Qigong Fever

/ If this book I'm holding here had been published in 1997 instead of 2007, I probably wouldn't have set out to write my own book on the history and cultural origins of qigong. I also probably wouldn't have failed in that endeavor and ended up putting my collection of writings up on the Internet in the form of a blog called "Weakness with a Twist”and you wouldn't be reading it!

If this book I'm holding here had been published in 1997 instead of 2007, I probably wouldn't have set out to write my own book on the history and cultural origins of qigong. I also probably wouldn't have failed in that endeavor and ended up putting my collection of writings up on the Internet in the form of a blog called "Weakness with a Twist”and you wouldn't be reading it!

Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China, by David A. Palmer. Published by Columbia University Press, 356 pages.

The book is a history of Qigong, which appropriately frames the subject as a political movement built around a body technology with religious characteristics, and scientific pretensions. It is a book which resists symmetrization. Never the less I'm going down that road.

Qigong Fever tells a really shocking story of mass hysterical enthusiasm. The kind of popular insanity that can only happen in a world where 2+2=5 if the Party says it does! The state in essence banned religious devotion, magic tricks, spontaneous expression, deep emotion, and even self-respect. The Party claimed to be in favor of using science to save the world, but obviously science cannot be practiced in an environment where 2+2 might equal 5. It was from this skewed environment that qigong came to be capable of healing anything and everything. All over China otherwise ordinary people could see with their ears, control guided missiles with their minds, tell the future while balancing on eggs—qigong became the source for the development of everything weird, magical, new age, charismatic, and psychic. That all this could happen in the name of science would already be beyond normal comprehension, but the Communist Party brought what would otherwise have been just weird and wacky to a fever pitch by issuing an order essentially forbidding skepticism.

The title Qigong Fever refers to the explosion of interest and participation in qigong methods, research, charismatic religion, and a whole lot more that reached a peak in the decade from 1985 to 1996, after which the government cracked down on qigong people in general and particularly on the followers of the dangerously unbalanced Li Hongzhi, known collectively as Falungong.

Palmer tasks himself with creating a historic record for a subject that is made up of seemingly limitless false claims and (even more challenging for the historian) partially false claims about its origins and functions. In addition he tackles problems as an anthropologist carefully milking the overlapping realms of scientism, charisma, national consciousness, repression, religious impulse, and shifting political networks into a frothy qi infused tonic.

The political alliance that made the qigong movement possible eventually fell apart creating outlaws and refugees. The last chapter of the book deals specifically with the Falungong and its transformation from a qigong cult into an outlaw and exiled revolutionary utopian movement.

The book has a lot of footnotes. Palmer draws on a wide array of original Chinese sources for historical material and makes good use of the history of ideas. His writing moves easily between telling the story, putting it in context, and bringing in other peoples ideas and research to convey the depth of his analysis.

If you like this blog you'll like this book.

In the Early 90's when

In the Early 90's when  A more common use of the word Yi, one that nearly all Chinese martial arts teachers use, means to have an awareness of technique. A student has yi in his form when a knowledgeable observer can see the fighting idea in the students movement. Numerous throws, joint breaks, and striking combination possibilities should be apparent.

A more common use of the word Yi, one that nearly all Chinese martial arts teachers use, means to have an awareness of technique. A student has yi in his form when a knowledgeable observer can see the fighting idea in the students movement. Numerous throws, joint breaks, and striking combination possibilities should be apparent. Practicing at this yi level also feels like clouds, or sometimes like water, fire or mist. Once a practitioner reaches this level, she stops thinking in terms of techniques.

Practicing at this yi level also feels like clouds, or sometimes like water, fire or mist. Once a practitioner reaches this level, she stops thinking in terms of techniques. Dave Randolph

Dave Randolph not necessarily strong and that will creates circulation issues. But proper strength training, and I’m speaking of barbells & dumbbells, but things like kettlebells, clubbells, sandbags etc, that teach full body integration and coordination, causes so many positive responses the body in terms or weight control, mobility, flexibility, coordination not to mention the positive effects on hormonal balances, sleep, digestion, among other things

not necessarily strong and that will creates circulation issues. But proper strength training, and I’m speaking of barbells & dumbbells, but things like kettlebells, clubbells, sandbags etc, that teach full body integration and coordination, causes so many positive responses the body in terms or weight control, mobility, flexibility, coordination not to mention the positive effects on hormonal balances, sleep, digestion, among other things restrict qi circulation, and they compress qi as well.

restrict qi circulation, and they compress qi as well. Monks in Asia carry water on their shoulders, people in Africa and South America carry it on their heads. The skill of carrying water is to continuously transfer all of the weight to the ground and not take any of it in your muscles. Since water tends to slosh around, this requires constant movement and is perhaps one of the reasons we see such great hip articulation in dances like the Samba and the Rumba.

Monks in Asia carry water on their shoulders, people in Africa and South America carry it on their heads. The skill of carrying water is to continuously transfer all of the weight to the ground and not take any of it in your muscles. Since water tends to slosh around, this requires constant movement and is perhaps one of the reasons we see such great hip articulation in dances like the Samba and the Rumba. I think the

I think the  trong fingers, and I'm undefeated in thumb wrestling. Also, I'm not saying only use two fingers, I'm saying test whatever you are about to lift with two fingers. After the test feel free to add the other fingers, a hip, a chin, or even a whole arm. (And we've all heard the story about the lady who flipped over a car because her baby was underneath it. If you're healthy and you really need the strength, it'll be there.)

trong fingers, and I'm undefeated in thumb wrestling. Also, I'm not saying only use two fingers, I'm saying test whatever you are about to lift with two fingers. After the test feel free to add the other fingers, a hip, a chin, or even a whole arm. (And we've all heard the story about the lady who flipped over a car because her baby was underneath it. If you're healthy and you really need the strength, it'll be there.) re in the business of rescuing people and their kids. This is great stuff. I admire the business model. But it does raise the question, do firefighters really need extra strength?

re in the business of rescuing people and their kids. This is great stuff. I admire the business model. But it does raise the question, do firefighters really need extra strength? ever a city official with balls comes along, the Unions go to the sentimental-fireman-gushing-voters and have that official castrated.

ever a city official with balls comes along, the Unions go to the sentimental-fireman-gushing-voters and have that official castrated. When I was studying Chen Style Taijiquan with Zhang Xuexin we practiced outdoors in San Francisco which can be quite foggy even in the Summer. One day he showed us how many layers of long underwear he had on: Five, plus a pair of polyester slacks. Keeping my legs warm has been a part of my practice ever since, but I've never gotten past two pairs of long underwear, and that on a very cold day.

When I was studying Chen Style Taijiquan with Zhang Xuexin we practiced outdoors in San Francisco which can be quite foggy even in the Summer. One day he showed us how many layers of long underwear he had on: Five, plus a pair of polyester slacks. Keeping my legs warm has been a part of my practice ever since, but I've never gotten past two pairs of long underwear, and that on a very cold day. that is that most underwear has tight elastic which can really cut off circulation. Elastic tends to shrink, so even a comfortable pair of underwear can become uncomfortable over time. I don't know about you guys (ladies?) but I need to have my kua open when I practice. I need to feel the "gate" between my torso and my legs surging with qi, or blood/lymph, or breath, or whatever you want to call it. Inhibition sucks.

that is that most underwear has tight elastic which can really cut off circulation. Elastic tends to shrink, so even a comfortable pair of underwear can become uncomfortable over time. I don't know about you guys (ladies?) but I need to have my kua open when I practice. I need to feel the "gate" between my torso and my legs surging with qi, or blood/lymph, or breath, or whatever you want to call it. Inhibition sucks.

When I first met my current partner I was so frustrated I had taken to snipping the elastic with a pair of scissors, which looked mangy and which she was kind enough to remind me of at a party last night.

When I first met my current partner I was so frustrated I had taken to snipping the elastic with a pair of scissors, which looked mangy and which she was kind enough to remind me of at a party last night. On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on

On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on  it seems like a good time to link to my own "

it seems like a good time to link to my own "

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism.

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism.

their students or clients that I don't get. If you tap into a client's insecurities, or their desire for power, by convincing them that they will be freer, or happier, or stronger, or more preceptive, or even more intuitive, if only they quit eating fried chicken and do some groovy breathing exercise--who am I to get in the way? Those commitments are legitimately good for one's health. Other people are free to subordinate themselves to people and ideas.

their students or clients that I don't get. If you tap into a client's insecurities, or their desire for power, by convincing them that they will be freer, or happier, or stronger, or more preceptive, or even more intuitive, if only they quit eating fried chicken and do some groovy breathing exercise--who am I to get in the way? Those commitments are legitimately good for one's health. Other people are free to subordinate themselves to people and ideas. As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism.

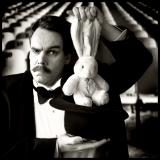

As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism. If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow.

If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow. Chinese popular religion is pretty dynamic. This

Chinese popular religion is pretty dynamic. This  Daoist priests are also called Tianshi (Celestial Masters) because they are responsible for determining, managing and updating the hierarchy of gods. The Rabbit god falls under the control of the City God. The shrine to the City God was likely the focal point of martial arts training during the Song Dynasty, and is the context from which the word gongfu (Kungfu) got its meaning. Gongfu means "meritorious action," people training martial arts on behalf of the community did so as part of their participation in the cult of the City God.

Daoist priests are also called Tianshi (Celestial Masters) because they are responsible for determining, managing and updating the hierarchy of gods. The Rabbit god falls under the control of the City God. The shrine to the City God was likely the focal point of martial arts training during the Song Dynasty, and is the context from which the word gongfu (Kungfu) got its meaning. Gongfu means "meritorious action," people training martial arts on behalf of the community did so as part of their participation in the cult of the City God.