Zhang Daoling

/Who Was Zhang Daoling?

Zhang Daoling is the founder of Religious Daoism (Daojiao), the Celestial Masters (Tianshidao) and Orthrodox Daoism (Zhengyidao). All Daoist lineages trace their inspiration back to him. He was born in Eastern China and as a child studied with five fangshi, which was a general term used for shaman-doctors. These fangshi were probably experts in ritual, healing, and trance. Still in his youth, Zhang traveled to Western China, to the area we know as Sichuan. There he went into solo retreat in a cave on Heron Call Mountain (Hemingshan).

The revelations of Lao Jun

When Zhang Daoling came out of retreat in 142 CE he began teaching publicly and healing the sick. He said that he had met Lao Jun (Lord Lao), the source and the original inspiration for the Daodejing

True for all time and in all eras

Zhang taught that Lao Jun’s revelations had appeared to humans many times throughout history, transmitted through ‘seed people,’ such as himself and Laozi the original author/compiler of the Daodejing

Healing by Commitment

Healing by CommitmentZhang performed healing ceremonies in which part of the healing process was a commitment on the part of the person being healed to change their behavior. He began the method of making written talismanic contracts called fu, which were burned, put in water, or buried in the earth as a way to reify peoples new commitments. This brought about healing among his followers. Some of the talismanic style of writing he produced is still copied and used today.

A Daoist Country

Zhang Daoling’s following grew steadily and his teachings were carried on by his descendants. By the time of his grandson Zhang Lu, the Celestial Masters had founded a small country. Each family contributed five pecks (a bushel) of rice, and thus for a time early Daoism was called the Five Pecks of Rice school. Zhang Daoling is still represented in ritual as a bowl of rice with the tip of a sword stuck straight down into it.

The country they founded was approximately 40 miles across, was multi-ethnic, and from what we know it was administered very successfully from 190 until 215 CE. When the general Cao Cao swept across China with a huge army, Zhang Lu personally rode out to meet him and the two forged an agreement. The Wei Dynasty which Cao Cao founded was short lived (215-266) but his agreement with Zhang Lu allowed Daoist priests to be spread throughout every part China.

Sacred Texts

Zhang Daoling and Zhang Lu both wrote commentaries on the Daodejing which are still read today (though parts of each have been lost). Zhang Lu is the author of several of Daoism’s founding texts, including the Xiang’er Precepts and The Commandments and Admonitions for the Families of the Great Dao.

Zhang Daoling, his sons, his grandsons and all of their wives reach the highest level of xian known as "rising up in broad daylight with one’s dogs and chickens!" (Xian is usually translated ‘immortality’ or ‘transcendence’.)

On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on

On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on  it seems like a good time to link to my own "

it seems like a good time to link to my own "

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism.

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism. As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism.

As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism. If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow.

If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow. Chinese popular religion is pretty dynamic. This

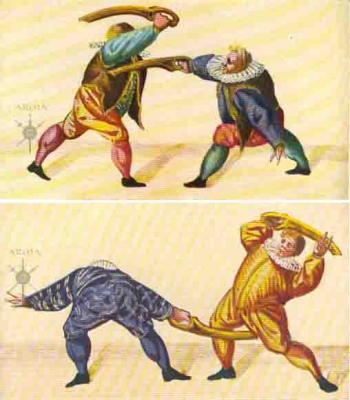

Chinese popular religion is pretty dynamic. This  Daoist priests are also called Tianshi (Celestial Masters) because they are responsible for determining, managing and updating the hierarchy of gods. The Rabbit god falls under the control of the City God. The shrine to the City God was likely the focal point of martial arts training during the Song Dynasty, and is the context from which the word gongfu (Kungfu) got its meaning. Gongfu means "meritorious action," people training martial arts on behalf of the community did so as part of their participation in the cult of the City God.

Daoist priests are also called Tianshi (Celestial Masters) because they are responsible for determining, managing and updating the hierarchy of gods. The Rabbit god falls under the control of the City God. The shrine to the City God was likely the focal point of martial arts training during the Song Dynasty, and is the context from which the word gongfu (Kungfu) got its meaning. Gongfu means "meritorious action," people training martial arts on behalf of the community did so as part of their participation in the cult of the City God. If it is true that, at the time the various taijiquan postures got their names the main people practicing taijiquan were

If it is true that, at the time the various taijiquan postures got their names the main people practicing taijiquan were  Here I continue my commentary on The

Here I continue my commentary on The  If you haven't read Yang-Chu, I recommend it. Yang-Chu is considered one of the early voices of Daoism (300 BCE), a voice for wuwei.

If you haven't read Yang-Chu, I recommend it. Yang-Chu is considered one of the early voices of Daoism (300 BCE), a voice for wuwei. first heard this I was in shock for a few days. Why was I bothering with all the little details, like doing the dishes and "communicating" if almost all the significant data was in a 15 minute video interview? Is it possible that we really don't have free will?

first heard this I was in shock for a few days. Why was I bothering with all the little details, like doing the dishes and "communicating" if almost all the significant data was in a 15 minute video interview? Is it possible that we really don't have free will? The ninth precept, yielding to others, is wuwei. The first precept probably works better in English as "Be Honest." The second precept is often the tough one for people. The flexibility part sounds cool, but the weakness part is confusing. Here is what

The ninth precept, yielding to others, is wuwei. The first precept probably works better in English as "Be Honest." The second precept is often the tough one for people. The flexibility part sounds cool, but the weakness part is confusing. Here is what  It's been a busy weekend but I've been reading this

It's been a busy weekend but I've been reading this