Rather than write a conventional review of the new book

Shaolin Monastery, History, Religion and the Chinese Martial Arts, by Meir Shahar (2008), I've planned a series of connected posts on this and two other books which he relies on heavily. The other titles are:

The Origins of the Boxer Uprising, by Joseph W. Esherick (1987); and

T'ai Chi's Ancestors, the Making of an Internal Martial Art, by Douglas Wile (1999).

Let's start off with Shahar's conclusion:

Why the late Ming? Why was a martial arts synthesis created at that period? The sixteenth century witnessed remarkable economic and cultural creativity, from the growth of domestic and international commerce to the spread of women's education, form the development of the publishing industry to the maturation of new forms of fiction and drama. Hand combat [quan] evolution could be seen as another indication of the vibrancy of late Ming society. More specifically, the integration of Daoist-related gymnastics into bare-handed fighting was related to the age's religious syncretism. A climate of mutual tolerance permitted Shaolin practitioners to explore calisthenic and breathing exercises that had been colored by Daoist hues, at the same time it allowed daoyin aficionados to study martial arts that had evolved within a Buddhist setting. Intellectual trends were joined by political traumas as the Manchu conquest of 1644 convinced the literati of the necessity to explore the folk martial arts. As scholars trained in bare-handed techniques, they rewrote them in a philosophical parlance. The broadening of the martial arts into a self-conscious system of thought was largely due to their practice by members of the elite.

Shahar's expertise is in fiction and literature. Because of that background he makes some really interesting points. But more on that later. I interrupted the quote to point out a few things. First, he uses three different terms for the same group of people: literati, scholars, and elite. Seeing as he draws heavily on Esherick's work, I'm going to presume that he also follows him in defining the said group. Esherick's entire first chapter is dedicated to a statistically based analysis of this very group whom he calls "the gentry." Readers are forgiven for being confused (or bored) by the terms. This literati-scholar-elite-gentry was primarily made up of men who passed the lowest level of imperial exam and yet received no appointment in the government! Such 'men of merit' were often called on by local magistrates to solve local problems, such as gathering information about local cults or organizing a militia to go after bandits. Shahar is really referring to available texts, not to a type of person per se, so literati is a good term and includes celebrated authors, a few of whom were no doubt officials with government appointments. (I hope this clears up some confusion and heat between me and

Dojorat a couple of months back.)

This "self-conscious system" we know to day as martial arts first developed during the Ming Dynasty partly as a result of laws. Chinese notions of law, even today, use the metaphor of a down hill slope. This is distinctly different from Western jurisprudence which uses the metaphor of a line or a wall. The question in the West is, "Did he or didn't he do it?" When we break a law, we step over a line. In China, if you break a law, all of the improper actions leading up to the point when you broke the law are also part of your crime. If you loved putting firecrackers in G.I. Joe dolls as a kid,

you were sliding down the slope, and when if your mother did nothing to stop you, then she is implicated too--when 20 years later you are arrested for blowing up the police station. (Chinese law traditionally required a confession, a tortured one if necessary. And in earlier times it was not unusual to bring a trance-medium into the courtroom to channel murder victims so they could be asked directly who killed them.)

Drawing again on Esherick's work, what Shahar is calling "the age's religious syncretism" was also a set of laws declaring it illegal to make sacrifice to heterodox deities. The positive side of these laws, or the

up hill side in keeping with the metaphor of a slope, was the practice of the three religions (

sanjiao) Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism. The government declared these three different religious traditions were compatible, mutually supporting, and good for the nation. Rolling slowly

down the slope towards heterodoxy, we get the mass of Chinese people participating, as they always have, in a huge diversity of cults to local and national deities. Two factors tended to bring the label of heterodoxy to these cults:

predictions of catastrophe, and

seeking converts (the implications this had for the adoption of Christianity will be covered in a future post). The most common punishment for religious heterodoxy was death for the leaders and dispersion for the followers.

Many cults were divided into two parts, the martial and the civil,

wu and

wen. The

wu, of course, practiced physical stuff like, dance, theater, movement based trance invocation, conduct regulating movement (like qigong), and fighting techniques. The

wen part of the cult practiced, chanting, spells, talisman making, meditation, and other sorts of channeling and trance.

The idea of self-cultivation, or what Shahar here calls "self-conscious systems of thought," emerged because it wasn't considered proselytizing to teach, or encourage people to practice, self-cultivation techniques. Self-cultivation was the government approved way to be religious! But Chinese law being a down hill slope and not a line or a wall, meant that people never knew exactly when they were crossing the line into heterodoxy. (Teaching self-cultivation in which one visualized oneself as the Emperor walking on all fours covered in mud would surely have been punishable by death; but a past Emperor in a nightie, maybe not.)

Anyway, back to Shahar's conclusion. He continues:

The spiritual aspect of martial arts theory was joined by the religious setting of martial arts practice. Temples offered martial artist the public space and the festival occasions that were necessary for the performance of their art. Itinerant martial artists resided in local shrines, where the peasant youths trained in fighting. The temple's role as a location for military practice leads us to a topic we had only briefly touched upon: the integration of the martial arts into the ritual life of the village. Future research, anthropological and historical alike, would doubtless shed much light on peasant associations that combined military, theatrical, and religious functions. Preliminary studies of such local organizations as lion-dance troops and Song Jiang militias (named after Water Margin's bravo) reveal that their performances have been inextricably linked to the village liturgical calendar. The very names of some late imperial martial arts troops betray their self-perception as ritual entities; in the villages of north China, congregations of Plum Flower martial artists are called "Plum Flower Fist Religion" (Meihua quan jiao).

This is not to say that all martial artists were equally keen on spiritual perfection. The traditions of hand combat are extremely versatile, allowing for diverse interpretations and emphases. Whereas some adepts seek religious salvation, others are primarily concerned with combat efficiency; whereas some are attracted to stage performance, others are intent on mental self-cultivation. Various practitioners describe the fruits of their labors in diverse terms.

Of course, Shahar's goal was to answer questions about Shaolin Temple and its connection to martial arts. He does a fair bit of that, which I'll go into later, but as you can see, he places Shaolin Temple in the much larger context of popular theater/religion/culture. Remember, the word

martial in Chinese is

wu, which is also a category of theater, much like

tragedy and

comedy are categories of Western theater traditions.

In a similar vein, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising, makes the following observations. [The "Boxer" Uprising or "Boxers United in Righteousness" (Yi-he-quan, sounds like a martial art doesn't it), was a violent anti-Christian cult in which all members became possessed while fighting. ]:

Anthropologists have often stressed the link between ritual and theatrical performance. In the case of Boxer ritual, the link was particularly direct. Spirit Boxer rituals were always openly performed, and people were attracted to them by the same "hustle and bustle" (re-nao) that drew people to the operas of temple fairs. When they left behind their mundane lives and took on the characteristics of the god that possessed them, the Boxers were doing what any good actor does on stage. It is probably no accident that it was in the spring of 1899, after the usual round of fairs and operas, that the Boxers' anti-Christian activity really began to spread in northwest Shandong; and in 1900 it was again the spring which saw the escalation of Boxer activity in Zhili. On some occasions the Boxers even took over the opera stage, and performed from the same platform that provided their gods.

There is no strict functional division between religion and theatre in Chinese society. (The Chinese would certainly not have understood the opposition between the two that the English and American Puritans saw.) Not only are operas filled with historical figures deified in the popular pantheon, but they provide the primary occasion for collective religious observances. Most Chinese folk religion is an individual or at most a family affair. There is no sabbath and people go individually to temples to pray when they have some particular need. The main collective observance is the temple fair and opera--normally held on the birthday of the temple god. The term for these on the north China plain is "inviting the gods to a performance" (yingshen saihui). The idols are brought out from their temple, usually protected by some sort of tent, and invited to join the community in enjoying the opera. Thus the theatre provides an important ritual of community solidarity--which is of course one reason the Christians' refusal to support these operas was so much resented.

And just to add a little more support from another author talking about an earlier era, Douglas Wile begins the second chapter of his T'ai Chi's Ancestors with this paragraph:

The Mongol dynasty, although short-lived by Chinese standards, nevertheless lasted three generations, long enough for a man to be born and die of old age within its span, Of the three arenas in which martial arts were normally practiced--military, theatrical, and private--the military and private were banned to Han Chinese during this period of foreign rule, and as a result, theatrical martial arts reached unprecedented heights. The civil service examinations being abolished, theatre also became one of the only outlets for literary talent. Literature and martial arts, traditional rivals, now found themselves in the same boat, or should we say, on the same stage. This was also a period of demoralization for the martial spirit in China, as the preeminent empire of the East now found herself not only ruled by Mongol aliens, but the jewel in the crown of their universal empire stretching from Korea to the Danube.

With the restoration of Chines rule during the Ming (1368-1644), the three arenas of martial arts practice once again sprang back to life. Although artillery already played a significant role in military operations, the skill of infantry with swords and spears was still decisive....

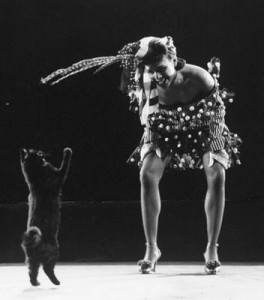

Courtesy of San Francisco Performing Arts Library and Museum

Courtesy of San Francisco Performing Arts Library and Museum