Continuing my discussion of the

Whirling Circles of Ba Gua Zhang, by Frank Allen and Tina Chunna Zhang, we turn to the chapter entitled "The Daoist Roots of Baguazhang."

The chapter can be summarized like this: Dong Haichuan and Liu Hung Chieh both studied with some unnamed Daoists and Daoists do meditation. Baguazhang practitioners do sitting, standing, and walking meditation, which must have come from these unnamed Daoists. See the problem yet?

In the second paragraph we read:

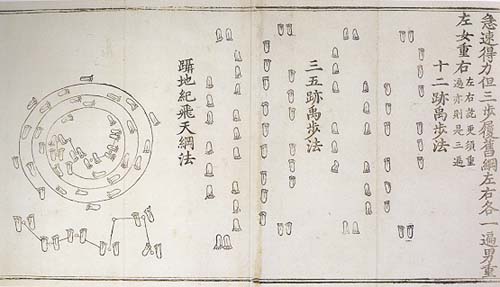

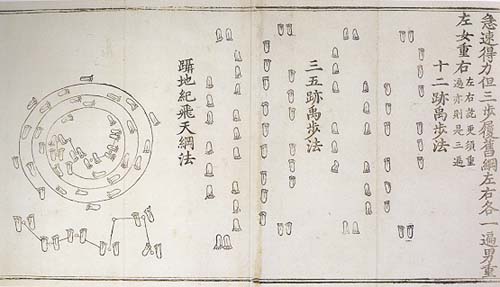

Apparently, these Daosits looked to their predecessors--the shaman founders of Chinese culture--for some of the patterns of their moving meditations. Some of the oldest texts relating to the study of the Dao have chronicled a few of the dance patterns of the legendary Yu, mythical father of Chinese Shamanism. The patterns of many of these Shamanistic practices were circles and spirals.

The connection of the Dance of Yu to baguazhang is one of those big multi-layered topics for another day. But I can at least point out what the authors don't; Da Yu (the Great Yu) was an exorcist. The reason he is considered the founder of Chinese culture is because 4000 years ago he toured the known world (the whole country) performing the first national exorcisms.

I grew up around a lot of Cantonese speaking kids. When they got mad they would shout "Fuk Da Yu!" which sounded

so much like F--k Y-u! that we had a lot of fun saying it. It turns out that they were saying "A curse upon your ancestors." Yu is the mythic ancestor of all Chinese and his name has actually come to mean "ancestor!"

The authors present Professor Kang Gewu's thesis that the roots of baguazhang are to be found in a circle walking practice of the Longmen sect. The concept of "secularism" does not translate very well into Chinese. For instance, Catholicism and Protestantism have often been viewed by Chinese as completely different religions. The idea that Daoism has sects is foreign to Daoism itself. This notion adds somewhat to the confusion about baguazhang's daoist roots. If it's possible to be ordained in a

Quanzhen monastery, go and study ritual with a

Tianshi householder, and then go live in a

Zhengyi hermit enclave on Mao Mountain--then these

categories don't meet the definition of sects.

To the authors credit, Longmen (Dragon gate) is correctly identified as a later Daoist lineage (1656) of the Qing Dynasty which merged with Confucianism and promoted a public code of conduct for lay practitioners. (I think of it as decaf-Daoism. It would be very hard to figure out why people drink coffee everyday if the only kind you had ever tried was decaf.)

That's most of what the authors have to say about Daoism. At one point they describe the meditative

goal of circle walking as, to "make heaven and earth reside within one's own body," thus joining our inner world with the outer world to become "One with the Dao." Thanks for that. Basic Chinese cosmology posits that we are a temporary contract between Heaven and Earth to hang out in a body for, give or take, 80 years. How does walking in a circle make that more or less true?

In the second half of this chapter, the authors describe in detail a method of "dissolving" taught by B.K. Frantzis.

The method described here is great. The problem is that without contextualization, without some grasp of the view which inspired this method, there is a very high probability that the fruition of practice will be overlooked. (And that appears to be what happened.)

The method they describe has the goal of clearing "energy blockages" from the body so that we can store unlimited amounts of qi. I'm deeply familiar with this method but I don't personally like to think of myself as being full of energy blockages, whatever that means. Frankly, the method is not very important.

My intension is not to sound dismissive, by all means, clear out those energy blocks! But taking a step back, isn't that what I am--

a big old energy blockage. To all my fellow energy blockages out there (this means you, dear reader) I say this: Respect yourself, lighten up, and trust your experience. You'll figure it out.

Buy it From Amazon

In Japanese, which uses Chinese written characters, Dao becomes "do," in many familiar arts like Karatedo, Judo, Aikido, Budo (the warrior code), and Chado (the art of tea).

In Japanese, which uses Chinese written characters, Dao becomes "do," in many familiar arts like Karatedo, Judo, Aikido, Budo (the warrior code), and Chado (the art of tea).

Healing by Commitment

Healing by Commitment On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on

On Saturday I made it to the last session of this conference on  it seems like a good time to link to my own "

it seems like a good time to link to my own "

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism.

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism. The last chapter of

The last chapter of

Here I continue my commentary on The

Here I continue my commentary on The  If you haven't read Yang-Chu, I recommend it. Yang-Chu is considered one of the early voices of Daoism (300 BCE), a voice for wuwei.

If you haven't read Yang-Chu, I recommend it. Yang-Chu is considered one of the early voices of Daoism (300 BCE), a voice for wuwei. first heard this I was in shock for a few days. Why was I bothering with all the little details, like doing the dishes and "communicating" if almost all the significant data was in a 15 minute video interview? Is it possible that we really don't have free will?

first heard this I was in shock for a few days. Why was I bothering with all the little details, like doing the dishes and "communicating" if almost all the significant data was in a 15 minute video interview? Is it possible that we really don't have free will? I've been teaching children for 20 years. In my opinion, there is no such thing as shyness. I believe it is possible that there is some type of mental illness which manifests as shyness; but for the most part what teachers call shyness falls into two categories: Reluctant deadbeats and indolent wannabe royalty.

I've been teaching children for 20 years. In my opinion, there is no such thing as shyness. I believe it is possible that there is some type of mental illness which manifests as shyness; but for the most part what teachers call shyness falls into two categories: Reluctant deadbeats and indolent wannabe royalty. classmates. They may even fear adults.

classmates. They may even fear adults. afraid to speak. In that case pretend that they gestured with their eyes at some other student who wasn't looking and call that student up. If they are a true queen they will become indignant and declare that they did not, and would not have made such a choice. You have won. Now all the other students know they are not shy.

afraid to speak. In that case pretend that they gestured with their eyes at some other student who wasn't looking and call that student up. If they are a true queen they will become indignant and declare that they did not, and would not have made such a choice. You have won. Now all the other students know they are not shy.