The Banquet

/ Sometime last year I was talking with George Xu and a few other people out in the park. We were talking about making mistakes, ways of training, and the unique skills of various martial arts masters. George filled his torso with qi and turned it to the side in the opposite direction of his chin, then he put one hand behind his back and with the other he made the "lan" movement, a horizontal clearing action like opening a sliding door. All this was a simultaneous gesture to accompany the statement, "If anyone can show me a mistake I am making in my gongfu, any mistake at all, I will right away throw a banquet for that person!"

Sometime last year I was talking with George Xu and a few other people out in the park. We were talking about making mistakes, ways of training, and the unique skills of various martial arts masters. George filled his torso with qi and turned it to the side in the opposite direction of his chin, then he put one hand behind his back and with the other he made the "lan" movement, a horizontal clearing action like opening a sliding door. All this was a simultaneous gesture to accompany the statement, "If anyone can show me a mistake I am making in my gongfu, any mistake at all, I will right away throw a banquet for that person!"Now, being the person I am, with the agenda I have, I must point out to my readers the obvious theatricality of his gesture. Despite the fact that he has generally focused only on the fighting aspects of martial arts, he has obviously acquired some theatrical skill. But why a banquet?

The answer has to do with the importance banquets have in Chinese culture in creating, establishing, transforming, and re-making, patronage networks and alliances.

Many years ago, I showed up a little late to a modest banquet George Xu was putting on for a visiting martial arts master at a local restaurant. The visiting master, about 10 of George's students, a translator and an official from the Chinese consulate, were all already seated when I arrived. As I walked up to the table I made some unconscious sound, I don't know what it was. But suddenly people at the table in front of me split apart and someone gave up a seat for me. The seat they gave me was right next to the translator who was a woman probably in her 40's. As I sat down, introductions were made, everyone took a second to acknowledge me and then the woman translator leaned over and whispered something in Shanghai dialect in my ear. I whispered back an apology in English saying that I really didn't understand any Chinese. The conversation at the table was mostly focused on asking the visiting Master questions. We were taking turns posing questions to be translated. When it was my turn, I asked about the master's early training, how old he was when he started training and what style he studied first. Before the question was translated George looked at me and said, "That is a stupid question, who cares? you waste time." As we ran out of good questions to ask, conversations broke out around the table. The translator and I started talking about this and that, and then she said, "You have a really good Chinese accent. Excellent." Again I told her that my Chinese was quite limited. She ignored this and complemented me again. It was so weird. I asked her, and other Chinese speakers at the table what was going on. Why didn't she believe me? It turned out that whatever that sound was that I made as I walked up to the table was heard as some kind of entirely appropriate status commanding greeting. No one seemed willing to believe that I could make such a sound by accident.

Here is a description of the basic ranking at a banquet.

George Xu told me recently that in China when people throw banquets for him, since he doesn't smoke, no one at the table smokes. This is often appreciated by the guests because it means they get to save money on cigarettes. Normally, if there is a higher status master at the banquet, George will sit next to the right of the other master and be forced to inhale all the second hand smoke. The way it works is that there is a pecking order in which people are allowed to offer the master cigarettes. As soon as he finishes one, the next person in the chain will offer, and so on. I imagine that it would be a big deal, though invisible to an outsider, if the master accepted a cigarette out of order.

George Xu told me recently that in China when people throw banquets for him, since he doesn't smoke, no one at the table smokes. This is often appreciated by the guests because it means they get to save money on cigarettes. Normally, if there is a higher status master at the banquet, George will sit next to the right of the other master and be forced to inhale all the second hand smoke. The way it works is that there is a pecking order in which people are allowed to offer the master cigarettes. As soon as he finishes one, the next person in the chain will offer, and so on. I imagine that it would be a big deal, though invisible to an outsider, if the master accepted a cigarette out of order.Banquets are places where people are often asked to tell stories, to play music, to sing songs, or to perform feats of martial prowess like forms, breaking bricks, sticking bowls to their abdomin that can not be pulled off, breaking chopsticks on their throat, circus stuff, or even accepting friendly challenge matches. Lots of drinking happens too.

George tells me that in his travels around China he will often take martial arts masters out for lunch or dinner (a mini-preliminary-banquet). The irrepressible George Xu will often explain to a given master what he thinks the masters problems are, what mistakes the master is making in his martial training or practice. Most masters immediately try to push the table out of the way so they can test his theory with a full power fight. It is rare that they actually want to entertain the question of their own failures, or regard his challenge as an opportunity to learn. Most of the time he manages to calm them down, saying that fighting would be a waste. After all, he would be forced to fight like a wild animal and there would be no art in it. Kind of reminds me of the famous dueling scene from Akira Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai: "Ah, a tie." "No, I won!" ....

George tells me that in his travels around China he will often take martial arts masters out for lunch or dinner (a mini-preliminary-banquet). The irrepressible George Xu will often explain to a given master what he thinks the masters problems are, what mistakes the master is making in his martial training or practice. Most masters immediately try to push the table out of the way so they can test his theory with a full power fight. It is rare that they actually want to entertain the question of their own failures, or regard his challenge as an opportunity to learn. Most of the time he manages to calm them down, saying that fighting would be a waste. After all, he would be forced to fight like a wild animal and there would be no art in it. Kind of reminds me of the famous dueling scene from Akira Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai: "Ah, a tie." "No, I won!" ....Reading Chinese history, or any history for that matter, it becomes apparent that industrial commerce has created a world of food abundance which was unknown 160 years ago. Hunger was common and most people lived with food "insecurity" on a daily basis. Banquets were probably an important way of establishing confidence in the social networks which would provide food to everyone at the banquet. Each person attending a banquet represented not only themselves but lineages, ancestors, big families and many other types of social networks. These networks necessarily involved men of marital prowess who fought both to gain food resources (like land, water, livestock, money, equipment, and safe roads) and to protect the network from bandits, rebels or other types of raiders. The volatility of food resources was in constant play with wide spread violence and ever changing power dynamics. Banquets were a way of establishing patronage alliances, or mending them when they went sour.

The large size of the Chinese empire, its cities, and its wealth, required the constant mobility of men at arms. The diversity of mutually incomprehensible languages in China meant that communication was often a problem. The banquet ritual was probably a way to make sure, as we like to say, everyone was on the same page.

The large size of the Chinese empire, its cities, and its wealth, required the constant mobility of men at arms. The diversity of mutually incomprehensible languages in China meant that communication was often a problem. The banquet ritual was probably a way to make sure, as we like to say, everyone was on the same page.So, my current theory is that martial arts were an extremely important part of the banquet ritual, and the banquet ritual was widespread even among the many non-Han Chinese ethnic groups. The basic ritual involves two tables; a small one against the north wall with offerings for the ancestors, and a large table with offerings for the living. We could venture now into the realm of rituals, food offerings to the gods and to ancestors, but the subject is to big and unwieldy. Banquets are important rituals in Europe too. It's possible to over play the importance of banquets in Chinese culture and it's possible to under play them. It's also such a big subject I want to avoid saying something definitive. Most likely there is a lot of variation in practice.

So rather than stick my foot in my mouth, here is a post I wrote for Rum Soaked Fist forum about the purpose of martial arts forms:

So rather than stick my foot in my mouth, here is a post I wrote for Rum Soaked Fist forum about the purpose of martial arts forms:__________________________

Yes, forms can be used to train meditation, spacial awareness, integration, or to remember enormous amounts of kinesthetic information and...yes, a hundred other things, but it is a mistake to think those can't be trained some other way. Forms are just one way, not the only way.

The problem here is that we should be asking "How" and "When" questions more than "What" and "Why questions. The history of these arts has been intentionally corrupted and distorted. If we assume we already know "How" forms were used, then we prejudice the answers to "What" questions.

How were forms used historically? When were they performed? Given the traditional contexts in which they were used, how well did they function?

Here are some theories (yes, it's all conjecture...reality based conjecture):

1. Banquets and feasts are key Chinese religious and social institutions which were essential to creating alliances between powerful martial leaders, local officials, rebels, bandits, and other stake holders--especially in times of food insecurity. Because it was very often necessary to make alliances with people from different regions, language groups, or ethnic origins, martial arts forms (along with other demonstrations of martial prowess, singing, music, etc...) played a key roll in sealing agreements. A public exchange of forms showed a willingness to put-out and forms were thought to display "zheng," a righteous upright nature. (Calligraphy was also thought to display "zheng.")

1. Banquets and feasts are key Chinese religious and social institutions which were essential to creating alliances between powerful martial leaders, local officials, rebels, bandits, and other stake holders--especially in times of food insecurity. Because it was very often necessary to make alliances with people from different regions, language groups, or ethnic origins, martial arts forms (along with other demonstrations of martial prowess, singing, music, etc...) played a key roll in sealing agreements. A public exchange of forms showed a willingness to put-out and forms were thought to display "zheng," a righteous upright nature. (Calligraphy was also thought to display "zheng.")2. Troops were often stationed at one location for a few years, and then rotated out, back to their homes--but they were still, in a sense, "on-call." They would also gather periodically for training. It might be that having a form that you practiced with fellow troops when you were together, and then on your own, when you were at home, gave a strong sense of continuity and shared fate--essential elements of a "call-up" army. It was common for troops to be brought from disparate parts of the country where different languages were spoken--they couldn't converse as a way of bonding, so they did forms.

3. In the past, theater and exorcism were one subject. Da (hitting/fighting) is one of the five key components of theatrical training (the other four are singing, reciting history, acting, and dance). Jinghu, Chinese opera, like most if not all Chinese theater styles or jia (literally families), begins with stances (often held for an hour at a time, sometimes measured by an incense stick in the hand), the stances are then connected by transitional movements. The performer is also the conductor, unlike most western traditions, the music follows the movements (they did not need music to practice the forms). The individual aspects of the stances and movement are all taught in great detail, but every movement must be perfectly integrated into a single whole body movement with a seamless flow of qi. A theater performance is a form--identical in nearly every way to a martial arts form.

Forms are just a component of a type of theater which did not always need to be entertaining in the western sense of the word, often it was for the gods--or some other not-so-obvious purpose.

4. Whenever I go into a park early in the morning in a Chinese city, I find a spot and do my forms. If I see some people doing forms which are similar to forms I know, I do those first. If not I just keep going through my forms. Inevitably someone comes up to me and tries to figure out how I'm related to them through lineage, or if not them, someone else in the park. It's a ritual. Forms are like ID cards in China, they say...this guy is a human. It's deep stuff.

5. Forms are a good way of measuring time, before clocks they insured you were practicing a minimum amount of time.

How does ice work on injuries? Here are two contradictory opinions by experienced Sports Medicine MD's written this year within a month of each other:

How does ice work on injuries? Here are two contradictory opinions by experienced Sports Medicine MD's written this year within a month of each other: I suppose we could rank different healing methods for how close they adhere to the gold standard of, "I don't know how it works." Some are surely better than others? Ice has been a favorite of physical therapists probably from the beginning of the profession, even before there was clinical evidence. Physical therapists seem to be quite effective at getting people up and walking after surgery, but I have to wonder if they have ever done any broad based medical studies comparing ice, massage, and "exercises" to the old fashioned cattle prod. (If there was such a study you'd have to pay $25 on-line to read it--an industry wide standard which really does wonders for the prevalence of the "I don't know" factor.)

I suppose we could rank different healing methods for how close they adhere to the gold standard of, "I don't know how it works." Some are surely better than others? Ice has been a favorite of physical therapists probably from the beginning of the profession, even before there was clinical evidence. Physical therapists seem to be quite effective at getting people up and walking after surgery, but I have to wonder if they have ever done any broad based medical studies comparing ice, massage, and "exercises" to the old fashioned cattle prod. (If there was such a study you'd have to pay $25 on-line to read it--an industry wide standard which really does wonders for the prevalence of the "I don't know" factor.) In the late 1980's when I first got into thinking about Chinese medicine in relationship to martial arts, ice was thought to increase the likelihood of arthritis by creating "trapped cold" in the channels. One metaphor I remember went like this: Ice is like the Highway Patrol running a traffic break in order to clear an accident (slowing qi and blood flow). On the other hand, Chinese herbs (both topical and internal) are like opening up extra lanes for traffic to go around the accident while it is being cleared up (increasing qi and blood flow).

In the late 1980's when I first got into thinking about Chinese medicine in relationship to martial arts, ice was thought to increase the likelihood of arthritis by creating "trapped cold" in the channels. One metaphor I remember went like this: Ice is like the Highway Patrol running a traffic break in order to clear an accident (slowing qi and blood flow). On the other hand, Chinese herbs (both topical and internal) are like opening up extra lanes for traffic to go around the accident while it is being cleared up (increasing qi and blood flow). I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an  Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity).

Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity). Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead.

Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead. As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background.

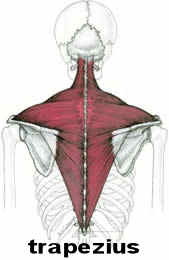

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background. Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.)

Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.) The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.

The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles. A while back I wrote a post called,

A while back I wrote a post called,  Below I have answered some questions that were sent to me via email about the post I wrote last week,

Below I have answered some questions that were sent to me via email about the post I wrote last week, I just want to say something simple about the heart. The heart needs enough space to operate.

I just want to say something simple about the heart. The heart needs enough space to operate.