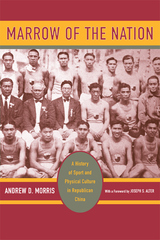

Marrow of the Nation

/ I just finished reading Andrew D. Morris, Marrow of the Nation, A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China, UC Press 2004.

I just finished reading Andrew D. Morris, Marrow of the Nation, A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China, UC Press 2004.Before I tell you about that I just want to say I've got a lot on my plate before I leave for Taiwan and so I apologize if my blogging seems rushed and...

My advanced students from ER Taylor Elementary School are performing again, Saturday May 16th, this time at San Francisco's beautiful new De Young Museum. They'll be on the Outdoor Cafe Stage at 1:45 PM, it's free.

Marrow of the Nation contributes an important piece of history to our understanding of why Chinese Martial Arts History is such a madhouse of unsupportable fiction (and also why, as Chris at Martial Development pointed out, some comic fictional films are closer to the truth than the books historians have written).

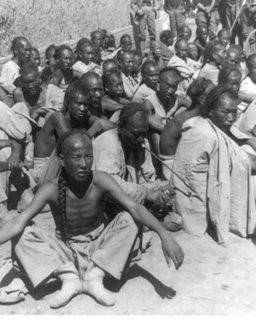

In the early 20th Century Chinese people, particularly urban people, were deeply humiliated. For 300 years they had been under foreign Manchu rulers, forced to wear their hair in a queue as symbolic slaves. The Chinese people saw themselves as collaborators in their own oppression. They were unable to work together to overthrow a weak corrupt government until a group of 9 foreign powers allied to bring China to it's knees. All the foreign powers were Christian, except Japan, and all were promoters of Modernity.

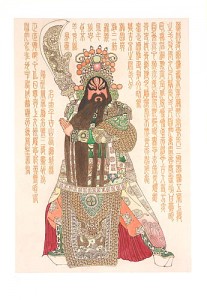

Scientism, Rationalist extremism, absolutist truths, and the relentless quests for purity of form, and transparent clarity--swept the country like wild fire. China turned on itself. Anything old which required oral transmission, anything mysterious, secret, difficult to learn, or regionally particular, was viciously attacked as the cause of China's past failures and humiliations. Thus it was claimed, Martial arts were practiced by dirty herbalists, religious nuts, and desperate performers who gather up ignorant crowds and block traffic.

Martial Arts were to be replaced by tiyu, Physical Culture. By that they meant Western Sports fitness and Olympic style competitions. Physical Education Departments opened up in schools all over the country.

Huges swaths of Martial Arts culture were wiped out, never to be seen again. Imagine having spent your life developing an extraordinary "spirit fist" only to be surrounded by ridicule on a national scale. Most chose to take their secrets with them to their graves, many probably committed suicide.

Those martial artist activists who resisted the onslaught of hysteria did so in the name of Modernity! The first powerful voice for making Kungfu part of Modernity was called The Pure Martial Society (Jingwu Hui). They argued that martial arts could be a sport like any other sport. All the other sports came from the West, having a Sport with Chinese roots would be a great source of pride which would help build the nation. For Kungfu to be a sport it had to be totally open, accessible to women, have a clear standard curriculum, have a health and fitness component free of terms like jing, qi or shen, and be competition oriented. Jingwu swept the country and Chinese communities in South East Asia. As political fortunes changed it was surpassed by the Guoshu (National Art) movement. The Kuomintang Government of Chang Kai-Shek (he was a Methodist Christian) implemented Guoshu schools all over the country, at least where he was in power, and used the competitions along with academic testing to pick officers in his government and armies. But everybody who taught martial arts started calling it Guoshu, meaning that they agreed with the modernizing, scienticization project.

They tended to argue that in the past there was a pure fighting art that had been corrupted and could now be extricated from the mildew of history by being simplified and mixed with fitness training. But there were lots of arguments. Some argued that martial virtues had been lost. This was the period when people started making up lineages and publishing teaching manuals.

The lineages allowed people to pretend they came from a great and pure martial line of masters dedicated to nothing but martial virtue and pure technique. Inventing the lineages allowed people to write religion, rebellion and performance out of history. Some of the lineages may have been real, but they were not pure. By claiming a lineage people were also renouncing the past, both real and imagined, they were saying in effect, 'Now THIS art, which was unfortunately secret for many generations is now totally clear and open! Anyone with four limbs and two ears can learn it!'

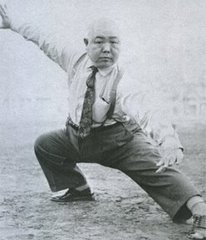

There was a guy named Chu Minyi who served as a minister for the Kuomintang. He invented something called Taijicao (Tai Chi Calisthenics) and in 1933 wrote a book called Tai Chi Calisthenics Instructions and Commands. "Whereas traditional tai chi was simply too difficult for any but the most dedicated martial artist to master, tai chi calisthenics were pleasingly easy to learn and practice." They could be done in a few minutes and they used a counting formula like jumping jacks. He also gets credit in the book for inventing the Tai Chi Ball practices. (Hey, I didn't write the book, but those tai chi ball exercises always looked a little too much like rhythmic gymnastics for my taste.)

Chu's Tai Chi Calisthenics were performed on stage at the 1936 Olympics. Fortunately or unfortunately he was a peace activist and so naturally supported the Japanese when they invaded and was later executed for treason. But not before performing one last taijquan set in front of the firing squad.

Check out the book. All the good stuff is in Chapter 7, "From Martial Arts to National Skills."

This is all great background for understanding Wang Xiangzai's challenge to every martial artist in the country to either fight him or sit down and explain their art in plain language. It explains why he wanted to to throw out forms, shaolin, performance, philosophy, theory, religion, etc... It also helps explain why his students were confused enough to go in three different directions; 1) standing still as a pure health practice, 2) fighting is everything, and 3) knocking people over by blasting them with qi from a distance.

(hat tip to: Daniel)

UPDATE: Here is a video of Chu Minyi! Yeah!