Bowing

/ There is a Daoist precept against subordination. In fact there is a precept (one of the 180 of Lord Lao) that says, "Do not serve in the military. If you must serve in the military do not serve in a subordinate position." I take this to mean join as an officer and be in a position to make decisions about life and death.

There is a Daoist precept against subordination. In fact there is a precept (one of the 180 of Lord Lao) that says, "Do not serve in the military. If you must serve in the military do not serve in a subordinate position." I take this to mean join as an officer and be in a position to make decisions about life and death.I think people living as we do in a commercial society find the idea of not being subordinate both appealing and at times unworkable.

(Currently I feel subordinate to my web hosting service and my ISP which are never able to solve all the weird intermittent and indeterminate problems I have in my daily struggle/walk-in-the-sun to publish my blog. 2 hours on the phone, zero results. If you occasionally get a “Yahoo 404 Error� or a "500 error" when you try to read my blog, I’d love to hear from you.)

What is the purpose of bowing? A traditional class has at least three bows. The first bow is done upon entering the space. Why bow to the space? This tradition comes out of the shamanic practice of subordinating oneself to allies (gods, spirits, ancestors) in exchange for power. The power one gets through subordination is then used to exorcise, scare away, or subordinate all other beings in a given space. It is often called "purification." (Today at the farmer’s market I watched a large man attempt a rather weak version of purification while swinging a bible and shouting in a horse voice about revelation.)

The Japanese term Dojo means Hall of the Dao. It most likely comes from Sung Dynasty (900-1200 CE) Daoism. Clan halls, trade halls, and halls associated with the mega-deity-category "Earth," were used as community centers, places for everything (Dao). When you entered one of these halls to practice gongfu (meritorious martial training) it was important to clear the space of spirits that might try to possess you--dangerous spirits are particularly attracted to weapons and those who wield them.

When a shaman purifies a space, she uses her acquired strength to forcibly evict all the ghosts and spirits that have taken up residence there. Since Daoists did not practice subordination to other entities and they were weak by precept and commitment, they didn’t actually purify the space immediately. Instead they bowed. The act of bowing is a declaration that human beings are going to temporarily use the space for meritorious actions. Bowing doesn’t scare away ghosts, or banish them. Bowing is a way of asking spirits to temporarily clear out. It is a declaration that the practice about to be performed will not be of any interest to ghosts. A ghost is an entity defined by weak, deficient, or lingering commitments.

When a shaman purifies a space, she uses her acquired strength to forcibly evict all the ghosts and spirits that have taken up residence there. Since Daoists did not practice subordination to other entities and they were weak by precept and commitment, they didn’t actually purify the space immediately. Instead they bowed. The act of bowing is a declaration that human beings are going to temporarily use the space for meritorious actions. Bowing doesn’t scare away ghosts, or banish them. Bowing is a way of asking spirits to temporarily clear out. It is a declaration that the practice about to be performed will not be of any interest to ghosts. A ghost is an entity defined by weak, deficient, or lingering commitments.The second bow is usually to the teacher. The teacher joins this bow because the bow is not to the person but to the teaching itself. It is as if all the teacher’s teachers are standing behind him and he ducks so that the bow of the students will fly over his head to be received by all of the ancestors of the teaching itself.

(In many schools, before and after working with a partner people will bow to each other as equals. This bow again represents a declaration to practice only acts of merit.)

The third bow is to give up the space to who ever or what ever is going to use it next. It cautiously invites the spirits back. After doing this ritual in a space for several years the spirits attracted to dangerous behavior or people with weak commitments will have had time to find another place and will have moved on. Through this continual demonstration of acts of merit (gongfu) some spirits will have found the strength to complete themselves and become one with Dao. Thus we call this place a Dojo, a hall of the Dao.

On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on

On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on  it seems like a good time to link to my own "

it seems like a good time to link to my own " I want to announce that we have officially entered the Era of Conditioning.

I want to announce that we have officially entered the Era of Conditioning. I'm anti-conditioning. I believe in doing things form the inside out. If I said, "I believe in beginning from the heart," you could accuse me of being a silly romantic. But it's not because I want to bring out genius, or preserve mystery, I just prefer spontaneous unconditioned responses.

I'm anti-conditioning. I believe in doing things form the inside out. If I said, "I believe in beginning from the heart," you could accuse me of being a silly romantic. But it's not because I want to bring out genius, or preserve mystery, I just prefer spontaneous unconditioned responses.

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism.

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism. As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism.

As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism. If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow.

If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow. In an earlier post I talked about the invocation of

In an earlier post I talked about the invocation of  teaching, except to say, "sit still."

teaching, except to say, "sit still."

The last chapter of

The last chapter of

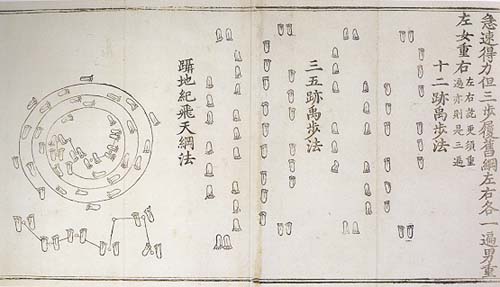

something different. Here is a fun one (#33). The Chinese title is "not-two-natural-principle" The authors' translated it "Accuracy Method.":

something different. Here is a fun one (#33). The Chinese title is "not-two-natural-principle" The authors' translated it "Accuracy Method.":