Five people emailed me Ian Johnson's piece in the New York Times about Daoism Today in China,

"The Rise of Tao." It is the best article in the popular press to date about the complex role Daoism occupies in China today. I don't have much to say about it, other than

read it, but it may inspire some interesting comments below. Everything in the article was researched and fact checked beautifully, except this one observation from the author in the middle of the forth to last paragraph:

"It was physically grueling, requiring stamina and concentration."

Bad choice of words since she probably fasted for nine days before the ritual, has some neigong emptiness training, and was likely visualizing huge swaths of cosmology rather than "concentrating."

Since the New York Times is sometimes behind a pay wall I've included the whole article here:

The Rise of Tao

By IAN JOHNSON

YIN XINHUI reached the peak of Mount Yi and surveyed the chaos. The

47-year-old Taoist abbess was on a sacred mission: to consecrate a newly

rebuilt temple to one of her religion¹s most important deities, the Jade

Emperor. But there were as yet no stairs, just a muddy path up to the

pavilion, which sat on a rock outcropping 3,400 feet above a valley. A team

of workers was busy laying stone steps, while others planted sod, trees and

flowers. Inside the temple, a breeze blew through windows that were still

without glass, while red paint flecked the stone floor.

³Tomorrow,² she said slowly, calculating the logistics. ³They don¹t have

much ready. . . .² Fortunately, a dozen of her nuns had followed her up the

path. Dressed in white tunics and black trousers, their hair in topknots,

the nuns enthusiastically began unpacking everything they would need for the

next day¹s ceremony: 15 sacred scriptures, three golden crowns, three bells,

two cordless microphones, two lutes, a zither, a drum, a cymbal and a sword.

Soon the nuns were plucking and strumming with the confidence of veteran

performers. Others set up the altar and hung their temple¹s banner outside,

announcing that for the next few days, Abbess Yin¹s exacting religious

standards would hold sway on this mountain.

The temple she was to consecrate was born of more worldly concerns. Mount Yi

is in a poor part of China, and Communist Party officials had hit upon

tourism as a way to move forward. They fenced in the main mountain, built a

road to the summit and declared it a scenic park. But few tourists were

willing to pay for a chance to hike up a rocky mountain. Enter religion.

China is in the midst of a religious revival, and people will pay to visit

holy sites. So the local government set out to rebuild the temple, which was

wrecked by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution, modestly rebuilt then

torn down when the park was first constructed. Officials commissioned a

30-foot statue of the Jade Emperor, had it hauled to the peak and encased in

the brilliant red pavilion. They then built a bell and a drum tower, as well

as another set of halls devoted to minor deities.

All that was missing was a soul. For that, the temple had to be properly

consecrated. The officials got in touch with Abbess Yin, widely regarded as

a leading expert in Taoist ritual, and soon she was driving the 350 miles

from her nunnery to Mount Yi.

As her rehearsals drew to a close, the abbess went over the next day¹s

schedule with a local official. All was in good shape, he said, except for

one detail. Government officials were due to give speeches at 10:30 a.m. She

would have to be finished by then, he said.

³No,² she replied. ³Then it won¹t be authentic. It takes four hours.² Could

she start earlier and wrap up by then? No, the sun won¹t be in the right

position, she replied. The official peered up from the schedule and took a

good look at her ‹ who was this?

Abbess Yin smiled good-naturedly. At a little over five feet tall, she was

solidly built, with a full, smooth face tanned from spending much of her

life outdoors in the mountains. Her dress was always the same plain blue

robe, and she did not wear jewelry or display other signs of wealth. She

shunned electronics; her temple did not have a phone or Internet access. But

over the past 20 years she had accomplished a remarkable feat, rebuilding

her own nunnery on one of Taoism¹s most important mountains. Unlike the

temple here on Mount Yi ‹ and hundreds of others across China ‹ she had

rejected tourism as a way to pay for the reconstruction of her nunnery,

relying instead on donors who were drawn to her aura of earnest religiosity.

She knew the real value of an authentic consecration ceremony and wasn¹t

about to back down.

The official tried again, emphasizing the government¹s own rituals: ³But

they have planned to be here at 10:30. The speeches last 45 minutes, and

then they have lunch. It is a banquet. It cannot be changed.²

She smiled again and nodded her head: no. An hour later the official

returned with a proposal: the four-hour ceremony was long and tiring; what

if the abbess took a break at 10:30 and let the officials give their

speeches? They would cut ribbons for the photographers and leave for lunch,

but the real ceremony wouldn¹t end until Abbess Yin said so. She thought for

a moment and then nodded: yes.

RELIGION HAS LONG played a central role in Chinese life, but for much of the

20th century, reformers and revolutionaries saw it as a hindrance holding

the country back and a key reason for China¹s ³century of humiliation.² Now,

with three decades of prosperity under their belt ‹ the first significant

period of relative stability in more than a century ‹ the Chinese are in the

midst of a great awakening of religious belief. In cities, yuppies are

turning to Christianity. Buddhism attracts the middle class, while Taoism

has rebounded in small towns and the countryside. Islam is also on the rise,

not only in troubled minority areas but also among tens of millions

elsewhere in China.

It is impossible to miss the religious building boom, with churches, temples

and mosques dotting areas where none existed a few years ago. How many

Chinese reject the state¹s official atheism is hard to quantify, but numbers

suggest a return to widespread religious belief. In contrast to earlier

surveys that showed just 100 million believers, or less than 10 percent of

the population, a new survey shows that an estimated 300 million people

claim a faith. A broader question in another poll showed that 85 percent of

the population believes in religion or the supernatural.

Officially, religious life is closely regulated. The country has five

recognized religions: Buddhism, Islam, Taoism and Christianity, which in

China is treated as two faiths, Catholicism and Protestantism. Each of the

five has a central organization headquartered in Beijing and staffed with

officials loyal to the Communist Party. All report to the State

Administration for Religious Affairs, which in turn is under the central

government¹s State Council, or cabinet. This sort of religious control has a

long history in China. For hundreds of years, emperors sought to define

orthodox belief and appointed many senior religious leaders.

Beneath this veneer of order lies a more freewheeling and sometimes chaotic

reality. In recent months, the country has been scandalized by a Taoist

priest who performed staged miracles ‹ even though he was a top leader in

the government-run China Taoist Association. His loose interpretation of the

religion was hardly a secret: on his Web site he used to boast that he could

stay underwater for two hours without breathing. Meanwhile, the government

has made a conscious effort to open up. When technocratic Communists took

control of China in the late 1970s, they allowed temples, churches and

mosques to reopen after decades of forced closures, but Communist suspicion

about religion persisted. That has slowly been replaced by a more

laissez-faire attitude as authorities realize that most religious activity

does not threaten Communist Party rule and may in fact be something of a

buttress. In 2007, President Hu Jintao endorsed religious charities and

their usefulness in solving social problems. The central government has also

recently sponsored international conferences on Buddhism and Taoism. And

local governments have welcomed temples ‹ like the one on Mount Yi ‹ as ways

to raise money from tourism.

This does not mean that crackdowns do not take place. In 1999, the

quasi-religious sect Falun Gong was banned after it staged a 10,000-person

sit-down strike in front of the compound housing the government¹s leadership

in Beijing. That set off a year of protests that ended in scores of Falun

Gong practitioners dying in police custody and the introduction of an

overseas protest movement that continues today. In addition, where religion

and ethnicity mix, like Tibet and Xinjiang, control is tight. Unsupervised

churches continue to be closed. And for all the building and rebuilding,

there are still far fewer places of worship than when the Communists took

power in 1949 and the country had less than half the population, according

to Yang Fenggang, a Purdue University professor who studies Chinese

religion. ³The ratio is still radically imbalanced,² Yang says. ³But there¹s

now a large social space that makes it possible to believe in religion.

There¹s less problem believing.²

Taoism has closely reflected this history of decline and rebirth. The

religion is loosely based on the writings of a mythical person named Laotzu

and calls for returning to the Dao, or Tao, the mystical way that unites all

of creation. Like many religions, it encompasses a broad swath of practice,

from Laotzu¹s high philosophy to a riotous pantheon of deities: emperors,

officials, thunder gods, wealth gods and terrifying demons that punish the

wicked in ways that make Dante seem unimaginative. Although scholars once

distinguished between ³philosophical Taoism² and ³religious Taoism,² today

most see the two strains as closely related. Taoist worshipers will often go

to services on important holy days; they might also go to a temple, or hire

a clergy member to come to their home, to find help for a specific problem:

illness and death or even school exams and business meetings. Usually the

supplicant will pray to a deity, and the priest or nun will stage ceremonies

to summon the god¹s assistance. Many Taoists also engage in physical

cultivation aimed at wellness and contemplation, like qigong breathing

exercises or tai chi shadowboxing.

As China¹s only indigenous religion, Taoism¹s influence is found in

everything from calligraphy and politics to medicine and poetry. In the

sixth century, for example, Abbess Yin¹s temple was home to Tao Hongjing,

one of the founders of traditional Chinese medicine. For much of the past

two millenniums, Taoism¹s opposite has been Confucianism, the ideology of

China¹s ruling elite and the closest China has to a second homegrown

religion. Where Confucianism emphasizes moderation, harmony and social

structure, Taoism offers a refuge from society and the trap of material

success. Some rulers have tried to govern according to Taoism¹s principle of

wuwei, or nonaction, but by and large it is not strongly political and today

exhibits none of the nationalism found among, say, India¹s Hindu

fundamentalists.

During China¹s decline in the 19th and 20th centuries, Taoism also weakened.

Bombarded by foreign ideas, Chinese began to look askance at Taoism¹s

unstructured beliefs. Unlike other major world religions, it lacks a Ten

Commandments, Nicene Creed or Shahada, the Muslim statement of faith. There

is no narrative comparable to Buddhism¹s story of a prince who discovered

that desire is suffering and sets out an eightfold path to enlightenment.

And while religions like Christianity acquired cachet for their association

with lands that became rich, Taoism was pegged as a relic of China¹s

backward past.

But like other elements of traditional Chinese culture, Taoism has been

making a comeback, especially in the countryside, where its roots are

deepest and Western influence is weaker. The number of temples has risen

significantly: there are 5,000 today, up from 1,500 in 1997, according to

government officials. Beijing, which had just one functioning Taoist temple

in 2000, now has 10. The revival is not entirely an expression of piety; as

on Mount Yi, the government is much more likely to tolerate temples that

also fulfill a commercial role. For Taoists like Abbess Yin, the temptation

is to turn their temples into adjuncts of the local tourism bureau. And

private donors who have helped make the revival possible may also face a

difficult choice: support religion or support the state.

Zhengzhou is one of China¹s grittiest cities. An urban sprawl of 4.5

million, it owes its existence to the intersection of two railway lines and

is now one of the country¹s most important transport hubs. The south side is

given over to furniture warehouses and markets for home furnishings and

construction materials. One of the biggest markets is the five-story Phoenix

City, with more than four million square feet of showrooms featuring real

and knockoff Italian marble countertops, German faucets and American lawn

furniture. Living in splendor on the roof of this mall like a hermit atop a

mountain is one of China¹s most dynamic and reclusive Taoist patrons, Zhu

Tieyu.

Zhu is a short, wiry man of 50 who says he once threw a man off a bridge for

the equivalent of five cents. ³He owed me the money,² he recalled during a

nighttime walk on the roof of Phoenix City. ³And I did anything for money:

bought anything, sold anything, dared to do anything.² But as he got older,

he began to think more about growing up in the countryside and the rules

that people lived by there. His mother, he said, deeply influenced him. She

was uneducated but tried to follow Taoist precepts. ³Taoist culture is

noncompetitive and nonhurting of other people,² he says. ³It teaches

following the rules of nature.²

Once he started to pattern his life on Taoism, he says, he began to rise

quickly in the business world. He says that by following his instincts and

not forcing things ‹ by knowing how to be patient and bide his time ‹ he was

able to excel. Besides Phoenix City, he now owns large tracts of land where

he is developing office towers and apartment blocks. Although he is reticent

to discuss his wealth or business operations, local news media say his

company is worth more than $100 million and have crowned him ³the king of

building materials.² Articles almost invariably emphasize another aspect of

Zhu: his eccentric behavior.

That comes from how he chooses to spend his wealth. Instead of buying

imported German luxury cars or rare French wines, he has spent a large chunk

of his fortune on Taoism. The roof of Phoenix City is now a

200,000-square-foot Taoist retreat, a complex of pine wood cabins, potted

fruit trees and vine-covered trellises. It boasts a library, guesthouses and

offices for a dozen full-time scholars, researchers and staff. His Henan

Xinshan Taoist Culture Propagation Company has organized forums to discuss

Taoism and backed efforts at rebuilding the religion¹s philosophical side.

He says he has spent $30 million on Taoist causes, a number that is hard to

verify but plausible given the scope of his projects, including an office in

Beijing and sponsorship of international conferences. His goal, he says, is

to bring the philosophical grounding of his rural childhood into modern-day

China.

Last year, Zhu invited several dozen European and North American scholars of

Chinese religion on an all-expenses-paid trip to participate in a conference

in Beijing. The group stayed in the luxurious China World Hotel and were

bused to Henan province to visit Taoist sites. Demonstrating his political

and financial muscle, Zhu arranged for the conference¹s opening session to

be held in Beijing¹s Great Hall of the People, the Stalinesque conference

center on Tiananmen Square. It is usually reserved for state events, but

with the right connections and for the right price, it can be rented for

private galas. In a taped address to participants, Zhu boasted that ³I¹ll

spend any amount of money² on Taoism.

Zhu¹s chief adviser, Li Jinkang, says the goal is to keep Taoism vital in an

era when indigenous Chinese ideas are on the defensive. ³Churches are

everywhere. But traditional things are less so. So Chairman Zhu said: ŒWhat

about our Taoism? Our Taoism is a really deep thing. If we don¹t protect it,

then what?¹ ²

Balancing this desire with the imperatives of China¹s political system is

tricky. While the Communist Party has allowed religious groups to rebuild

temples and proselytize, its own members are supposed to be good Marxists

and shun religion. Like many big-business people, Zhu is also a party

member. Two years ago, he became one of the first private business owners to

set up a party branch in his company, earning him praise in the pages of the

Communist Party¹s official organ, People¹s Daily. He has also established a

party ³school² ‹ an indoctrination center for employees. His company¹s Web

site has a section extolling his party-building efforts and has a meeting

room with a picture of Mao Zedong looking down from the wall. Although it

might seem like an odd way to mix religion and politics, Taoism often

deifies famous people; at least three Taoist temples in one part of China

are dedicated to Chairman Mao.

Until recently, Zhu mostly ignored the contradiction, but he has become more

cautious, emphasizing how he loved Taoist philosophy and playing down the

religion. Still, Zhu continues to support conventional Taoism. His staff

takes courses in a Taoist form of meditation called neigong, and he has sent

staff members to document religious sites, like the supposed birthplace of

Laotzu, who is worshiped as a god in Taoism. He also has close relations

with folk-religious figures and plans to establish a ³Taoist base² in the

countryside to propagate Taoism. ³The ancients were amazing,² Zhu says.

³Taoism can save the world.²

WHEN ABBESS YIN started to rebuild her nunnery in 1991, she faced serious

challenges. Her temple was located on Mount Mao, among low mountains and

hills outside the eastern metropolis of Nanjing. It had been a center of

Taoism from the fourth century until 1938, when Japanese troops burned some

of the temple complex. As on Mount Yi, communist zealots completed the

destruction in the 1960s. Her temple was so badly damaged that the forest

reclaimed the land and only a few stones from the foundation could be found

in the underbrush.

Unlike Mount Yi, Mount Mao is an extensive complex: six large temples with,

altogether, about 100 priests and nuns. Just a 45-minute drive from Nanjing

and two hours from Shanghai, it is a popular destination for day-trippers

wanting to get out of the city. Even 20 years ago, when Abbess Yin arrived,

tourism-fueled reconstruction was in full swing on Mount Mao. Two temples

had escaped complete destruction, and priests began repairing them in the

1980s. The local government started charging admission, taking half the gate

receipts. But the Taoists still got their share and plowed money back into

reconstruction. More buildings meant higher ticket prices and more

construction, a cycle typical of many religious sites. Although pilgrims

began to avoid the temples because of the overt commercialism, tourists

started to arrive in droves, bused in by tour companies that also got a cut

of gate receipts. Last year, ticket sales topped $2.7 million.

Abbess Yin opted for another model. Trained in Taoist music, she set up a

Taoist music troupe that toured the Yangtze River delta in a rickety old

bus, stopping at communities that hired them to perform religious rituals.

When I first met her in 1998, she used the money to rebuild one prayer hall

on Mount Mao but refused to charge admission. Word of her seriousness began

to spread around the region and abroad. Soon, her band of nuns were

performing in Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

More nuns began to join. In the Quanzhen school of Taoism, which Abbess Yi

follows, Taoist clergy members live celibate lives in monasteries and

nunneries, often in the mountains. (In the other school, known as Zhengyi,

they may marry and tend to live at home, making house calls to perform

ceremonies.) For Abbess Yin¹s young nuns, her temple provided security and

calm in a world that is increasingly complicated. ³Here, I can participate

in something profound,² said one nun who asked to be identified only as

Taoist Huang. ³The outside world has nothing like this.² For Abbess Yin, the

young people are a chance to mold Taoists in the image of her master. ³The

only people who are worth having are older than 80 or younger than 20.²

Even now, Abbess Yin¹s temple is low-key. There are no tourist attractions

like cable cars, gift shops, teahouses or floodlit caves ‹ and, unlike at

most temples, still no admission fee. The atmosphere is also different.

While in some temples, priests seem to spend most of their time hawking

incense sticks or offering to tell people¹s fortunes, her nuns are quiet and

demure. Maybe this is why even in the 1990s, when her temple was reachable

only by a dirt road, locals said it was ling ‹ that it had spirit and was

effective. In 1998, I saw a group of Taiwanese visitors abandon their bus

and walk two miles to the temple so they could pray. ³This is authentic,²

one told me. ³The nuns are real nuns, and it¹s not just for show.²

With a growing reputation came donations. One reason that city people often

underestimate Taoism is that its temples are mostly in the mountains, and

its supporters rarely want to discuss their gifts. But one way to gauge its

support is to look at the lists of benefactors, which are carved on stone

tablets and set up in the back of the temple. In Abbess Yin¹s temple, some

tablets record 100,000 yuan ($15,000) donations, while others show 10,000

yuan gifts. But even those making just 100 yuan contributions get their

names in stone. With the donations came the current plan to build the $1.5

million Jade Emperor Hall halfway up the mountain, making the Mount Mao

complex visible for miles around. It is due to open on this weekend, with

Taoists from Southeast Asia and across China expected to participate.

Abbess Yin¹s success led the China Taoist Association to invite her to

Beijing for training. She learned accounting, modern management methods and

the government¹s religious policy. Earlier this year she was placed on one

of the association¹s senior leadership councils. She has also begun speaking

out on abuses on the religious scene, urging greater strictness inside

Taoist temples and less emphasis on commerce. Many Taoists, she wrote in an

essay reprinted in an influential volume, have become obsessed with making

money and aren¹t performing real religious services but just selling

incense. Too many traveled around China, using temples as youth hostels

instead of as places to study the Tao or to worship.

³Taoism is a great tradition, but our problem is we¹ve had very fast growth,

and the quality of priests is too low,² she told me. ³Some people don¹t even

know the basics of Taoism but treat it like a business. This isn¹t good in

the long-term.²

THE DAY AFTER Abbess Yin¹s standoff with the official, the big event on

Mount Yi was due to start. She arrived early, making sure her nuns were

ready at 7. The muddy path was now covered with stones that farmers had just

hosed down, making them glisten in the early-morning sun. Workers scraped

paint off the floor, inflated balloons and hung banners, while a television

crew set up its equipment to film the politicians.

Inside the Jade Emperor Pavilion, the nuns milled around, checking one

another¹s clothes and hair. All, including the abbess, were wearing their

white tunics and black knee breeches. They pulled on fresh blue robes and

pink capes, while the abbess donned a brilliant red gown with a blue and

white dragon embroidered on the back. She and her top two lieutenants

affixed small golden crowns to their topknots. She was now transformed into

a fashi, or ritual master. Something was about to happen.

Abbess Yin walked over to a drum about two feet in diameter and picked up

two wooden sticks lying on top. She began pounding in alternating rhythms.

The nuns knew their roles by heart and lined up in two rows, flanking the

statue of the Jade Emperor, golden and beautiful, the god¹s eyes beatific

slits and his mouth slightly parted as if speaking to the people below.

Still, for now the statue was just a block of wood. The ceremony would

change that. It is called kai guang or ³opening the eyes² ‹ literally,

opening brightness. Abbess Yin could open them, but it would take time.

Five minutes passed and sweat glistened on her forehead. Then, six of the

nuns quietly took their places and started to play their instruments. A

young woman plucked the zither, while another strummed the Chinese lute, or

pipa. Another picked up small chimes that she began tinkling, while a nun

next to her wielded a cymbal that she would use to punctuate the ceremony

with crashes and hisses. Abbess Yin stopped drumming and began to sing in a

high-pitched voice that sounded like something out of Peking Opera. Later

during the ceremony she read and sang, sometimes alone and at other times

with the nuns backing her. Always she was in motion: kneeling, standing,

moving backward, turning and twirling, the dragon on her back seeming to

come alive. It was physically grueling, requiring stamina and concentration.

During the occasional lull, a young nun would hand her a cup of tea that she

delicately shielded behind the sleeve of her robe and drank quickly.

Gradually, people began to pay attention. The wives of several officials

stood next to the altar and gawked, first in astonishment and then with

growing respect for the intensity of the performance. When a police officer

suggested they move back, they said: ³No, no, we won¹t be a bother. Please,

we have to see it.² Workers, their jobs finished, sat at the back. Within an

hour, about 50 onlookers had filled the prayer hall.

On cue, at 10:30, she stopped. A group of local leaders had assembled

outside the hall. They announced the importance of the project and how they

were promoting traditional culture. A ribbon was cut, applause sounded and

television cameras whirred. Then the group piled into minibuses and rolled

down to the valley for the hotel lunch.

The speeches were barely over when Abbess Yin picked up again. As the

ceremony reached its climax, more and more people began to appear, seemingly

out of nowhere, on the barren mountain face. Four policemen tried to keep

order, linking arms to barricade the door so the nuns would have space for

the ceremony. ³Back, back, give the nuns room,² one officer said as the

crowd pressed forward. People peered through windows or waited outside,

holding cameras up high to snap pictures. ³The Jade Emperor,² an old woman

said, laying down a basket of apples as an offering. ³Our temple is back.²

Abbess Yin moved in front of the statue, praying, singing and kowtowing.

This is the essence of the ritual ‹ to create a holy space and summon the

gods to the here and now, to this place at this moment.

Shortly after noon, when it seemed she had little strength left, Abbess Yin

stopped singing. She held a writing brush in one hand and wrote a talismanic

symbol in the air. Then she looked up: the sun was at the right point,

slanting down into the prayer room. This was the time. She held out a small

square mirror and deflected a sunbeam, which danced on the Jade Emperor¹s

forehead. The abbess adjusted the mirror slightly and the light hit the

god¹s eyes. Kai guang, opening brightness. The god¹s eyes were open to the

world below: the abbess, the worshipers and the vast expanse of the North

China Plain, with its millions of people racing toward modern China¹s

elusive goals ‹ prosperity, wealth, happiness.

Ian Johnson is the author of ³A Mosque in Munich² and ³Wild Grass: Three

Stories of Change in Modern China.² He is based in Beijing.

November 5, 2010

Copyright 2010 The New York Times

Tanka

Tanka

Being baby-like is used as a metaphor to describe the Dao in several key chapters of the Daodejing. I've ventured into this particular play-pen many times before, but each time I see things differently.

Being baby-like is used as a metaphor to describe the Dao in several key chapters of the Daodejing. I've ventured into this particular play-pen many times before, but each time I see things differently. But children often have some difficulty distinguishing what is real from what is imaginary. It's easy to see how this might come about, especially if most of what we think we are "seeing" is actually being organized by our imagination. We usually see ghosts out of the corner of our eyes. Magicians use 'slight of hand' which basically means they get you to focus one way and imagine the other. When someone shouts in a crowd, "He's got a knife!" lots of people will be certain they saw it, even if it never existed.

But children often have some difficulty distinguishing what is real from what is imaginary. It's easy to see how this might come about, especially if most of what we think we are "seeing" is actually being organized by our imagination. We usually see ghosts out of the corner of our eyes. Magicians use 'slight of hand' which basically means they get you to focus one way and imagine the other. When someone shouts in a crowd, "He's got a knife!" lots of people will be certain they saw it, even if it never existed. The paper was sent to me because I told someone I thought the idea of reflexes was a bit flimsy. The paper offers evidence to counter the idea that babies have reflexes. The "rooting" reflex used by babies to find their mothers breast seems to turn off after they have eaten! And the "sucking" reflex is very dynamic. Babies adjust how much they are sucking moment to moment depending on how much milk is available. They also change their sucking patterns in order to get their mother's to vocalize. In other words, babies are in control!

The paper was sent to me because I told someone I thought the idea of reflexes was a bit flimsy. The paper offers evidence to counter the idea that babies have reflexes. The "rooting" reflex used by babies to find their mothers breast seems to turn off after they have eaten! And the "sucking" reflex is very dynamic. Babies adjust how much they are sucking moment to moment depending on how much milk is available. They also change their sucking patterns in order to get their mother's to vocalize. In other words, babies are in control! One of the things I love about teaching beginners is that they ask the most basic and obvious questions, and I get stumped.

One of the things I love about teaching beginners is that they ask the most basic and obvious questions, and I get stumped.

And thus I have a theory.

And thus I have a theory.

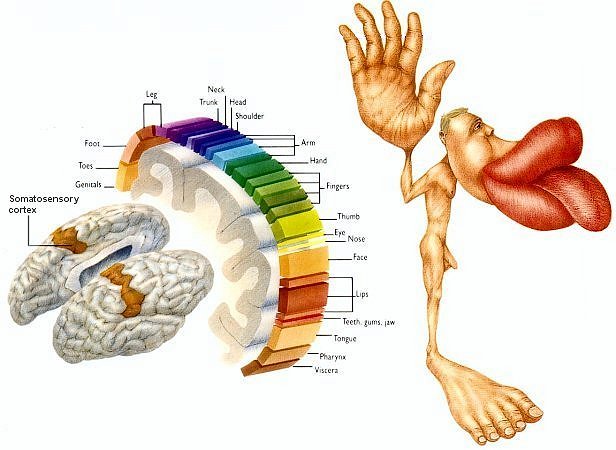

They say we use only a small portion of our brain, and that of the small part we do use, about

They say we use only a small portion of our brain, and that of the small part we do use, about

If I understand it correctly, Chinese religious custom thinks of negative influences from the dead as ghosts, and positive influences as ancestors. But the principle is the same, and if we could transcend the taboo I suspect it would also be obvious that some positive lingering influence comes from outside the family and some negative influence comes from our direct ancestors.

If I understand it correctly, Chinese religious custom thinks of negative influences from the dead as ghosts, and positive influences as ancestors. But the principle is the same, and if we could transcend the taboo I suspect it would also be obvious that some positive lingering influence comes from outside the family and some negative influence comes from our direct ancestors.

Michael Saso has his own

Michael Saso has his own