Mistakes

/ Elaine Scarry's book On Beauty and Being Just begins by explaining that there are two types of mistakes we make about beauty. The first is the mistake of thinking something is not beautiful and later realizing that it is. The second mistake is thinking something is beautiful and later realizing that we've been duped. She then goes on to argue that it is our experience of these two types of mistakes which gives us our sense of justice. It's a sweet argument. (I'll come back to this.)

Elaine Scarry's book On Beauty and Being Just begins by explaining that there are two types of mistakes we make about beauty. The first is the mistake of thinking something is not beautiful and later realizing that it is. The second mistake is thinking something is beautiful and later realizing that we've been duped. She then goes on to argue that it is our experience of these two types of mistakes which gives us our sense of justice. It's a sweet argument. (I'll come back to this.)What is the role of the artist? This question has been bugging me lately. Recently an experienced arts teacher, who is a director of an organization I work for, came to observe and evaluate one of my kids classes. He gave me a stellar review. Saying that I'm doing everything right, that my teaching is nuanced, that I inspire creativity, kinesthetic awareness and critical thinking, that my classes produce results, and draw on a deep knowledge of art and culture. He even wants to bring beginning teaching artists to watch me teach, as a model of great teaching. But, I learned... and this is a kicker... that I'm terrible with other adults and lack professionalism in relationships with other artists and administrators. For instance, I show my annoyance at meetings by putting my head on the table and groaning quietly to myself, I start arguments and I make shocking comments that no body understands (cognitive dissonance).

Is this what being an artist is for me? I'm not apologetic. I dropped out of high school because I didn't want to sit in chairs anymore. I get a guilty conscious if I think I've been too nice in a situation which required bluntness.

The arts organization I work for used to have a Japanese Artistic Director. She had a deep respect for artists. It now occurs to me that part of that respect may simply have been her Japanese upbringing. In Japan, artists are expected to be outrageous, unusual, spontaneous, unpredictable and moody. Japanese culture has enormous tolerance for non-conformist behavior from artists.

I hear sometimes from my left leaning friends that artists aren't rewarded enough for their art unless they "sell out." That it would be a better world if artists could easily find monetary support for making their art, even if what they do doesn't sell or isn't saleable. I wonder if the opposite is true. Does our society try to pay-off good artists so that they will be less disruptive? That is, in effect, what I'm being told, "You get paid to come to meetings, can't you just be more like everyone else?" No, I answer, it isn't worth the pay. But I worry that some day someone might pay me enough to be nicer than I want to be.

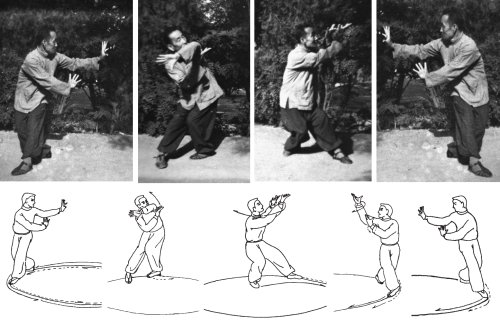

Then I start to question that list of things in the second paragraph which I'm supposedly doing right. My teaching is nuanced? Really? More like boldly physical and deeply respectful of natural aggression. I guess I do inspire creativity, "Invent a new way to break your partner's arm. You have 30 seconds. Go!" Critical thinking? I think that was an accident. How about, I expose people to the profoundly irrational nature of the heart mind connection.

Getting back to the first paragraph, what is the relationship between an artist's role in society and beauty itself? I believe it is my duty to point out mistakes about beauty. I believe that recognition of the enormous number of mistakes I've made about beauty inspires me as an artists and as a person who seeks justice. I feel a missionary duty to make beauty, whatever that may be, available and accessible. And also to protect beauty from forces which might destroy it.

It's overwhelming to contemplate all the mistakes I've made in my practice as a martial artist. I look back at the years and I see so many mistakes, things I thought were correct, things I thought would lead to greater beauty, but which later turned out to be distractions or wrong turns. It's almost as if my practice is simply the process of discovering and correcting errors about what's beautiful.

As a teacher my job is, my calling is, bringing out beauty that otherwise would go unnoticed, unclaimed, uncreated, or unfelt. In that sense, I am armed and dangerous.

The first time I met George Xu, 22 years ago, he said to me, "What's the point of punching if you don't have enough power to break bones?" At that moment I realized that there was something beautiful about breaking bones that I had been missing.

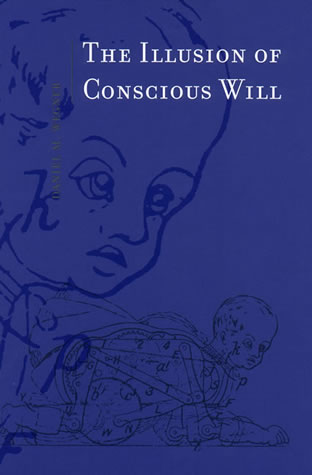

Wow, isn’t it ironic that I sometimes want to write about something but can’t find the words. It’s actually so common an experience that we hardly even notice the irony. It’s as if I have to not care too much to be able to write. I have to let go, or trick my conscious will out of the way to improvise the actual text through my fingertips. Martial arts have similar requirement; and healing does too. I suppose that letting go is the fruition of non-conceptual meditation. Is the ability to improvise is an indicator that a person is seeing things as they actually are?

Wow, isn’t it ironic that I sometimes want to write about something but can’t find the words. It’s actually so common an experience that we hardly even notice the irony. It’s as if I have to not care too much to be able to write. I have to let go, or trick my conscious will out of the way to improvise the actual text through my fingertips. Martial arts have similar requirement; and healing does too. I suppose that letting go is the fruition of non-conceptual meditation. Is the ability to improvise is an indicator that a person is seeing things as they actually are? He concludes that conscious will is an illusion, we feel like we are willing our actions because our actions usually correspond with our experience of willing them, not because our conscious will actually causes our actions. But conscious will is like a compass on a boat. It tells us where we are going, makes us feel guilty so that we change course, or proud so that we charge ahead. It manages our preferences.

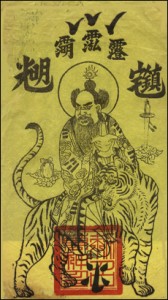

He concludes that conscious will is an illusion, we feel like we are willing our actions because our actions usually correspond with our experience of willing them, not because our conscious will actually causes our actions. But conscious will is like a compass on a boat. It tells us where we are going, makes us feel guilty so that we change course, or proud so that we charge ahead. It manages our preferences. Thus, if we want our jing, our structure body, to be free, it must follow the qi; but if the qi leads, our fighting techniques will stagnate at the developmental level of a 2 year old. So, we say, the spirits (shen) must lead the qi. What are the spirits? Perhaps they are a blend of our imagination and the kinesthetic experience of our environment, without the conscious will?

Thus, if we want our jing, our structure body, to be free, it must follow the qi; but if the qi leads, our fighting techniques will stagnate at the developmental level of a 2 year old. So, we say, the spirits (shen) must lead the qi. What are the spirits? Perhaps they are a blend of our imagination and the kinesthetic experience of our environment, without the conscious will? I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an  Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity).

Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity). Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead.

Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead. Jason Couch of Martial History Magazine sent me this article he put together

Jason Couch of Martial History Magazine sent me this article he put together  The Uncarved Block is one of the primary metaphors for the concept/anti-concept known as wuwei. The Daodejing suggests that we be like an uncarved block of wood. The implication is that once a block of wood is fashioned into something, it loses it’s potential to be something else. Once we make a decision, it cuts off certain options. In other words, it is often good to wait. But the Daodejing isn’t telling us to be indecisive. It doesn’t say, “in difficult situations--waver!” It also doesn’t say be slow, like a tree; or “be inactive,” like a log or a stump. It says be like a partially processed block of wood. Since the Daodejing doesn’t give us any idea how big this block of wood might be, or what it might be for, we can speculate. Our block of wood could be carved into any sort of deity or icon, or perhaps a boat, a cabinet, a ladle, or a coffin. The Daodejing is using this metaphor to point to a process which takes place when we make something. It is not saying, “Don’t make stuff.” Sometimes a decision can position us for more possibilities, sometimes a decision can limit us. Is this better than that? Be comfortable with ambiguity, but have a few uncarved blocks hanging around in case you need them.

The Uncarved Block is one of the primary metaphors for the concept/anti-concept known as wuwei. The Daodejing suggests that we be like an uncarved block of wood. The implication is that once a block of wood is fashioned into something, it loses it’s potential to be something else. Once we make a decision, it cuts off certain options. In other words, it is often good to wait. But the Daodejing isn’t telling us to be indecisive. It doesn’t say, “in difficult situations--waver!” It also doesn’t say be slow, like a tree; or “be inactive,” like a log or a stump. It says be like a partially processed block of wood. Since the Daodejing doesn’t give us any idea how big this block of wood might be, or what it might be for, we can speculate. Our block of wood could be carved into any sort of deity or icon, or perhaps a boat, a cabinet, a ladle, or a coffin. The Daodejing is using this metaphor to point to a process which takes place when we make something. It is not saying, “Don’t make stuff.” Sometimes a decision can position us for more possibilities, sometimes a decision can limit us. Is this better than that? Be comfortable with ambiguity, but have a few uncarved blocks hanging around in case you need them.

The moment I start writing a blog post, or you start reading one, the danger that we will lose sight of wuwei increases. Because reading and writing is a form of carving. The moment we put pen to paper we risk crossing over into the land of methods.

The moment I start writing a blog post, or you start reading one, the danger that we will lose sight of wuwei increases. Because reading and writing is a form of carving. The moment we put pen to paper we risk crossing over into the land of methods. gfu on the brain.” It’s a possibility, I admit. Sometimes I get excited and I start to see martial arts in everything (Richard Rorty would call it the narcissistic tendency of powerful ideas). I can use Kungfu power to scrub the dishes. I can use maximum muscle tendon twisting to wring-out the laundry. I can set the table “the way a beautiful woman would do it,” (that’s an alternate name for Baguazhang seventh palm change).

gfu on the brain.” It’s a possibility, I admit. Sometimes I get excited and I start to see martial arts in everything (Richard Rorty would call it the narcissistic tendency of powerful ideas). I can use Kungfu power to scrub the dishes. I can use maximum muscle tendon twisting to wring-out the laundry. I can set the table “the way a beautiful woman would do it,” (that’s an alternate name for Baguazhang seventh palm change). I’ve had a taste of several different styles of African and African Diaspora Dances but my actual training was in Congolese and African-Haitian Dance. My Congolese Dance teacher, Malonga Casquelourd, learned to dance from soldiers on army bases.

I’ve had a taste of several different styles of African and African Diaspora Dances but my actual training was in Congolese and African-Haitian Dance. My Congolese Dance teacher, Malonga Casquelourd, learned to dance from soldiers on army bases.

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background.

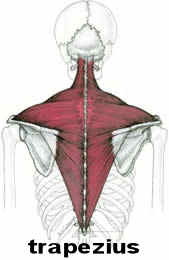

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background. Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.)

Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.) The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.

The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.