Weak Legs

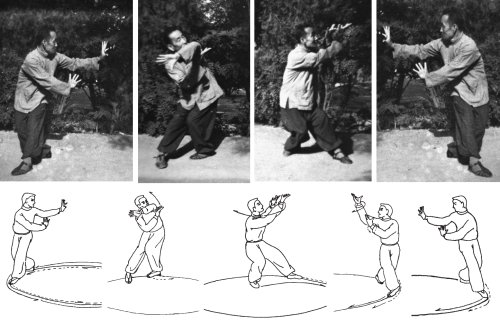

/ A 9 year old student asked me during class the other day if I did any strength training. I did my teacher thing and screwed up one side of my face while bulging out my eye on the other, "No," I replied, "Do you do any strength training?" This kid admitted that he didn't but I could see by the way he looked at the ground that someone had been trying to breed a feeling of deficiency in this kid's head. Now we aren't talking about just any old 9 year old, this kid can walk across the room on his hands and he can do a press handstand from a straddle position on the floor. So I said, "OK, you stand in a low horse stance and I'll put all my weight on your shoulders and you try to lift me up." I leaned down on his shoulders and lifted myself up on to the very tips of my toes so that he had about 150lbs on his shoulders. He then stood up with out even a second thought, lifting me into the air. "That was easy right?" I asked. "You could lift two adults couldn't you?." "Yeah," he said, looking a little brighter. "So you're strong enough already right?" He just looked at me, unsure what to say. "Now you have to figure out how to transfer the force of your legs to your arms. That's what you need to work on." And then we got back to the two-man form we had been working on when he asked the question.

A 9 year old student asked me during class the other day if I did any strength training. I did my teacher thing and screwed up one side of my face while bulging out my eye on the other, "No," I replied, "Do you do any strength training?" This kid admitted that he didn't but I could see by the way he looked at the ground that someone had been trying to breed a feeling of deficiency in this kid's head. Now we aren't talking about just any old 9 year old, this kid can walk across the room on his hands and he can do a press handstand from a straddle position on the floor. So I said, "OK, you stand in a low horse stance and I'll put all my weight on your shoulders and you try to lift me up." I leaned down on his shoulders and lifted myself up on to the very tips of my toes so that he had about 150lbs on his shoulders. He then stood up with out even a second thought, lifting me into the air. "That was easy right?" I asked. "You could lift two adults couldn't you?." "Yeah," he said, looking a little brighter. "So you're strong enough already right?" He just looked at me, unsure what to say. "Now you have to figure out how to transfer the force of your legs to your arms. That's what you need to work on." And then we got back to the two-man form we had been working on when he asked the question.If any of my readers doubt the above anecdote I challenge you to do the experiment yourself. Find a small healthy kid, 5 to 8 years old. Show them how to do a horse stance and then try putting all your weight on their shoulders. As long as the kid's back is straight and her legs are aligned to take weight she should have no trouble lifting you up.

Why is this relevant? Why now?

On my last trip to China I wandered all over Ching Cheng Shan mountain in Sichuan. The "trails" are mostly steep stone stair cases that wind up into the clouds. If you are lazy and have a little cash, you can hire two guys to carry you up three miles of stairs in a litter made with some cloth and two bamboo poles. The guys who do the carrying all day long during the tourist season have pencil thin arms and legs. They are skinny enough to be run-way models at a fashion show. Their leg muscles do not bulge.

Likewise, I studied twice with Ye Shaolong, the second time I trained with him everyday for three months. He is probably the world's greatest master of what George Xu calls "the power-stretch." He uses low, slow expanding movements to develop explosive and suddenly recoiling power. In his 70's, Ye Shaolong is one of the skinniest people I have ever met. He has no muscle.

In my early twenties, with ambitious winds blowing, I took to standing still in a low horse stance with my arms horizontal to the ground out to the sides, for one hour. I did this everyday for a year. (20 years later, I still stand for an hour everyday but not all of it in a horse stance.) For the first few months, my thigh muscles got bigger, but then a funny thing happened. As my alignment and circulation improved, my thigh muscles, my quadriceps, started to shrink. After a year of this kind of practice my thigh muscles were smaller than they had been when I started. And by the way, I wasn't just standing, I was training at least 6 hours a day and I didn't have a driver's license so I was also riding my bicycle up steep San Francisco hills as my sole form of transportation. I'll say it again, my muscles got smaller.

Ouch! That's got to hurt

Ouch! That's got to hurtMost people who practice martial arts actually never learn this because they don't have the discipline to pass through that first gate. At the time, I was just like everyone else, I believed that I needed to improve my strength. I now understand that strength itself is an obstacle to freedom.

The internal arts of Qigong, Daoyin, Taijiquan, Baguazhang, Xingyiquan, and some of the the mixed internal-external arts like Eight Immortals Sword, all have ways of training that do not require building strength. Some Shaolin schools have these methods too. In fact, under the proper guidance of a teacher, with a natural commitment to everyday practice, anyone can use these arts to reveal their true nature. A true nature which, like that of your average 7 year old, is already very, very strong.

On this blog I have explored many justifications for the cultivation of weakness. For instance:

--it makes you more sensitive,

--you need less food (making it possible for more people to eat in times of food scarcity),

--you need less energy to exercise leaving more energy available for other pursuits,

--it's better for circulation in times of less activity (which is what we are doing most of the time anyway),

--your movement is less conditioned to a series of set responses (spontaneously agile),

--and you don't need to wear spandex.

But the number one reason for not developing strength is that healthy human beings are already strong enough. Even 5 year old children are very strong. The problem is that normal human beings have disrupted the integration of natural, untrained strength, into their everyday activities. This happens first of all in the arms, which develop both fine motor coordination and repetitive patterns, both of which leave the arms disconnected from the natural strength of the torso. Also, adult hormones, particularly male hormones, produce muscle really easily if we prime them with lots of food and reckless exercise. By reckless exercise I mean games or athletics that cause injuries. Small injuries to the legs will instantly cause a healthy male to develop big thick quads, it can happen overnight. Once these arm and leg problems are established they become habits. But natural strength doesn't go away, it's waiting for us just under the surface. The real problem, the only real problem, is the fear that we need to be strong to face life's challenges--the notion that we need strength to prevail.

The likelihood of injury from strength training, by the way, is the reason that people who do strength training have to create all sorts of schedules to "cross train" the various muscle groups. These people are now arguing that all training is actually in the recovery! Weird.

And don't get me started on core strength.... OK, it's too late. Core strength is just a marketing scheme, like Green architectural-design-dog-walking-nanny services. It just sounds good or something. It plays on peoples feelings of insecurity and guilt. There is no core that needs strengthening to begin with, but even if such a core existed, the market is saturated. Every type of movement training from Yoga to tiny-tot-tap-dancing now claims to be good for your "core."

And don't get me started on core strength.... OK, it's too late. Core strength is just a marketing scheme, like Green architectural-design-dog-walking-nanny services. It just sounds good or something. It plays on peoples feelings of insecurity and guilt. There is no core that needs strengthening to begin with, but even if such a core existed, the market is saturated. Every type of movement training from Yoga to tiny-tot-tap-dancing now claims to be good for your "core."Here at North Star Martial Arts we specialize in Core Emptying!

That's Right! All negativity is stored in the inner "core"--known traditionally as the mingmen or "gate of fate." Sign up for this once in a lifetime offer of 12 classes for only $99 (that's a $1 discount) and you will get a bonus "card" to keep track of your first one hundred days of Cultivating Weakness! Empty your Core Today! (Say the words "relax your dantian," or Tell them you heard it here at W.W.A.T.)

Like aggressive advertising, strength obscures our true nature.

Martial artists who try to develop strength are preparing themselves for some future attack, the nature of which is yet unknown. I'm not against strength, heaven knows people love it, I'm just against the argument that we need it. Anyone who says Chinese Internal Martial Arts require a person to develop strength is confused about the basic concepts.

note: (If you are a bit of a sadist and want to watch some people squirm, I'm about to post this at the unhinged Internet forum Rum Soaked Fist! check it out.)

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an  Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity).

Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity). Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead.

Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead. The Uncarved Block is one of the primary metaphors for the concept/anti-concept known as wuwei. The Daodejing suggests that we be like an uncarved block of wood. The implication is that once a block of wood is fashioned into something, it loses it’s potential to be something else. Once we make a decision, it cuts off certain options. In other words, it is often good to wait. But the Daodejing isn’t telling us to be indecisive. It doesn’t say, “in difficult situations--waver!” It also doesn’t say be slow, like a tree; or “be inactive,” like a log or a stump. It says be like a partially processed block of wood. Since the Daodejing doesn’t give us any idea how big this block of wood might be, or what it might be for, we can speculate. Our block of wood could be carved into any sort of deity or icon, or perhaps a boat, a cabinet, a ladle, or a coffin. The Daodejing is using this metaphor to point to a process which takes place when we make something. It is not saying, “Don’t make stuff.” Sometimes a decision can position us for more possibilities, sometimes a decision can limit us. Is this better than that? Be comfortable with ambiguity, but have a few uncarved blocks hanging around in case you need them.

The Uncarved Block is one of the primary metaphors for the concept/anti-concept known as wuwei. The Daodejing suggests that we be like an uncarved block of wood. The implication is that once a block of wood is fashioned into something, it loses it’s potential to be something else. Once we make a decision, it cuts off certain options. In other words, it is often good to wait. But the Daodejing isn’t telling us to be indecisive. It doesn’t say, “in difficult situations--waver!” It also doesn’t say be slow, like a tree; or “be inactive,” like a log or a stump. It says be like a partially processed block of wood. Since the Daodejing doesn’t give us any idea how big this block of wood might be, or what it might be for, we can speculate. Our block of wood could be carved into any sort of deity or icon, or perhaps a boat, a cabinet, a ladle, or a coffin. The Daodejing is using this metaphor to point to a process which takes place when we make something. It is not saying, “Don’t make stuff.” Sometimes a decision can position us for more possibilities, sometimes a decision can limit us. Is this better than that? Be comfortable with ambiguity, but have a few uncarved blocks hanging around in case you need them.

The moment I start writing a blog post, or you start reading one, the danger that we will lose sight of wuwei increases. Because reading and writing is a form of carving. The moment we put pen to paper we risk crossing over into the land of methods.

The moment I start writing a blog post, or you start reading one, the danger that we will lose sight of wuwei increases. Because reading and writing is a form of carving. The moment we put pen to paper we risk crossing over into the land of methods. As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background.

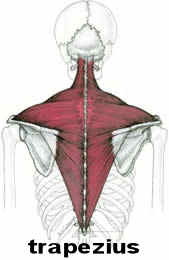

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background. Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.)

Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.) The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.

The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.

I started a new debate thread on

I started a new debate thread on  I may be driving a beat-up 1981 Toyota pickup truck

I may be driving a beat-up 1981 Toyota pickup truck  I'll tell you how. Because I'm doing taijiquan, xingyiquan and Baguazhang. I'm doing internal arts when I do these high kicks. Sure, it looks like Shaolin, but if it wasn't the purest internal practice I can pull off, my muscles would be ripping, my ligament falling off the bone. It's not that it would be impossible to do this kind of practice externally at my age, it's just that the risk of injury is so high, and the healing time for even minor injuries is so long, that I couldn't possibly teach or perform.

I'll tell you how. Because I'm doing taijiquan, xingyiquan and Baguazhang. I'm doing internal arts when I do these high kicks. Sure, it looks like Shaolin, but if it wasn't the purest internal practice I can pull off, my muscles would be ripping, my ligament falling off the bone. It's not that it would be impossible to do this kind of practice externally at my age, it's just that the risk of injury is so high, and the healing time for even minor injuries is so long, that I couldn't possibly teach or perform. presence on the boarder is keeping the peace--yes I can imagine him developing internal arts. He has to practice anyway because he might even see some action if things go badly. But most likely he is going to end up back in his home village, perhaps working on a farm. There is some incentive, but it isn't a very strong one.

presence on the boarder is keeping the peace--yes I can imagine him developing internal arts. He has to practice anyway because he might even see some action if things go badly. But most likely he is going to end up back in his home village, perhaps working on a farm. There is some incentive, but it isn't a very strong one.