Literature as Ritual Combat

/Mark R. E. Meulenbeld’s new book Demonic Warfare: Daoism, Territorial Networks, and the History of a Ming Novel, is a wonderful new book that starts out with a problem. Historical shifts in perception have obscured the subject he is studying by dividing it up into different fields. In order to make the subject whole in reader’s minds requires a metaphor, like a series of bridges, or linkages, or an estranged family getting back together. But none of these are up to the task. The metaphor would need to explain that a thing that was once whole, was mis-perceived for a hundred years as being separate categories and yet it always was and remains whole. Is there a metaphor that easily does that?

His subject is Chinese literature, Daoist religion, and local combat networks. His assumption is that theatrical-martial-ritual texts, religious organization, and warfare were a single subject.

The case that Meulenbeld makes is quite similar to the case I have been making on this blog and in other writing, namely that Chinese martial arts, religion and theater were a single subject. The major difference is that the basis of his realization comes largely from studying texts, while mine comes out of somatic experience. The two notions fit together like a whole that was never separate (I don’t have an adequate metaphor either).

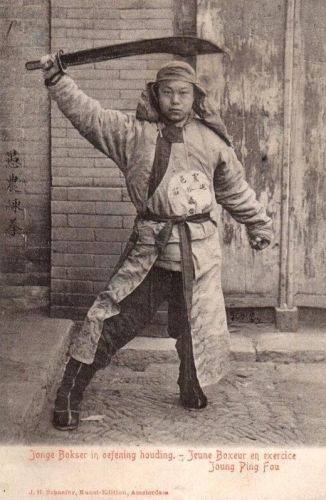

Meulenbeld begins by showing that the category of literature in China is a modern invention. Martial-ritual-theatrical texts were transformed into literature via a process of ridicule and dismissiveness. Religion in these texts was seen as humiliating to the modernizers of the early 20th Century who were grappling with the symbolic defeat of the Boxer Rebellion, the end of foot-binding, and the desire to shrug off the “Sick Man of Asia” label. What happened to literature is akin to what happened to Daoism, theater, and of course martial arts.

[I highly recommend these books for discussions of the invention of these modern subjects, Daoist Modern , Chinese Theatre

, Martial Arts

, and History

itself.]

Lu Xun, leading intellectual of the May 4th movement, considered “Daoist fiction” both a fabrication and a deceit! This sort of activist conceit is still very much alive in the Western discourses on martial arts and literature. As a modernist protest, it is even more desperate in the Chinese discourses.

As the 20th Century progressed, the situation just got worse. Important texts of ritual martial theater got ignored, the few that did get attention were pounded into a secular mold. This was a process led by Chinese, even if we can see the impulse for it in Protestant Christianity. Protestantism was spread in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s through the building of hospitals and schools, and by preaching feminism and rationality. It is a dark irony that the secular impulse within China is in fact Protestant inspired revisioning.

The vernacular Chinese fictional works most readers will be familiar with are Journey to the West (Monkey King), The Three Kingdoms, and Outlaws of the Marsh. That is because these three works were the easiest to transition to the modern notion of literature. But in the late Imperial period there were a number of other works that were equally important but which have become obscure through dismissiveness and ridicule, the ritual elements in these works were just too obvious. Meulenbeld focuses on one work of ritual martial arts fiction called Canonization of the Gods, Fengshen yanyi.

Anyone who reads one of these so called novels in English discovers that they are collections of awkwardly connected stories with too many characters, just barely held together by larger themes. However, once we understand that they were built or assembled from theatrical rituals of canonization, the logic of their organization becomes coherent. Demonic Warfare is a landmark work and will no doubt spawn new translations of China’s epic fiction informed by an understanding of the cultural context which created these works.

Theatrical presentations of these works are always short stories, individual chapters as it were. Hundreds of these chapters work as stage theater but contemporary imaginations tend to find them structurally complicated. The magical abilities that many key characters have, and the transformations they go through, contain layers of metaphor and presumptions of cosmological knowledge that are not explicated in the individual stories. In other words, they are rituals of social organization first, and cosmological teaching stories second. The substantial entertainment value they once had was built around their value as cultural pivots of meaning.

After reviewing the enormous hostility towards religion which framed the discourses of the 20th Century, Meulenbeld shows how Chinese literature grew out of the ritual theatricality of temple culture(s). Temples were intertwined organizational networks, they were the primary institution used to organize militias and other forms of organized, sanctioned violence.

Martial rituals functioned by infusing and imbuing would be combatants with an active cosmology of ritual actions which gave meaning to violent struggles in historic time and regional locale.

While Demonic Warfare does not discuss embodied martial arts directly, it is a collection of ideas and insights that will have martial artists rolling on the floor with delight. It brings us a lot closer to an understanding of what Chinese martial arts are, and where they came from.

Given the insights from this book, martial arts can be understood as the embodied shell of canonization rituals that were done to contextualize violence, rituals that were scalable for both small and large group warfare.

Meulenbeld translates the key term feng 封 from the title of Canonization of the Gods (Fengshen yanyi), as “canonization.” There is an implicit parallel here with Catholicism. Martyrs are people who died premature deaths, people who have been credited with transcendent values and purpose. A martyr dies for a cause, usually a noble, virtuous or valiant one. Canonization is the process of promoting a martyr to sainthood so that he or she can be looked to for comfort or strength. It was used extensively by the Catholic hierarchy to incorporate the fringes of its control into a network of reciprocity. For instance a great many of the Haitian gods of Voodoo are also Catholic saints, they just changed the names. The basic formula works for Chinese warfare too, conquer your enemies and then turn their local gods and heros into righteous demon warriors and saints in your heavenly hierarchy established by regular theatrical rituals and regulated by a hierarchy of ritual experts.

When they wanted a local militia to hook up with other local militias under a military command structure they performed rituals which imagined collections of local gods and demons fighting for the cause together.

The role of professional, low-caste actors in this process is not at all clear. But there is a body of evidence showing that military forces and experts performed plays as martial rituals in earlier eras. These martial rituals appear to be the same plays performed by professional actors.

This raises the question, were actors the priests of martial arts as religion? Also, how were these rituals different in times or war and in times of peace? Could the martial order the rituals established be conferred to serve commerce, cooperation, and well being? Could the enactment of ritual violence be experienced as an affirmation of all that was good?

In Chinese cosmology, violence is usually caused by conflicting emotions. Conflicting emotions along with desperate unfulfilled or unresolved desires can linger after a person dies. These are of course carried forward by the continuing intertwined convictions of the living. For instance, I’m quite comfortable with the idea of killing Nazi’s, I don’t need to know much else about them. Were I to kill a Nazi, we might say that my actions were caused by the lingering desire to avenge my ancestors, who have become ghosts.

In Chinese culture when someone dies naturally of old age they get a place on the family alter and are incorporated into family rituals, the purpose of which is to resolve these conflicting emotions and acknowledge and carry forward the positive model and contributions of the dead to family and society.

In the case of someone who dies an unnatural violent death, they are not included in the family alter and they become a kind of ghost that needs a place live. A shrine must be built as a site for people to both forgive and otherwise resolve old commitments and establish new ones. When large numbers of people are killed in battle, these unresolved spirits leave vast amounts of conflicting emotions spinning around for years, sometimes generations. In Chinese religious cosmology if these ghosts are not appeased, they can survive in lowly wild animals, trees, and even in grasses. As metaphor they get buried and they put down roots in the earth.

Canonization rituals were performed before battles to clarify the intentions of the combatants and infuse them with demonic powers, tamed resident demons and baleful spirits of past conflicts who have agreed in ritual to serve righteous causes. Canonization rituals after battles attempted to incorporate all the dead, especially the leaders of the losing side, into the service of the new order. In a very simple and direct way, honoring the enemy’s dead created a basis for the survivors to save face, go on with their lives and eventually forgive.

The term feng 封 (canonization) literally means to contain or enclose. It implies the container of ritually correct behavior, and the taming or pacifying (an 安, as in anjin in taijiquan) of unruly demons and baleful spirits. Is this why mothers and fathers across America are putting their kids in martial arts classes?

When people went into battle they thought of themselves being accompanied by demonic warriors, martial arts routines must have been part of the rituals for making this real. Meulenbeld explores the direct connections between Daoist thunder rituals as theatrical displays of violence and narratives of the transformation of demons into gods. Or rather he argues that is what literature was!

I suspect every traditional martial art was originally named after one of these rituals. Meulenbeld’s explorations of Guanyu, Xuanwu and Nezha as demons transformed into gods through these forms of ritual literature are astounding. I hesitate to spill the beans on all this in a review, but allow me to hint. Nezha the child-god is one among, and the leader of, the eight thunder gods, all of whom ride spinning fire wheels. What martial art aspires to child-like smooth movements, holds its hands in the mudra of thunder bolts (vajra) and travels in a circle as if moving on a spinning fire wheel? Baguazhang perhaps? Yes, you did here it here first.

Embodied martial arts as we know them today is certainly not the subject of Demonic Warfare, it is not discussed directly. But this book does explain things like the origins of the five generals that are the likely basis for Xingyiquan, and the origin of the name of my broad sword routine, Five Tigers Sword (Wuhu Dao). It does describe the context in which collections of local animal spirit powers were put into rituals, a better explanation for many martial arts than I have heard anywhere.

Demonic Warfare also presents a fair amount of textual evidence that theatrical plays were performed by combatants in earlier eras. The questions this raises are an iceberg waiting to sink three generations of defensive martial arts scholarship.

Allow me to back pedal for a moment. The biggest difference between Chinese martial arts and the rest of martial skills training world-wide is the taolu-- the long form routines which are characteristic of Chinese marital arts. These long patterns of movement have always been hard to explain, what precisely is their importance? What justifies their prevalence? The arguments have always been weak. Are forms a way to compile knowledge of all the variations? are they endurance training? or simply a minimum daily dose of discipline. Obviously there are more direct ways to training these skills or achieving these results. Why use a form? Countless 20th Century bravos have advocated tossing out the forms.

Now we have a better answer. Martial arts forms are rituals of canonization and transformation that integrate demonic warfare with the practice of real violence. This knowledge and practice was once ubiquitous! It was fully integrated into the popular forms of entertainment, it was cherished by communities as a source of commitment and inspiration.

Why should today’s martial artists care? Well first off, we can stop telling false tales, we can drop all the historic defensiveness, the incomprehensible sense of outrage, and the fear that real might be fake! But after that, with this knowledge, we are in a better position to think about the importance martial arts play in our lives, the real and available connections between martial arts enlightenment, vigor, spontaneity and expressivity.

[Note: If you buy books through the links on this post Amazon will send us a percentage!]