Applications, Not

/

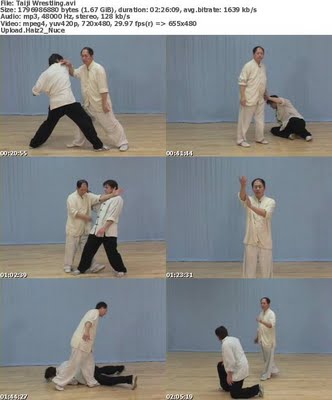

I've been suspicious of apps since before I ever started teaching, my first teacher, Bing, didn't teach apps. (Martial applications have become such a standard part of martial arts curriculum that people often refer to them simply as "apps" for sort.)

It is fascinating that apps have taken over. If I had to bet, I wouldn't put the blame on teachers, aggressive students demand apps! And teachers are probably seduced by the role of being the candy man--'hey, dude, they are paying me to keep them at a low level of learning --how can I say no?'

George Xu did teach us applications, but his theory at the time (and back then we had a lot of time...4 hours a day, 6 days a week) was that the student should have at least three applications for every inch of movement. And after a while, the student will develop disdain for all technique and move on to a level of practice where any and all movement is an infinity of open possibilities.

After reaching that level, apps seem silly, 'though, as collectors, we might occasionally be stimulated by a novel or creative app.

But students love apps. They're always askin' for them. George Xu explained to us that in and around those dark days of the Cultural Revolution, if a person was unwise enough to asked his xinyi teacher about an app, the student would for sure walk home bloodied. George told us this casually, but years later when his brother Gordon Xu came over to the States I asked him about George's xinyi teacher and he was like, 'Oh that guy was treturous, the skin on George's shins never had time to grow back.'

In the past, I have sometimes given in to my student's requests to teach them apps, and have lamented that iphones and microwaves have given us neither more free time nor a stronger sense of commitment.

But putting all that aside, enlightened-genius-former-jail-guard Rory Miller solved this problem for me! He articulated a point which, the moment I heard it, stopped my heart. "What? Oh my gosh, it's so obvious, how is it that no one articulated this to me before?" The insight is that we fight to established martial stances, not from them. Once a student knows the given stance I can put them-- or myself-- in a seriously compromised I've just been surprise attacked position and from there, fight to the stance. This allows me to point out, or for the student to spontaneously discover, target options, angle variations, or changes in orientation. This way the information goes into the correct part of the brain without becoming a technique to remember or forget, and it doesn't inhibit learning. Good angles are good angles, vulnerable targets are vulnerable targets, there is no good reason to link them to particular movements.

Since surprise attacks tend to leave people disoriented, it seems important to practice fighting from disorientation.