Refuge vs. Treasure

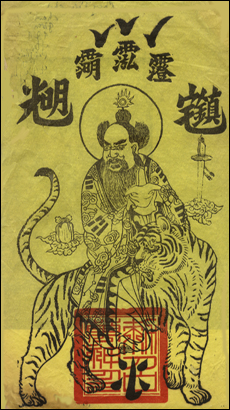

/Religious Daoism makes a distinction between two experiences of practice. These two come into existence because our unconscious or aggressive conduct creates a cleave between the way things actually are and the way we imagine them to be. In the one case, practice is experienced as an absolute treasure because it is a perfect expression of our true nature (de 德) and it permeates everything we do. In the other case, practice is experienced as an incredible nourishing and inspiring refuge from the stress, fear and passions of our daily lives.

In the written literature of Daoism, this distinction has sometimes been couched as the reason Daoism is not for everyone. Religions which encourage practice as a refuge appear to have a big advantage over Daoism. Practice as a refuge may even be addictive or function as a tool for mental clarity or stress reduction. A refuge is easy to sell.

In the written literature of Daoism, this distinction has sometimes been couched as the reason Daoism is not for everyone. Religions which encourage practice as a refuge appear to have a big advantage over Daoism. Practice as a refuge may even be addictive or function as a tool for mental clarity or stress reduction. A refuge is easy to sell.

When we treat practice as a treasure the results are inseparable from all experience. A roller derby helmet becomes part of practice, a loose tooth, the smell of a skill-saw cutting plywood.

We can and do sway back and forth between these two experiences of practice. Some nights before bed, as we are brushing our teeth we think, “I can’t wait to get up in the morning and practice.” That’s what treating practice as a refuge feels like.

Practice as a treasure has no pluses in its camp. Nothing that can be pointed to.

This is the conversation I know about practice; the pull of one, the unbounded unnamable quality of the other.

There really is no conversation I can have of any meaning or significance unless the student already has a practice as solid as stone.

So then I ask the question-- what is the way in? What is the basis for teaching? On what ground does it take root?

In children it is quite obvious that they have potency and access to freedom of movement and openness to learning. Children have a practice, it just has no form because it is still so open to not-knowing, and not-doing. As long as they are not over scheduled they can discover practice.

In adults it is obvious too, in the way people can hold their faces in a mask, or accomplish tasks without thinking, or bring energy, skills and ideas forth to solve a problem. We are capable of these things because of our rituals of “practice,” whatever they may be.

Still, the conversation can not happen until the practice is chosen and one has signed contracts with all their demons to that affect! The ability to make commitments is the single most defining quality that makes us human.

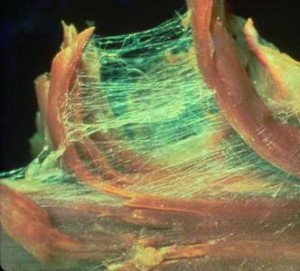

I suppose, I could wander here for a moment into the realm of explanation, though I suspect it will leave me dreaming of my refuge. Practice is another way of saying self-conditioning. It is making deep grooves in our nature and behavior patterns rather than shallow scratches. So Daoist practice is un-self-conditioning. The making of a groove-less groove.

Beautiful music and delicious food, cause the traveler to stop.

Words about the Dao are insipid and bland.

-- Laozi

What are the uses of emptiness?

What are the uses of emptiness?

I love trees. Trees are part of what make us humans human. We have evolved with them. Trees to climb, trees to shelter us, trees to hide us, trees to help us stand up and look around, trees as lookout posts, trees to build with, trees for fire to keep warm and sing and dance and party, trees for sticks to cook, hunt, and fight with, trees to cross rivers, trees to make boats, trees to make tools. And on and on.

I love trees. Trees are part of what make us humans human. We have evolved with them. Trees to climb, trees to shelter us, trees to hide us, trees to help us stand up and look around, trees as lookout posts, trees to build with, trees for fire to keep warm and sing and dance and party, trees for sticks to cook, hunt, and fight with, trees to cross rivers, trees to make boats, trees to make tools. And on and on.

____________

____________