinking something is not beautiful and later realizing that it is. The second mistake is thinking something is beautiful and later realizing that we've been duped. She then goes on to argue that it is our experience of these two types of mistakes which gives us our sense of justice. It's a sweet argument. (I'll come back to this.)

Elaine Scarry's book On Beauty and Being Just begins by explaining that there are two types of mistakes we make about beauty. The first is the mistake of thinking something is not beautiful and later realizing that it is. The second mistake is thinking something is beautiful and later realizing that we've been duped. She then goes on to argue that it is our experience of these two types of mistakes which gives us our sense of justice. It's a sweet argument. (I'll come back to this.)

Jason Couch of Martial History Magazine sent me this article he put together

Jason Couch of Martial History Magazine sent me this article he put together  gfu on the brain.” It’s a possibility, I admit. Sometimes I get excited and I start to see martial arts in everything (Richard Rorty would call it the narcissistic tendency of powerful ideas). I can use Kungfu power to scrub the dishes. I can use maximum muscle tendon twisting to wring-out the laundry. I can set the table “the way a beautiful woman would do it,” (that’s an alternate name for Baguazhang seventh palm change).

gfu on the brain.” It’s a possibility, I admit. Sometimes I get excited and I start to see martial arts in everything (Richard Rorty would call it the narcissistic tendency of powerful ideas). I can use Kungfu power to scrub the dishes. I can use maximum muscle tendon twisting to wring-out the laundry. I can set the table “the way a beautiful woman would do it,” (that’s an alternate name for Baguazhang seventh palm change). I’ve had a taste of several different styles of African and African Diaspora Dances but my actual training was in Congolese and African-Haitian Dance. My Congolese Dance teacher, Malonga Casquelourd, learned to dance from soldiers on army bases.

I’ve had a taste of several different styles of African and African Diaspora Dances but my actual training was in Congolese and African-Haitian Dance. My Congolese Dance teacher, Malonga Casquelourd, learned to dance from soldiers on army bases.

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background.

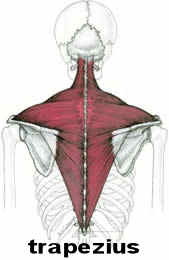

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background. Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.)

Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.) The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.

The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles. A review of:

A review of:  The first section is only 42 pages long and starts off pointing out that, most people know more details about the Boxer Uprising than they do about the Taiping rebelion, even though the scale of the Taiping Rebelion (20 Million dead over 20 years) dwarfs that of the Boxer Uprising (10's of thousands dead over a year or two), and Taiping was led by a man claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. He then recommends people read

The first section is only 42 pages long and starts off pointing out that, most people know more details about the Boxer Uprising than they do about the Taiping rebelion, even though the scale of the Taiping Rebelion (20 Million dead over 20 years) dwarfs that of the Boxer Uprising (10's of thousands dead over a year or two), and Taiping was led by a man claiming to be the brother of Jesus Christ. He then recommends people read  Paul A. Cohen does not appear to be a martial artist or a person with a performing background, so he doesn't go into depth with either of these. However, he makes it clear that martial arts and theater were always part of the mix.

Paul A. Cohen does not appear to be a martial artist or a person with a performing background, so he doesn't go into depth with either of these. However, he makes it clear that martial arts and theater were always part of the mix.