Internal martial arts, theatricality, Chinese religion, and The Golden Elixir.

Books: TAI CHI, BAGUAZHANG AND THE GOLDEN ELIXIR, Internal Martial Arts Before the Boxer Uprising. By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($30.00), Digital ($9.99)

Possible Origins, A Cultural History of Chinese Martial Arts, Theater and Religion, (2016) By Scott Park Phillips. Paper ($18.95), Digital ($9.99)

Watch Video: A Cultural History of Tai Chi

New Eastover Workshop, in Eastern Massachusetts, Italy, and France are in the works.

Daodejing Online - Learn Daoist Meditation through studying Daoism’s most sacred text Laozi’s Daodejing. You can join from anywhere in the world, $50. Email me if you are interesting in joining!

Fruition

/Pure Internal Power

/The first part is an attack on application demo's we see all the time on Youtube-- without shaking power most of them are useless.

The second part is a challenge to all the people who make a distinction between long power and short power. The issue came up in Taiwan talking to Marcus Brinkman and Formosa Neijia, and it is in Nam Park's bagua books too. It's a pretty common way of talking about internal power. The distinction between long power and short power certainly is effective for fighting, there is no conflict here. My challenge is for them to explain how they can do it without creating an on-off switch in their power. I argue that short power needs a root and is thus vulnerable to uprooting. In short, the theory of long and short power does not conform to the Internal Classics idea that, "I know you, but you don't know me."

In putting out this challenge it is my hope that I can learn more about my own limitations, no doubt they are legion. Let the sparks fly.

Taiwan Project

/I went on a reading frenzy in the two months before I came and it has continued since I arrived. On Friday I met with professor Paul Katz in his office at the Academia Sinica and he gave me three papers to read and made a number of further suggestions for future reading. Two of the papers were on the organization of martial cults, dance procession groups dedicated to martial deities and exorcistic rites. The third paper was on the roll of justice and judicial thinking in Daoist ritual and its relationship to a wide range of social institutions including martial cults. He has been very helpful in introducing me to other scholars here too. Our talk was less than an hour but it gave me a lot to think about and helped me organize my ideas from the point of view of a research project which is turning out to be essential for speaking with other scholars.

The next day I met with Dave Chesser of the blog Formosa Neijia. We had a wide ranging talk about life in Taiwan, martial arts gossip, and business. As readers of his blog know, he has a real talent for encouraging friendly open debate and we talked about how he can use that skill and experience to build a school integrating kettle ball training and martial arts skills. He has read all my father’s books on business so we really got into how to translate my father’s ideas about what makes a business flourish into the Taiwanese context. As all business people know, being in business means constantly refining and adapting what you do through trial and error. And that takes time. In my opinion he has what it takes to be successful and he’s off to a good start.

Dave convinced me to take a class with He Jing-Han (his blog is: http://tw.myblog.yahoo.com/hejinghan-bagua). Master He taught a three hour class in the park behind the big public library (where students on the weekend line up 2 hours before opening time, just to make sure they have an air conditioned place to study). The class was focused on a linear form of baguazhang he calls baguaquan, the form can be seen on his Youtube channel. This form is just a small part of what he teaches year round and I got the impression that his style of baguazhang is organized very differently than mine. In fact, of all the things I’ve studied it most resembled the mixed internal/external Lanshou system I originally learned from George Xu 20 years ago. I would love to come back and get a sense of the full scope of what he teaches, this guy is a living treasure.

Shirfu He is a warm and gracious guy. After class we went to lunch for two hours and had a wonderful talk about Daoism and the history of internal martial arts. When I told him about my project He suggested that martial cults were created for group fighting while martial arts are focused on individual fighting, but he conceded that it was quite possible that historically people practiced and taught both together. He also made the important point that what he teaches has changed dramatically from what his teacher, born in 1906, taught. He suggested it was nearly possible to comprehend how his teacher thought about the arts, considering he lived through such different and turbulent times. Going back 5 or 6 generations is really stretching credulity. I know he is right and yet the project seems important anyway. I think it is worth while trying to understand not only what teachings have been discarded or changed, but why.

I also had the opportunity to meet twice with Marcus Brinkman. Once for a Chinese Medical Cupping treatment (my whole back got cupped with more suction than I’ve felt before!) and once for a Baguazhang lesson on his roof. He is a fun guy with an in depth knowledge of Chinese medicine and substantial martial prowess. He gave me some really good theoretical explanations about the relationship of internal martial arts and medicine, but I’ll save them for some future blogs. (I need time to digest them!)

Yesterday I met with a Professor of Daoism named Hsieh Shi-Wei. I honestly believe he is the first person to really understand the full scope of my project and he was very encouraging! More on that later.

Other highlights--

People are warm, kind and helpful. The subway and bus system in Taipei works like a charm. I don’t even have to pull my pass out of my wallet because it has a radio chip in it, I don’t even have to slow my stride when entering and exiting the subway! Taipei is much cleaner than I imagined it would be, public bathrooms are much cleaner here than they are in America. I went drinking at an outdoor beer factory and a dinosaur bone covered bar. I’ve enjoyed asparagus juice, salt-coffee, a mug-bean smoothie, tons of interesting street food, seaweed chips, a harrowing scooter ride, and I stubbed my middle toe black and blue hiking in the mountains.

I have one more meeting here in Taipei tomorrow and then I think I’m headed for the south.

Real Lineages

/Still, in both eras movement artists desired to have the authority of some all powerful "science" on their side; a desire which seems absurd now, in a time when no one is contesting my right or my duty to practice and teach gongfu. Politics is not a rational process. Lineages are a political tool, not a rational one, and certainly not scientific.

Perhaps I accidentally implied that no lineages are real. Shaman, Wu, Tangki, magicians, even puppeteers pick disciples to whom they give the responsibility of passing on a classical art or ritual tradition. In India, Japan and China the disciple is often a family member, but if the extended family hasn't produced any suitable offspring, a disciple will be adopted.

The more illegal (remember legal/illegal is a continum in China) an art is, the more likely it is to be secretive. Also, magicians, martial arts and ritual experts usually had good reasons to keep trade secrets close to their chests. Lineages served this political purpose well. The early 20th century ridiculed secretive behavior none the less, and people at least pretended that all their secrets had been revealed. (I believe Cheng Man Ch'ing wrote a book on Tai Chi book called, "There Are No Secrets.")

I don't believe there are real historical martial arts lineages which were devoid of performance, ritual, religion, or rebellion. But lineage, by its nature, is a changing thing and could certainly purge itself of these aspects and remain a lineage. But be suspicious, a martial art that has had a lot of purging will also have a lot of inexplicable baggage. It's a lot easier to assess the value of an art when you have the whole thing intact, and NOBODY seems to have that!

I suspect there was some previous era where martial arts were shared freely. Buddhist temples had open courtyards where locals could get together and practice. Villages had clan halls where people could get together and practice. I think there was always some paranoia, but it may have been more like basketball secrets. Every village and every temple sponsored a team, and everyone wanted the quality of their competing teams to be high--so after dominating for a few seasons-- you traded coaches.

I'm optimistic that the commercial world is leading us into an era of great sharing.

If there was a "how to" martial arts literature prior to the Ching Dynasty, it seems lost to us now. Martial arts have come down to us primarily as the arts of the illiterate. I do believe at one time martial arts were "high-culture." The evidence for that is in the philosophical literature of the Waring States Era. It is entirely possible that the Tang and Song Era had these too, but perhaps they were destroyed during the years of Mongol rule.

The other group of people who have lineages are Daoist Priests, Daoshi. Daoism is a lineage tradition, everyone given the title Daoshi was included in a lineage and each individual teaching or text had its own lineage. In the event that someone set off on their own and created some new supportive practice or teaching, after a generation or so it/they would be incorporated/adopted into existing lineages. Scholars have their doubts about just how far back some of these lineages go, but no one doubts that they do go way back. But it is also true that most of these lineages are secret. The ones we know about are the ones that stopped being secret to some extent. I suspect that martial artists, beginning in the Ching Dynasty, started imitating Daoist (and Buddhist) ideas of lineages. Martial arts may not have had lineages before that.

Then again their may have been secret Daoist lineages of martial arts. As Shahar points out in his book Shaolin Temple, the popular literature of the Yuan and Ming Dynasties grew out of theater and is perpetually making fun of Daoists, Buddhist, officials, and martial heroes (xia) with their secret techniques.

I've been looking through the index to the Ming Dynasty Daoist Cannon (Daozang) which was just published last year. There are a lot of texts which describe physical practices in conjunction with ritual, purification, astrology, meditation etc... There may even be a few texts which are primarily movement oriented (requiring lineage transmission, of course), but I see nothing resembling martial arts. If such texts ever existed they are either still hidden, or they were destroyed 900 years ago a long with thousands of other texts during the Yuan Dynasty.

Marrow of the Nation

/ I just finished reading Andrew D. Morris, Marrow of the Nation, A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China, UC Press 2004.

I just finished reading Andrew D. Morris, Marrow of the Nation, A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China, UC Press 2004.Before I tell you about that I just want to say I've got a lot on my plate before I leave for Taiwan and so I apologize if my blogging seems rushed and...

My advanced students from ER Taylor Elementary School are performing again, Saturday May 16th, this time at San Francisco's beautiful new De Young Museum. They'll be on the Outdoor Cafe Stage at 1:45 PM, it's free.

Marrow of the Nation contributes an important piece of history to our understanding of why Chinese Martial Arts History is such a madhouse of unsupportable fiction (and also why, as Chris at Martial Development pointed out, some comic fictional films are closer to the truth than the books historians have written).

In the early 20th Century Chinese people, particularly urban people, were deeply humiliated. For 300 years they had been under foreign Manchu rulers, forced to wear their hair in a queue as symbolic slaves. The Chinese people saw themselves as collaborators in their own oppression. They were unable to work together to overthrow a weak corrupt government until a group of 9 foreign powers allied to bring China to it's knees. All the foreign powers were Christian, except Japan, and all were promoters of Modernity.

Scientism, Rationalist extremism, absolutist truths, and the relentless quests for purity of form, and transparent clarity--swept the country like wild fire. China turned on itself. Anything old which required oral transmission, anything mysterious, secret, difficult to learn, or regionally particular, was viciously attacked as the cause of China's past failures and humiliations. Thus it was claimed, Martial arts were practiced by dirty herbalists, religious nuts, and desperate performers who gather up ignorant crowds and block traffic.

Martial Arts were to be replaced by tiyu, Physical Culture. By that they meant Western Sports fitness and Olympic style competitions. Physical Education Departments opened up in schools all over the country.

Huges swaths of Martial Arts culture were wiped out, never to be seen again. Imagine having spent your life developing an extraordinary "spirit fist" only to be surrounded by ridicule on a national scale. Most chose to take their secrets with them to their graves, many probably committed suicide.

Those martial artist activists who resisted the onslaught of hysteria did so in the name of Modernity! The first powerful voice for making Kungfu part of Modernity was called The Pure Martial Society (Jingwu Hui). They argued that martial arts could be a sport like any other sport. All the other sports came from the West, having a Sport with Chinese roots would be a great source of pride which would help build the nation. For Kungfu to be a sport it had to be totally open, accessible to women, have a clear standard curriculum, have a health and fitness component free of terms like jing, qi or shen, and be competition oriented. Jingwu swept the country and Chinese communities in South East Asia. As political fortunes changed it was surpassed by the Guoshu (National Art) movement. The Kuomintang Government of Chang Kai-Shek (he was a Methodist Christian) implemented Guoshu schools all over the country, at least where he was in power, and used the competitions along with academic testing to pick officers in his government and armies. But everybody who taught martial arts started calling it Guoshu, meaning that they agreed with the modernizing, scienticization project.

They tended to argue that in the past there was a pure fighting art that had been corrupted and could now be extricated from the mildew of history by being simplified and mixed with fitness training. But there were lots of arguments. Some argued that martial virtues had been lost. This was the period when people started making up lineages and publishing teaching manuals.

The lineages allowed people to pretend they came from a great and pure martial line of masters dedicated to nothing but martial virtue and pure technique. Inventing the lineages allowed people to write religion, rebellion and performance out of history. Some of the lineages may have been real, but they were not pure. By claiming a lineage people were also renouncing the past, both real and imagined, they were saying in effect, 'Now THIS art, which was unfortunately secret for many generations is now totally clear and open! Anyone with four limbs and two ears can learn it!'

There was a guy named Chu Minyi who served as a minister for the Kuomintang. He invented something called Taijicao (Tai Chi Calisthenics) and in 1933 wrote a book called Tai Chi Calisthenics Instructions and Commands. "Whereas traditional tai chi was simply too difficult for any but the most dedicated martial artist to master, tai chi calisthenics were pleasingly easy to learn and practice." They could be done in a few minutes and they used a counting formula like jumping jacks. He also gets credit in the book for inventing the Tai Chi Ball practices. (Hey, I didn't write the book, but those tai chi ball exercises always looked a little too much like rhythmic gymnastics for my taste.)

Chu's Tai Chi Calisthenics were performed on stage at the 1936 Olympics. Fortunately or unfortunately he was a peace activist and so naturally supported the Japanese when they invaded and was later executed for treason. But not before performing one last taijquan set in front of the firing squad.

Check out the book. All the good stuff is in Chapter 7, "From Martial Arts to National Skills."

This is all great background for understanding Wang Xiangzai's challenge to every martial artist in the country to either fight him or sit down and explain their art in plain language. It explains why he wanted to to throw out forms, shaolin, performance, philosophy, theory, religion, etc... It also helps explain why his students were confused enough to go in three different directions; 1) standing still as a pure health practice, 2) fighting is everything, and 3) knocking people over by blasting them with qi from a distance.

(hat tip to: Daniel)

UPDATE: Here is a video of Chu Minyi! Yeah!

Haramaki

/ Haramaki

Haramaki I've been wearing a haramaki everyday for two months. The fashionistas among my readers already know that this ancient Samurai undergarment is fast becoming a must have. Here is the Wiki page.

I've been wearing a haramaki everyday for two months. The fashionistas among my readers already know that this ancient Samurai undergarment is fast becoming a must have. Here is the Wiki page.I can think of no other article of clothing more likely to improve your gongfu than a haramaki. They help you establish a "frame" and relax the dantian. My advice, toss in the towel with all that core strengthening gobbly gook and just get yourself a haramaki!

I have one wool and two stretch cotton haramakis. This is the type I have, (Item No. mn-1002, mn-1003) scroll down...find the products second from the bottom!

You can read more about fashion and health benefits here, and here, and then there is Haramaki Love.

I

n China the generals used to wear a very heavy tiger skin attached where the haramaki is

n China the generals used to wear a very heavy tiger skin attached where the haramaki is , it would hang down to their knees and probably felt something like an x-ray apron. A softer lighter version was worn by children and used by women for the month after pregnancy, when they were most vulnerable to spirit invasion. The tangki, or spirit mediums of Singapore and other places where Hokkien culture is strong, wear this kind of bib (tou-ioe) when they are possessed by war gods and when they are possessed by baby or child gods. The tiger skin is worn ritually in Tibet and of course Shiva wears one too.

, it would hang down to their knees and probably felt something like an x-ray apron. A softer lighter version was worn by children and used by women for the month after pregnancy, when they were most vulnerable to spirit invasion. The tangki, or spirit mediums of Singapore and other places where Hokkien culture is strong, wear this kind of bib (tou-ioe) when they are possessed by war gods and when they are possessed by baby or child gods. The tiger skin is worn ritually in Tibet and of course Shiva wears one too.For internal martial artists the image of the heavy tiger skin apron is a reminder to first let the muscle mass of the lower body hang heavily before the mind moves the qi (and the mass follows the qi, of course).

Tibetan Ritual Tiger

Tibetan Ritual Tiger Red Haramaki

Red HaramakiDichotomies of Chinese History

/- What is legal vs. what is illegal.

- What was written or talked about vs. what was not written or talked about. (Either secret, implicit, too obvious, or too embarrassing. )

- Official religion vs. Unofficial religion.

- Performance vs. religion.

- Martial arts vs. martial cult.

- Bandit vs. villager.

- Training vs. Organization (spread, hierarchy, transmission).

- Charismatic hierarchies vs. Circles of competing power alliances.

When I studied Budo (sword focused aikido) in Japan at Oomoto, the martial arts training was simply presented as religion. We chanted scripture at the beginning and end of class, we bowed to the spirits in the garden. Oomoto beliefs could be described as traditional animist, post-millennialist, and universalist, but this religion was something we did, not something we believed. Likewise, Religion in China was never something you believed, never. It was always something you did. Often religion could be defined as a group of people you practiced with.

Plum Flower Fist (Quan) for instance, gets its name from the seasonal gatherings in early spring to celebrate the plum blossoms. At these gatherings people would share food, perform their martial arts, have friendly matches, watch musical theater and practice story telling. Here is a quote from The Origins of the Boxer Uprising, by Joseph W. Esherick:

As the conflict escalated in 1897-98, and the pendulum swung from boxer to Christian ascendancy, important changes were occurring in the Plum Flower Boxers. For one thing, Zhao Sanduo was joined by a certain Yao Wenqi, a native of Guangping in Zhili and something of a drifter. He had worked as a potter in a village just west of Linqing, and had taught boxing in the town of Liushangu, southwest of Liyuantun on the Shandong-Zhili border, before moving to Shaliushai where he lived for about a year. Though Yao was apparently senior to Zhao in the Plum Flower school, and thus officially Zhao's "teacher," his influence could not match that of his "student." Yao did, however, serve to radicalize the struggle, and even introduce some new recruits with a reputation for anti-Manchu-ism. This began to bother some of the leaders of the Plum Flower Boxers: "Other teachers often came to urge Zhao not to listen to Yao: 'He is ambitious. Don't make trouble. Since our patriarch began teaching in the late Ming and early Qing there have been sixteen or seventeen generations. The civil adherents read [sacred] books and cure illness, the martial artists practice boxing and strengthening their bodies. None has spoken of causing disturbances.'" For a long time, Zhao seemed inclined to listen to such advice, but as the conflict intensified, he found that he could not extricate himself. In the end the other Plum Flower leaders agreed to let Zhao go his own way--but not in the name of the society. He was, accordingly, forced to adopt a new name for the anti-Christian boxers, the Yihequan [United Righteous Fist, know to history as "The Boxers"].

The Plum Flower School of Boxing (Meihuaquan) always had a civil (wen --as opposed to the wu, martial) component, a wing of the school which read scripture and cured illness using religious means like exorcism and talisman. The concern of the person being quoted in bold lettering above is that the whole organization was rolling down the slope toward illegal, heterodox cult.

The purpose of an organization could be multiple; banditry, rebellion, training, health, crop guarding, military prep-school, village defence, religion, fundraising, alliance building, inter-village conflict, and/or entertainment.

4 stages of Qi

/ George Xu has simplified his explanation of the basic process of making martial arts internal.

George Xu has simplified his explanation of the basic process of making martial arts internal.First there is External-Internal, which means that the jing and qi are mixed. Most martial arts use this method to great effectiveness. It is high quality external martial arts-- muscles, bones and tendons become thick like chocolate.

Second is Internal-External, most advanced taijiquan, xingyiquan, and baguazhang practitioners get stuck here. It means that the body is completely soft and sensitive. While power is constantly available, the yi (mind/intent) is trained to never go against the opponent's force, so that when this kind of practitioner issues power it is in the opponent's most vulnerable place (in friendly practice it is often used to throw the opponent to the ground). Unfortunately, if the opponent gives no opening there is no way to attack. Also, at the moment of attack all jin, no matter how sneaky or subtle, becomes vulnerable to a counter attack.

The third is Pure-Internal, this is very rare. All power is left in a potential state. Because there is no jin, one is not vulnerable to counter attack. To reveal this aspect of a practitioner's true nature requires completely relaxing the physical body so that jing and qi distill from one another. The body becomes like a heavy mass, like a bag of rice, Daoists call it the flesh bag. Then one must go through the four stages of qi:

- Qi must go through the gates. The most common obstacle to this is strength, either physical, psychological, or based in a world-view. After discarding strength the shoulders must be drawn inward until they unify with the dantian. The same is true for the legs; however, the most common obstacle to qi passing freely through the hip gates is too much qi stored in the dantian. Qi must be distributed upwards and released in order for it to descend.

- Qi must conform to the rules of Yin-Yang. As much qi as goes into the limbs must simultaneously go back into the torso.

- The qi must become lively, shrinking expanding and spiraling. (This is what I'm working on.)

- This one in Chinese is Hua--to transform, like ice changing into water and then steam. But George Xu prefers to translate in as melt the qi.

----

Personal Update: I'm going on a classical music only fast.

The Origins of the Boxer Uprising

/ The more I think about it, the more I like Joseph W. Eshrick's The Origins of the Boxing Uprising. He published this book in 1987 (UC Berkeley Press) and the fact that I hadn't read it before now, shows where the holes in my (self) education are. (Please feel free to suggest related books in the comments, even if you think I have read them, I'm sure my readers will be appreciative too.)

The more I think about it, the more I like Joseph W. Eshrick's The Origins of the Boxing Uprising. He published this book in 1987 (UC Berkeley Press) and the fact that I hadn't read it before now, shows where the holes in my (self) education are. (Please feel free to suggest related books in the comments, even if you think I have read them, I'm sure my readers will be appreciative too.)I suspect by now my regular readers join me in being easily offended by the lack of scholarship and basic questioning in the history sections of most martial arts books. While we are justified in finding this failure inexcusable, we must answer this question: Why would 20th Century martial artists deliberately obscure their history?

In the process of explaining the origins of the Boxer Uprising of 1899-1900, Eshrick gives us many clues which will help us understand what martial arts were in the 1800's. Let's first imagine that the same individual people took on at least three of the following if not all of the following roles:

- Performing Chinese Opera

- Practicing Martial Arts

- Devotees of Martial Deities or other heterodox (fanatic) cults

- Bandits (Rarely robbed their own villages, which meant that in places like Western Shandong province people often thought of their neighboring villages as being full of thieves.)

- Officially organized volunteer militias

- Anti-bandit gangs (These were created because official militias couldn't cross provincial boundaries, much like American Sheriffs can't cross state lines.)

- Political Rebels and Revolutionaries

20th Century people who wanted to create revolution, preserve religion, train martial arts, or perform opera, all had incentives to cover up the connectedness of these historic endeavors; to claim they were always separate and to attempt to reform traditional practices so that they would appear to have always been separate.

20th Century people who wanted to create revolution, preserve religion, train martial arts, or perform opera, all had incentives to cover up the connectedness of these historic endeavors; to claim they were always separate and to attempt to reform traditional practices so that they would appear to have always been separate.Everyone wants to say that their system of martial arts was used exclusively by bodyguards. No one wants to say their martial art was developed by a group of Opera performers who practiced in secret over generations in order to train groups of rebels which were consistantly put down by the central government.

Modern people tend to think of stage performing as a non-religious practice. But Chinese Opera was performed for the Gods. The statues of Gods were carried out of the temples and set up facing the stage before performances. That's the meaning of Ying shen sai hui, one of the names given to Chinese Opera. In fact, attending the Opera was probably the most widespread collective religious act in China.

People who got part time work as bodyguards had reasons to be great showman. Anything which would spread your reputation or demonstrate your prowess served duel purposes, it could get you new business and it could disuade criminals from challenging you.

The standard way for martial artists to attract new students was to give public performances with acrobatics and other feats of prowess. (What? you knew that?)

So called, "Meditation Sects," often practiced martial arts along with popular ethics (keeping precepts), healing trance (qigong) rituals, and talisman making. Performances of quan (boxing) were often used to recruit new members.

All rebellions in China were religiously inspired to some degree. "Meditation" sects were generally more rebellious than the other popular "Sutra" chanting sects. The lines (or slopes) between illegal and legal were different from village to village, province to province, and year to year, depending on how much civil unrest and civil war there was. [During the 1800's each "Meditation" sect associated itself with a particular trigram from the Bagua, like Kan (water), Li (fire), Xun (wind) etc... The trigram they chose likely represented the category of deity they were devoted to (through sacrifice, invocation, possession, channeling etc...). This practice gives some credence to my theory that Baguazhang was given its name because it emerged from a Daoist lineage which performed secret ceremonies which ritually included all known religious traditions and experiences. Each type of experience was cataloged in the performers body and remembered as belonging to one of the the eight trigrams (bagua). There were many large and small rebellions by these groups, one in the early 1800's was actually called the Bagua Rebellion and had troops separated into trigrams.]

All rebellions in China were religiously inspired to some degree. "Meditation" sects were generally more rebellious than the other popular "Sutra" chanting sects. The lines (or slopes) between illegal and legal were different from village to village, province to province, and year to year, depending on how much civil unrest and civil war there was. [During the 1800's each "Meditation" sect associated itself with a particular trigram from the Bagua, like Kan (water), Li (fire), Xun (wind) etc... The trigram they chose likely represented the category of deity they were devoted to (through sacrifice, invocation, possession, channeling etc...). This practice gives some credence to my theory that Baguazhang was given its name because it emerged from a Daoist lineage which performed secret ceremonies which ritually included all known religious traditions and experiences. Each type of experience was cataloged in the performers body and remembered as belonging to one of the the eight trigrams (bagua). There were many large and small rebellions by these groups, one in the early 1800's was actually called the Bagua Rebellion and had troops separated into trigrams.]In 1728, "...the Yong Zheng Emperor issued the only imperial prohibition of boxing per se that I have seen. He condemned boxing teachers as 'drifters and idlers who refuse to work at their proper occupations,' who gather with their disciples all day, leading to 'gambling, drinking and brawls.'"(Esherick p. 48)

According Avron Albert Boretz’s 1996 dissertation: Martial Gods and Magic Swords: The Ritual Production of Manhood in Taiwanese Popular Religion, the devotees of martial deities in Taiwan train martial arts and are heavily involved with smuggling, drinking and petty crime. So it seems reasonable to assume that some of the boxing teachers the Emperor is condemning are leaders of small religious cults, and some are just Dojo Rats.

Quan, boxing groups which trained in public squares and performed and competed at festivals, were quasi legal because they promoted martial virtue (wude) and actively prepared young men to take the military entrance exam. Boxing groups could be non-religious; However, it is hard to know because they were mainly reported in official documents only when they were part of "meditation" cults. Heterodox religion was more illegal than boxing by itself, even if the sect didn't practice boxing. Still sects were very popular and wide spread.

Most of the time when martial arts are reported in the official histories it is because they were involved in an unorthodox cult. So most of what we know supports the idea that martial arts and religion were intimately connected, we simply don't have much information about non-sectarian martial arts. It is probably true that there were individuals who practiced only forms, applications and sparring like the our modern day stereotypes, but it is very unlikely that "a pure martial arts" lineage or family ever existed. Everybody had a gongfu brother, uncle, or great uncle who crossed over into performance, ritual, religion, banditry or rebellion.

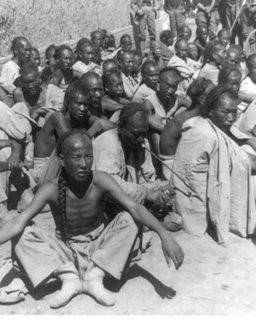

Boxers captured by the Americans

Boxers captured by the AmericansEsherick gives a lot of attention to the overlap between martial conditioning practices like iron t-shirt or golden bell, and invulnerability rituals which incorporate magic, talisman, trance, and possession by local deities and heroic characters from popular opera. There is a continuum from, "Go ahead, hit me, I can take it!" passing through, "Blades always miss me" moving toward, "Due to my amazing qigong, blades can not cut me," and finally ending up with, "Bullets can't harm me, I am a god." Setting aside the question of how well any of these techniques work, it isn't hard to see why 20th Century martial artists, opera performers, religious devotees, and revolutionaries would all want to disassociate themselves from these practices.

In the scramble to invent history, dotted lines have been drawn between "real iron t-shirt" for "real" martial artists, "tricks" used by street performers, "qi illusions" used by magicians and charlatans, and suicidal devotion to a cause--like standing in front of a tank.

It is time to admit that in the 20th Century, embarrassment has been a driving force in the creation and reformulation of martial arts, especial where history is concerned.