Tim Cartmell

/I made my way down to Tim's studio in Huntington Beach around noon. His studio is all mats with big windows and great lighting. It turns out that he currently only teaches the Chinese Internal Arts (Taiji, Xingyi, Bagua) in private lessons and workshops. The classes held in his studio are all Jiujitsu Mixed Martial Arts oriented stuff. There were a few guys in their twenties hanging around and a few showed up around the time I did. Tim told them they could practice their grappling over on the side while we used the center of the space for my lesson.

My sense is that Tim has created a sold institution. His studio is a place where mostly guys in their twenties can come and let loose. A place where it is safe to learn ethics and explore natural aggression. This kind of milieu is an enormous gift to any community and I was both impressed and inspired by it. If students are interested, the internal arts are their for them too, but they are not the main product he is selling. I like that, it takes the economic pressure off of a tradition which really requires adoption levels of intimacy to learn.

Personally Tim was warm and welcoming. His teaching was very clear and it matched his theory. He showed me the first two palm changes of the Sun style of Baguazhang and tested my structure through out the movements. He showed a couple of applications which involved close contact throws. Over the years I've learned many versions of the single and double palm change but each time I learn a new one it is like opening a different window into the original physicality of this arts distant past.

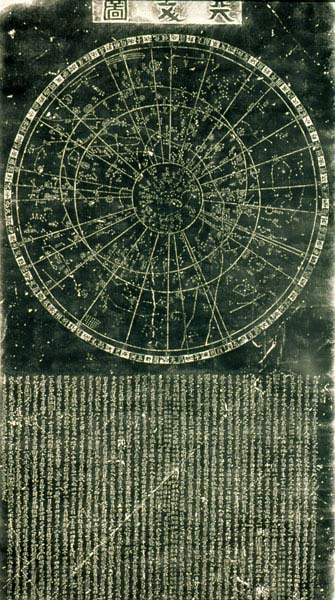

At one point in the second palm change there is a heel spin with both feet turned out. A bit like Indian Classical Dance but since we were working on a mat I was having trouble with the spin. So Tim showed me a straight line practice in which turning in (kou) and turning out (bai) alternate with a spin. I immediately recognized the stepping pattern from a diagram for walking an Yijing (I-Ching) hexagram found in Jo Riley's book Chinese Theatre and the Actor in Performance. We had a short discussion about it and he seemed genuinely interested but obviously it was a much longer conversation for another time. (I don't have Riley's book handy but if anyone does and wants to scan that page for me I'll post it in an update.)

I only had one lesson with Tim so it is quite likely that I misunderstood something or only saw a small part of what he does. But this is what I got. Tim's idea is to use a very soft-light touch with precise footwork to attain a strategically superior position. From there he uses superior structure to close in, at which point an effortless throw happens. During the throw I noticed him melting his structure some what, becoming heavier like water. So he appears to have three modes: soft-light touch, structure, and water.

I think this is an excellent method and I highly recommend Tim as a teacher for anyone living near Huntington Beach. The method is very close to the one I practiced for may years but I've since changed my theory. However, I still believe that what Tim is teaching is necessary to learn, it is probably more exact to say that that I think of it as a developmental stage in a larger theory.

I've explained my theory countless times but it comes out a little different each time, so once more with gusto.

Structure training is necessary because everyone is already using structure even without any training. Structure training teaches you exactly what the best possible structure is so that 1) you can break someone else's structure when you encounter it and 2) so that you are familiar enough with the feeling of structure in your own body that at a more advance level you can totally discard it as a strategy for yourself.

Water training is a necessary stage leading to total emptiness. Water is not very effective for fighting on its own, but it is a superb aid to fighting in close contact --throw or be thrown-- situations because it allows you to add weight anywhere at will. Water is also useful for avoiding strikes and for rolling on the ground.

The importance of learning to achieve a spatially and structurally advantageous position should not be underestimated. The best way to learn this is to practice with a very light sensitive touch, weakened, so as not to rely on strength. In this weakened state you will lose unless you truly have the best position, the position of dominance. With practice you will slowly get better at finding that position. Once you are good at this, you will always know if you have a great position or a terrible one. The next step is to always practice from a terrible position, that way no matter what position you get into you can still fight.

In order to fight well from a terrible position you need to transform from water to steam and from steam to emptiness. Steam will give you the superior power but it is slow. Emptiness will make you fast again and make it impossible for your opponents to feel your intent until it is too late.

Most of my current theory developed from recent encounters with George Xu, and since he is constantly changing his theories I suspect my theories will keep changing too.

Tim has tons of videos and discussions available on the web...Check it out. Tim was very cool about setting up lessons, so if you are near Los Angles drop him a line.

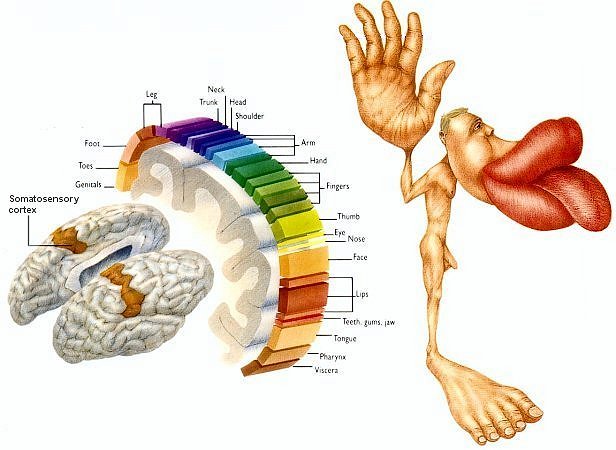

They say we use only a small portion of our brain, and that of the small part we do use, about

They say we use only a small portion of our brain, and that of the small part we do use, about

Michael Saso has his own

Michael Saso has his own

What is going on here? Could this unity harmony thingy explain why Google was able to find the compromise of moving it's operations to Hong Kong?

What is going on here? Could this unity harmony thingy explain why Google was able to find the compromise of moving it's operations to Hong Kong? And of course the Taiji symbol itself is the most ubiquitous image of harmony. It graphically dipicts simultaneous individuation--two distinct things working together inside of each other. But that just starts to sound weird, so lets have an example.

And of course the Taiji symbol itself is the most ubiquitous image of harmony. It graphically dipicts simultaneous individuation--two distinct things working together inside of each other. But that just starts to sound weird, so lets have an example. The shell of the egg is the boundary of our perception. When we practice internal gongfu the shell is the sky and the horizon--as we see, feel, hear, smell and imagine it. We call this shen (spirit) in martial arts. It contains the yolk and the egg white. In basic training we develop the yolk (the body) so that it is smooth, round, and able to shift and change like a thick liquid which can expand and condense in all directions. Then the yolk itself becomes so quiet that we forget it! We forget it like we would forget our own body in the presence of a beauty beyond words. We move only the egg white, shifting and swirling within an enormous shell, and the body follows without effort or inhibition. That's harmony.

The shell of the egg is the boundary of our perception. When we practice internal gongfu the shell is the sky and the horizon--as we see, feel, hear, smell and imagine it. We call this shen (spirit) in martial arts. It contains the yolk and the egg white. In basic training we develop the yolk (the body) so that it is smooth, round, and able to shift and change like a thick liquid which can expand and condense in all directions. Then the yolk itself becomes so quiet that we forget it! We forget it like we would forget our own body in the presence of a beauty beyond words. We move only the egg white, shifting and swirling within an enormous shell, and the body follows without effort or inhibition. That's harmony. Beijing Opera (Jingju) has as its most basic physical training something called "da" literally hitting or striking. The warm ups I learned as a kid studying Northern Shaolin are the very same ones used in Beijing Opera. The stage roles are divided into either martial or civil categories (wu and wen). Extensive weapons training is given to everyone because much of the traditional repertoire involves depicting historic conflicts and battles. Probably the best piece of evidence is the most famous Chinese Opera star of the 20th Century, the female impersonating dan

Beijing Opera (Jingju) has as its most basic physical training something called "da" literally hitting or striking. The warm ups I learned as a kid studying Northern Shaolin are the very same ones used in Beijing Opera. The stage roles are divided into either martial or civil categories (wu and wen). Extensive weapons training is given to everyone because much of the traditional repertoire involves depicting historic conflicts and battles. Probably the best piece of evidence is the most famous Chinese Opera star of the 20th Century, the female impersonating dan  "Mean people" were used for everything from entertaining visiting dignitaries, to weddings, to the most sacred rituals of a region. "Opera Families" were profane outsiders who lived in separate districts or separate villages and yet were paid to entertain and purify--to bring order and expel evil.

"Mean people" were used for everything from entertaining visiting dignitaries, to weddings, to the most sacred rituals of a region. "Opera Families" were profane outsiders who lived in separate districts or separate villages and yet were paid to entertain and purify--to bring order and expel evil. Which brings us back to martial arts. Martial arts were used extensively in these rituals. It seems almost too obvious that the basic physical training for popular and rarefied physical theater in China was in fact martial arts training. Each region had it's own style of gongfu (kung fu) and it's own style of theater (ci). But the basic training was the same. It could be refined for either fighting, performing, or both.

Which brings us back to martial arts. Martial arts were used extensively in these rituals. It seems almost too obvious that the basic physical training for popular and rarefied physical theater in China was in fact martial arts training. Each region had it's own style of gongfu (kung fu) and it's own style of theater (ci). But the basic training was the same. It could be refined for either fighting, performing, or both.