The Whirling Circles of Ba Gua Zhang (last chapter)

/ The last chapter of The Whirling Circles of Ba Gua Zhang, is titled "A Moving Yi Jing." The meat and potatoes of this chapter are two great lists.

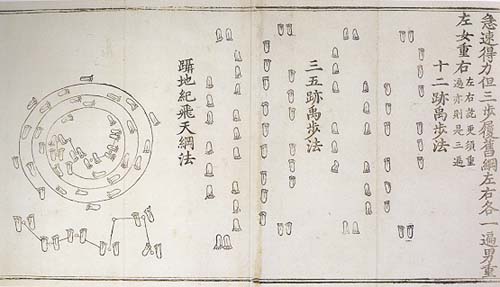

The last chapter of The Whirling Circles of Ba Gua Zhang, is titled "A Moving Yi Jing." The meat and potatoes of this chapter are two great lists.The first list is a paragraph for each of the qi transmissions associated with each of the eight "mother palms" and gua (trigrams) of B.K. Frantzis's baguazhang system (which has no form).

The qi transmissions are supplemented in the applications section too. The authors clearly and succinctly describe the feeling of each palm change; how it moves and what makes it distinct. They also explain that the best way to develop these qi transmissions is through the practice of Soft-hands, Roshou (a dynamic moving and slapping version of push-hands).

I plan to do a video for each of the Baguazhang qi transmissions with in a year.

What is a Daoist Body?Â

The second list is this:

- The Physical Body

- The Qi Body

- The Emotional Body

- The Thinking Body

- The Psychic Body

- The Causal Body

- The Body of Individuality

- The body of the Dao

The authors give very short descriptions of what each category might mean, calling them energy bodies. Beyond that what they say is embarrassing for it's lack of connection to anything real. (Baguazhang is not a self-help program, and neither is the Yijing.)

Religious Daoism conceptualizes a human being as not just one body but many bodies. Calling them "energy bodies" is misleading. Your house is a body that you share with everyone else who lives there. You can clean, remodel, or move to another house, but the fact that you have such a body is a given. All bodies relate to other bodies. If you live in a damp shack for a month your physical body will start to creek at the joints and your lung capacity will decrease (effecting your qi body).

The way religious Daoists conceptualize it, we share a body with everyone who reads this blog or speaks English. More importantly, we share a body with everyone who makes the same commitments we do, thus Christians all share a body, Muslims all share a body, and everyone who worships Guanyin shares a body.

Ghosts have very weak bodies, demons and gods very strong ones (we give them our strength).

Horror movies are so visceral because as you watch them your various "commitment bodies" are being contorted, poked and exploded. (Obviously, I love the horror genre.)

This is a list used to train Daoist exorcists. In order to do an exorcism you must be able to recognize all the different types of possession in other people and in yourself.

- Physical possession is pain. In it's lesser forms we recognize it as tension or even "strength." Physical possession causes people to lash out and to blame.

- Qi possession is associated with controlling the breath, it amplifies feelings, creates excitement and it can lead to transcendent states. (Godlike or "I can't feel my body" types of disassociation.) Mania.

- Emotional possession translates perfectly into English. Possessed by fear, anger, love, etc...

- Thinking possession is like believing that the oceans are going to rise because we drive to work. Or that everything that happens in the Middle-East matters. You know, "Global Conspiracy," "The world is in crisis, dude."

- Psychic possession is believing you know what someone else is thinking, or what is about to happen next.

- Causal possession is like schizophrenia. When you think objects or icons or voices in your head are the cause of something in the real world. Profound disassociation.

- The body of Individuation is supreme ego-mania. There are a number of narcotics that can bring about this near-death experience. It is when you feel/believe that you are the cause and purpose of everything.

- The body of the Dao is a complete death. Sometimes call immortality. It is experience without any limits or conceptions.

Baguazhang is a dance form that explores all the different ways we can become possessed. It is dancing with what it is to be alive. Perhaps we could think of it as a personal, daily exorcism, although that certianly isn't traditional.

In case I lost you-- and you don't see the connection to martial arts-- notice that I just made a really good list of what might cause someone to attack you.

Here I continue my commentary on The

Here I continue my commentary on The  If you haven't read Yang-Chu, I recommend it. Yang-Chu is considered one of the early voices of Daoism (300 BCE), a voice for wuwei.

If you haven't read Yang-Chu, I recommend it. Yang-Chu is considered one of the early voices of Daoism (300 BCE), a voice for wuwei. first heard this I was in shock for a few days. Why was I bothering with all the little details, like doing the dishes and "communicating" if almost all the significant data was in a 15 minute video interview? Is it possible that we really don't have free will?

first heard this I was in shock for a few days. Why was I bothering with all the little details, like doing the dishes and "communicating" if almost all the significant data was in a 15 minute video interview? Is it possible that we really don't have free will? At the end of summer Daoists eat foods which cool blood to release any trapped summer heat before starting the tonification process leading into winter. This bean-thread noodle recipe by Daoist priest

At the end of summer Daoists eat foods which cool blood to release any trapped summer heat before starting the tonification process leading into winter. This bean-thread noodle recipe by Daoist priest  boiling water for 30 seconds

boiling water for 30 seconds The ninth precept, yielding to others, is wuwei. The first precept probably works better in English as "Be Honest." The second precept is often the tough one for people. The flexibility part sounds cool, but the weakness part is confusing. Here is what

The ninth precept, yielding to others, is wuwei. The first precept probably works better in English as "Be Honest." The second precept is often the tough one for people. The flexibility part sounds cool, but the weakness part is confusing. Here is what  The reason for discipline is to make a practice irreversible.

The reason for discipline is to make a practice irreversible. For example, the Kitchen God lives over the stove in Chinese homes. He represents an irreversible commitment to keep the house clean. The method is cleaning on a regular schedule. When cleaning becomes "second nature" the method can become more spontaneous, but it can't really be dropped. The fruition is living in a cleaner, simpler, healthier environment, where things are easy to find, easy to store, and easy to get rid of.

For example, the Kitchen God lives over the stove in Chinese homes. He represents an irreversible commitment to keep the house clean. The method is cleaning on a regular schedule. When cleaning becomes "second nature" the method can become more spontaneous, but it can't really be dropped. The fruition is living in a cleaner, simpler, healthier environment, where things are easy to find, easy to store, and easy to get rid of. Most Daoist inspired methods reveal something about your true nature. Often it is an appetite of some kind. The most obvious example is that sitting or standing practices reveal an appetite for stillness. After about two years of discipline your appetite should be strong enough to direct your practice, rigid or militaristic discipline will actually hold you back. I know my morning standing practice is irreversible because if some anomaly or emergency disrupts my practice, the rest of the day I feel myself being pulled toward stillness--At the end of the day I jump into bed and savor the thought of waking up to my practice.

Most Daoist inspired methods reveal something about your true nature. Often it is an appetite of some kind. The most obvious example is that sitting or standing practices reveal an appetite for stillness. After about two years of discipline your appetite should be strong enough to direct your practice, rigid or militaristic discipline will actually hold you back. I know my morning standing practice is irreversible because if some anomaly or emergency disrupts my practice, the rest of the day I feel myself being pulled toward stillness--At the end of the day I jump into bed and savor the thought of waking up to my practice.

I just wrote a long response to José de Freitas whose comment at the end of the

I just wrote a long response to José de Freitas whose comment at the end of the