The top Character is Ling

The top Character is LingIt is with trepidation and excitement that I begin this post. The Chinese term

ling is a pivotal taboo concept in North Asian cosmology.

Ling can be translated very roughly as power harnessed from the unseen world. The character is made by writing rain

yu above the character

wu, which has three trance-mediums with their mouths open. Like many taboo subjects it is not the actual word which is taboo, it is the context which matters. For comparison, the word money by itself is not taboo in English, but discussing personal financial data and decisions is. Talking about sex is very taboo, but it’s OK to do it with your therapist and it is expected that you will do it in a socially approved way with your children.

Ling has many common usages and I believe it would be easy for a non-native yet fluent speaker of Chinese to miss their origins--

which are in the fear of unseen forces.

Ling is a common word. In popular usage

ling means agile or dexterous and potent or effective. It can also mean intelligent, clever or tricky. It means spirit, spiritual, mysterious, elf, and it means a coffin with a person in it.

No two languages or societies have exactly the same taboos but there are enough overlaps that English can be helpful here. We have the expressions ‘a smooth talker,’ ‘slippery fingers,’ or ‘nimble fingers,’ all of which describe someone who is good at stealing but can also be used to describe admirable qualities in a person. Someone who makes a ‘killing’ on the stock market can be described as intelligent, agile or ‘sharp as a tack’ because we see him as wielding and manipulating forces other people don’t see or understand. If you get in trouble with the law you may need a lawyer representing you who is both clever and tricky, perhaps one who can call in favors from other attorneys or officials. All of these qualities in Chinese can be described as ling, the ability to harness powers from the unseen world.

My dictionary also has this sweetness which will appeal to horror film fans everywhere, “when a television remote control fails it is do to

ling.” The entry does not state to whom this ling is assigned, but presumably it does not belong to the person who is failing to operate the remote. It is a mysterious unseen force.

Talking about ghosts is taboo in China, rather then say “ghosts” people often refer to them as “our good brothers.” A ghost

(see this article on ghosts) is an intention which is too weak to resolve itself. These unresolved intentions linger about the living looking for enough

qi to complete themselves. When a person dies, most of what she wants, her

will, dies with her. But obviously some of it lingers on. That’s why we write a

last will and testament, we want to avoid having our intentions distorted after we die. After we die our will lingers in things we have said to others, in things we have written and in how our actions are remembered by the living. Without the ‘help’ of the living our intentions would of course disappear. Certain types of intentions can be passed on to others as strange or negative behavior or personality traits. For instance a parent who has a traumatic experience with a dog can easily pass on that fear to a child who has had no such experience. Sometimes quirks are passed on without any obvious content. In the graphic novel

Maus, the son of a Holocaust survivor is obsessive about collecting matches. Even after he learns that his father’s habit of collecting matches developed because matches were a traded commodity in the death camps the son still can’t stop himself. His kitchen drawers are full of match books. This is a ghost, in the form of a behavior. These ghosts are often surrounded by intensely conflicting emotions and strange behavior. Not knowing the reason behind a strange behavior can make it even harder to stop. Lingering conflicting emotions which have no apparent explanation are often passed on to our children. Humans are full of weird quirks we inherit from our families.

If I understand it correctly, Chinese religious custom thinks of negative influences from the dead as ghosts, and positive influences as ancestors. But the principle is the same, and if we could transcend the taboo I suspect it would also be obvious that some positive lingering influence comes from outside the family and some negative influence comes from our direct ancestors.

Most of what I’ve said about ghosts or ancestors up to this point can easily be re-worded into psychological language: Ghosts are unresolved conflicting emotions which linger on after whatever caused them is no longer there.

However, to understand the concept of

ling we must remember that Chinese cosmology does not posit a separation between spirit and substance. There are no outside agents, all things and events are

mutually self-re-creating. Chinese cosmology understands all thought, for instance, as having some substance tied to it. Heaven is tied to earth, the living are tied to the dead. Imagination needs a body to birth it. When you leave your heart with someone, it’s not just a promise without substance, there is a component of it which is biological-- even if we may not be able to see it with a microscope or a blood test yet.

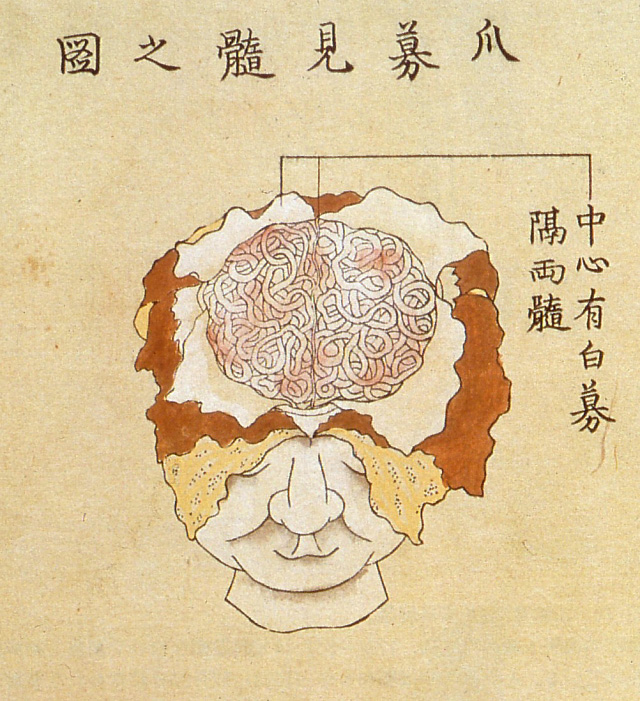

The substance people leave behind when they die is

ling. Intense commitments, pledges, and contracts are often sealed with blood. When I was a kid and we played “Cowboys and Indians” we would sometimes make cuts on our wrists and squeeze the wounds together pledging, “We are now Indian blood brothers forever.” A traditional Chinese contract between sworn brothers requires a smear of deer's blood across the upper lip of each brother. There is a brilliant depiction of this in the movie

“Temptation of a Monk,” about a general who is betrayed during the Tang Dynasty and has to go on the run. The blood in all these cases is

ling.

If you want to make a love potion in Africa, Europe, Asia or America, you need a locket of the persons hair for the spell. The hair is

ling. Voodoo dolls are

ling, so are animal sacrifices and collections of scalps captured in battle.

Every culture has notions of pollution and most cultures have the idea that certain professions are polluting not just to the person doing the job but to his or her decendents as well. In India, Japan, and Korea butchers and people who worked with leather, and people who worked with human waste belonged to hated outsider castes. They were pariahs.

The word pariah is a South Asian word for a drummer. (It’s not clear whether this is because drummers played on goat skin drums or because they were musicians.) In China, leather, human waste, and meat processing were all polluting and the people who worked with these substances were degraded, but they were not pariahs. They were socially above professional musicians and actors who were truly pariah outsiders, literally “mean people.” No one seems to know exactly what was polluting about actors, my best guess after reading

Chinese outcasts: discrimination and emancipation in late imperial China by Anders Hansson, and everything else I could get my hands on, is that it was a combination of two types of pollution. First, actors had a degree of sexual freedom and probably took money for sex some of the time. Second, they were obligated to perform certain expert ritual functions such as exorcisms.

Lingering ghosts are attracted to sexual activity just like they are attracted to fighting. Lingering ghosts need sustenance to keep on lingering and the possibility of spilled blood is a bit like food for ‘hungry’ conflicting emotions. I may be walking out on a dangerous limb here but it seems like the strong moods associated with menstruation are traditionally framed as the spirits of ancestors showing up once a month with a longing to continue their unresolved ambitions through a new birth. “Wasted” semen probably had a similar association. Sex has the potential to produce abortions or illegitimate children. It was of course common for women to die in childbirth and common for children to die before the age of 5. And venereal disease may have contributed something too. All that pleasure we associate with sex mixes in a potent way with all that conflicting emotion and sucks in ghosts like nobodies business.

Musicians and actors, as far as I can tell, were viewed as having a certain amount of sexual freedom, which made them popular and admired, but also contributed to their status as outcasts. It appears that they were often involved in sex for money or sex by obligation as an aspect of entertainment services required of them by regional authorities or powers. Musicians and actors are masters of creating and manipulating mood. In an animist worldview

mood is sometimes viewed as the presence of gods--and the opposite is also true--the presence of the gods is sometimes reified by the acknowledgement of particular moods ("We're all crying, the gods must be here!"). All of this infuses the most potent tools of an actor with

ling, masks come immediately to mind, but I suspect that many implements of the profession had some taint of this

ling.

So ling is the polluted substance itself, the ability to control unseen forces associated with it, and the power which that ability confers. A powerful Daoist priest is said to have

ling. I suspect ritual implements also contain

ling, but can be cleaned. Both purification and emptying practices presumably would remove

ling. Ritual action, be it for exorcism, a funeral or some other purpose, can be understood as the manipulation of

ling. There are at least two ways of looking at.

Ling, as spiritual power, can be accumulated to wield against weaker

ling. Or

apophatically by completely emptying oneself of

ling, the conflicting emotions and deranged powers of ghosts and demons have no place to sink their tentacles and there for they can be controlled. My understanding is that control is not a goal unto itself. The ritual helps ghosts and demonic forces come to completely resolved deaths--or helps them find their way to a realm of safety where they will no longer cause harm to humans.

One of the mechanisms of exorcism is to either destroy

ling, render it neutral or brake its link to the living. It is

ling which is sealed inside pickle jars during exorcisms.

In the realm of martial arts I’ve heard

George Xu talk about the importance of fighting with

ling, which he translates as intelligence. He describes this intelligence as instantaneous, spontaneously expressed knowledge about the best way to fight. It is fighting with the mind but it is not a thought process. It is the ability to wield all available factors like the direction of the sun, variations in the surface of the ground, changing perceptions, leverage, momentum, gravity, sound, emotion, etc... If you saw the recent

Sherlock Holmes movie with Robert Downey Jr. he fights entirely with “intelligence,” 007 does it, and so does the character Michael in the TV series “

Burn Notice.” Of course, on the silver screen we see it in slow motion with narration, in real life it happens faster than the human mind can comprehend. So ling means potency and prowess too.

Gangsters acquire wealth and power by killing, stealing and subordinating people to them. The unseen forces they manipulate are all tainted with ling. Con-men manipulate by tapping into our conflicting emotions and our unfulfilled desires, both of which are traditionally framed as the influence of lingering ghosts. I’ve recently been reading Actors Are Madmen by A.C Scott. Traditionally whoever was in power had a close relationship with the great performers of their region because performers were necessary for ritual and they provided entertainment for all those important banquets which seal agreements between men of prowess and power (

Ling again). S

cott describes Tu Yueh-Sheng a gangster who practically ran Shanghai and controlled all the theaters too. He was a master at manipulating ling. Such people are also often known for being extremely generous protectors of those who subordinate to them. Scott says it was known in Shanghai that if your watch was stolen in the morning you could have it back by evening if you went to the right people, Tu tolerated no competition. But of course getting your watch back would taint you with a little bit of his ling. When a person like this dies, people make shrines to him. At first it is to placate his ghost, but over time people will come to the shrine to ask for favors, a new bicycle, a laptop, a raise. The ling of a gangster takes a particularly long time to resolve because people don’t forget them, we still talk about Al Capone and Jessie James.

Reishi mushrooms

(lingzhi) have

ling in the name because they suck in such complex qi spontaneously form the environment and they are blood red.

Lingshu is the name of the second half of the Han Dynasty classic of medicine, it is usually translated

Spiritual Pivot. Here it refers to the ability to perceive the changing nature of an illness and all of it’s causes-- to find the acupuncture points and the time of day to use them which will reverse the illness with the least harm.

Fengshui is not a tool for redecorating your apartment. The purpose of

fengshui is to limit the influence of the unresolved dead. It is the manipulation of

ling.

One of the great justifications for anthropology is the notion that in our attempt to learn about another culture we mainly end up learning about ourselves. This is particularly true when taking on a subject which is taboo in another culture--both because we end up understanding our own taboos better and because our ‘other culture’ informants are particularly unreliable when it comes to discussing taboos.

Wealth accumulates almost entirely through commerce but kings and bandits accumulate it through violence and taxation. Marx called money “dead labor.” I don’t really care what Marx thought but it does help explain some taboos. Marx was restating a common notion of his time in order to make a distinction between money and capital. Marx’s idea of money was wrong, all money is also capital. All money represents the value of an exchange which is an extremely complex calculation which factors in all previous exchanges of goods and services. Money is a steaming pile of

ling.

Chinese Imperial magistrates enlisted yamen runners and other toughs to serve warrants, bring in criminals, guard jails and torture suspects. Yamen did not get paid by the court, they got all their money from bribes. They were also a degraded caste, not as low as actors but low enough that their children were forbidden to marry a commoner or take a civil or military exam.

Exquisite weapons probably accumulate

ling too. Wars were often commemorated with exorcisms and individual soldiers sometimes sought exorcism to deal with the lingering conflicting emotions of battle. Fighting in wars must have been polluting, but interestingly it was not a polluting profession. A soldier could reach the highest levels of society through marriage, adult adoption and promotion.

One of the things that makes martial arts so fun is the lively mix of danger and power. Of course it is about ling. It is about the manipulation of unseen forces, extreme emotions, extraordinary agility, vigor, sensitivity, and surprise. It is about the possibility of death, guilt, longing, fear, and triumph.

At this point my readers would be forgiven for wondering if there is anything that

doesn’t mean

ling. Terms central to Chinese cosmology like

ling, qi, jing, jin, shen, yi, xin, de, etc...developed by accumulating layers meaning. Most people did not read or write or speak the same dialect as the villages in the next valley, they weren’t making distinctions between “characters” in a dictionary.

This language openness has at times been blamed for the retardation of science in China. Perhaps, but it should also be given credit for preserving a very dynamic world-view which is now giving the rest of the world a much more open idea of what a human body is and what that body is capable of.

Hey, don't look at me. I'm not crazy enough to take on this question. It is the title of a book by Paul Ulrich Unschuld, who is one of the top scholars on the history of Chinese Medicine and Medical Anthropology.

Hey, don't look at me. I'm not crazy enough to take on this question. It is the title of a book by Paul Ulrich Unschuld, who is one of the top scholars on the history of Chinese Medicine and Medical Anthropology.

Saturday morning I crossed the bridge to the bad part of Oakland. The workshop took place in the clubhouse of the notorious

Saturday morning I crossed the bridge to the bad part of Oakland. The workshop took place in the clubhouse of the notorious  Sgt. Rory Miller

Sgt. Rory Miller Back in my twenties I did a lot of two person forearm and shin conditioning. After a while it became really addictive, I just craved that rough contact, it was getting me high. This morning when I went to do my practice I was craving that rough contact again. I never realized this before now, but I think this type of conditioning training is really a way to practice bringing on and dealing with the hormone surge. My morning classes for the last 3 or 4 years have had about 5 minutes of gentle external arm and leg conditioning. But I think my internal practice is giving me another kind of really effective conditioning. My body is primed to instantly pump up when I get the hormone surge. Today I have that Arnold Schwarzenegger feeling in my body. Not stiff--just pumped. I’m sure it will go away in a day or two if I don’t feed it. But it’s an important lesson about how the body works.

Back in my twenties I did a lot of two person forearm and shin conditioning. After a while it became really addictive, I just craved that rough contact, it was getting me high. This morning when I went to do my practice I was craving that rough contact again. I never realized this before now, but I think this type of conditioning training is really a way to practice bringing on and dealing with the hormone surge. My morning classes for the last 3 or 4 years have had about 5 minutes of gentle external arm and leg conditioning. But I think my internal practice is giving me another kind of really effective conditioning. My body is primed to instantly pump up when I get the hormone surge. Today I have that Arnold Schwarzenegger feeling in my body. Not stiff--just pumped. I’m sure it will go away in a day or two if I don’t feed it. But it’s an important lesson about how the body works.

If I understand it correctly, Chinese religious custom thinks of negative influences from the dead as ghosts, and positive influences as ancestors. But the principle is the same, and if we could transcend the taboo I suspect it would also be obvious that some positive lingering influence comes from outside the family and some negative influence comes from our direct ancestors.

If I understand it correctly, Chinese religious custom thinks of negative influences from the dead as ghosts, and positive influences as ancestors. But the principle is the same, and if we could transcend the taboo I suspect it would also be obvious that some positive lingering influence comes from outside the family and some negative influence comes from our direct ancestors.

Beijing Opera (Jingju) has as its most basic physical training something called "da" literally hitting or striking. The warm ups I learned as a kid studying Northern Shaolin are the very same ones used in Beijing Opera. The stage roles are divided into either martial or civil categories (wu and wen). Extensive weapons training is given to everyone because much of the traditional repertoire involves depicting historic conflicts and battles. Probably the best piece of evidence is the most famous Chinese Opera star of the 20th Century, the female impersonating dan

Beijing Opera (Jingju) has as its most basic physical training something called "da" literally hitting or striking. The warm ups I learned as a kid studying Northern Shaolin are the very same ones used in Beijing Opera. The stage roles are divided into either martial or civil categories (wu and wen). Extensive weapons training is given to everyone because much of the traditional repertoire involves depicting historic conflicts and battles. Probably the best piece of evidence is the most famous Chinese Opera star of the 20th Century, the female impersonating dan  "Mean people" were used for everything from entertaining visiting dignitaries, to weddings, to the most sacred rituals of a region. "Opera Families" were profane outsiders who lived in separate districts or separate villages and yet were paid to entertain and purify--to bring order and expel evil.

"Mean people" were used for everything from entertaining visiting dignitaries, to weddings, to the most sacred rituals of a region. "Opera Families" were profane outsiders who lived in separate districts or separate villages and yet were paid to entertain and purify--to bring order and expel evil. Which brings us back to martial arts. Martial arts were used extensively in these rituals. It seems almost too obvious that the basic physical training for popular and rarefied physical theater in China was in fact martial arts training. Each region had it's own style of gongfu (kung fu) and it's own style of theater (ci). But the basic training was the same. It could be refined for either fighting, performing, or both.

Which brings us back to martial arts. Martial arts were used extensively in these rituals. It seems almost too obvious that the basic physical training for popular and rarefied physical theater in China was in fact martial arts training. Each region had it's own style of gongfu (kung fu) and it's own style of theater (ci). But the basic training was the same. It could be refined for either fighting, performing, or both. DATE: Wednesday, January 27, 2010

DATE: Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Elaine Scarry's book

Elaine Scarry's book