The Illusion of Conscious Will

/ Wow, isn’t it ironic that I sometimes want to write about something but can’t find the words. It’s actually so common an experience that we hardly even notice the irony. It’s as if I have to not care too much to be able to write. I have to let go, or trick my conscious will out of the way to improvise the actual text through my fingertips. Martial arts have similar requirement; and healing does too. I suppose that letting go is the fruition of non-conceptual meditation. Is the ability to improvise is an indicator that a person is seeing things as they actually are?

Wow, isn’t it ironic that I sometimes want to write about something but can’t find the words. It’s actually so common an experience that we hardly even notice the irony. It’s as if I have to not care too much to be able to write. I have to let go, or trick my conscious will out of the way to improvise the actual text through my fingertips. Martial arts have similar requirement; and healing does too. I suppose that letting go is the fruition of non-conceptual meditation. Is the ability to improvise is an indicator that a person is seeing things as they actually are?I generally don’t like psychology much. Perhaps it is because I have a tiny lingering unconscious desire to do damage to the psychiatrist I saw from age 4 to 7. In my 20’s I went back and found that very psychiatrist. My mother, my father and the psychiatrist all have different explanations for why it was desirable to sequester me twice a week in a room with a desk and venetian blinds. Not only was communication lacking in the process, but no one could agree on what the intention was. It makes me wonder whether agreement is actually a significant factor in cases of consensus activity, even in situations where people say they agree.

How do we know what we know? What causes unconscious behavior? How do we attribute agency? Asian arts present us with a challenge in that they are rooted in a cosmology which presumes that all agents are mutually self-re-creating. Is the art making me? or am I making the art?

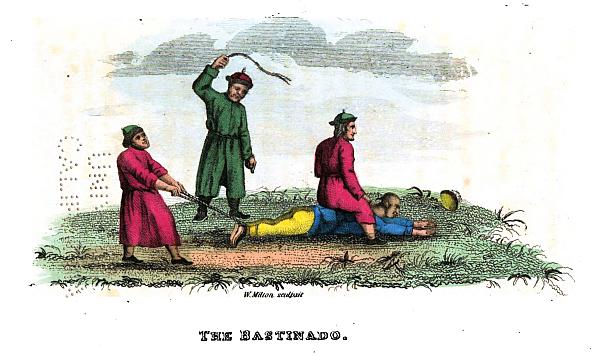

So with all that in mind I recently read The Illusion of the Conscious Will, by Daniel M. Wegner, which is an exploration of how conscious will effects our actions. It is a very wide ranging survey of mostly psychological studies and experiments dating back to the 1800's, with some anthropology and neurology studies as well. With an eye to exposing the mechanism of conscious will and how it interacts with spontaneous action and unconscious action; the book explores multiple personalities, hypnosis, trance possession, and many other more mundane ways in which we doubt whether a persons actions are consciously willed.

Chew on this:

Perhaps the experience of involuntariness helps to shut down a mental process that normally gets in the way of control. And, oddly, this mental process may be the actual exercise of will. It may be that the feeling of involuntariness reduces the degree to which thoughts and plans about behavior come to mind. If behavior is experienced as involuntary, there may be a reduced level of attention directed toward discerning the next thing to do or for that matter, towards rehearsing the idea of what one is currently doing. A lack of experienced will might thus influence the force of will in this way, reducing the degree to which attention is directed to the thoughts normally preparatory to action. And this could be good.

The ironic process of mental control (Wegner 1994) suggests that there are times when it might be good to stop planning and striving. It is often possible to try too hard....

He concludes that conscious will is an illusion, we feel like we are willing our actions because our actions usually correspond with our experience of willing them, not because our conscious will actually causes our actions. But conscious will is like a compass on a boat. It tells us where we are going, makes us feel guilty so that we change course, or proud so that we charge ahead. It manages our preferences.

He concludes that conscious will is an illusion, we feel like we are willing our actions because our actions usually correspond with our experience of willing them, not because our conscious will actually causes our actions. But conscious will is like a compass on a boat. It tells us where we are going, makes us feel guilty so that we change course, or proud so that we charge ahead. It manages our preferences.Re-reading what I just wrote, I imagine it is hard to follow. This particular conundrum resists language; if you are not in control, how can you change coarse? The book is great because it doesn't rely on philosophical or psychological language, instead, it describes experiments one after another. For instance, when a person wills themselves to not do something, they make themselves statistically more likely to do the thing. Despite my intentions, I always use to throw the Frisbee at my elderly neighbor's window just at the moment when she was looking.

We are not our minds. We don’t actually know what we are. If we use our conscious mind in a fight we will probably lock up or freeze. But that remains an interesting debate. When faced with an opponent who we believe intends to do us harm, what happens to our will? It seems that intent also has a great potential to get in the way of our ability to respond. We talk about intent in internal martial arts a lot. I argue, following Wang Xiangzhai, that if an opponent's intent comes to a point or to a line or a curve, he will be easy to control. Only if my intent is spherical can I really hope to reliably defeat a larger opponent who is trying to hurt me.

No shortage of irony here.

From reviewing the scientific experiments in this book, I find evidence of an active awareness underneath our conscious will. Freud pointed to the Id, a primal self. In Daoist cosmology we refer to a qi body which can act very freely and spontaneously. In observing that this qi body coincides with a person, we could brake all protocol and just call it Laozi, an old baby, (lao=old, zi=baby). This Laozi doesn’t have it’s own stop button. Without the conscious will to inhibit it, it would do silly things like walk off of cliffs or try to squeeze through keyholes. The qi body is both the source and the ingredient of inspiration, but it is not at all articulate. It doesn’t have preferences or opinions or hidden agendas because it has no memory. All memory belongs to the realm of jing, not qi. All inhibition comes from trying to use the mind to control the composite body-structure-memory.

Thus, if we want our jing, our structure body, to be free, it must follow the qi; but if the qi leads, our fighting techniques will stagnate at the developmental level of a 2 year old. So, we say, the spirits (shen) must lead the qi. What are the spirits? Perhaps they are a blend of our imagination and the kinesthetic experience of our environment, without the conscious will?

Thus, if we want our jing, our structure body, to be free, it must follow the qi; but if the qi leads, our fighting techniques will stagnate at the developmental level of a 2 year old. So, we say, the spirits (shen) must lead the qi. What are the spirits? Perhaps they are a blend of our imagination and the kinesthetic experience of our environment, without the conscious will?This is a great book. It isn’t easy to read, but hardly anything I recommend is. Terry Kleeman recommended this book when I met with him at the food court under Ikea in Taipei. I was presenting my theory of Baguazhang’s original connections to Daoist ritual, describing how bagua can be organized around different trance states. He was very friendly and skeptical, pointing out as so many others have, that perceiving Taiwanese rituals in terms of trance is a Western intellectual construction. On the other hand he said that his Daoist priest informants consider their martial arts prowess to contribute to their ritual efficacy and potency.

But back to the book. It is a really good Eastern-Western bridge to understanding why Internal Martial artists talk about experiencing shen (spirit) outside of the body. It also threw me into a spiral of self-doubt. I started asking a lot of, “Am I fooling myself?” type questions. Am I hypnotizing myself? Am I hypnotizing my students?” For this reason alone I would recommend it. I decided that the possibility that I am fooling myself or my students is high. Not all the time, but certainly sometimes. And that’s not always bad either, but ignoring it is a recipe for disaster. I’ve started catching myself in the act of self-hypnosis.

For instance, I was teaching push-hands the other day and I stopped myself from striking a student who was making the mistake of forcing my hand into his head. This is a flaw in my teaching even if I stop and explain it to the student because the student probably won’t learn from his mistake unless he gets hit. But even worse, it’s a bad habit because I’m training myself to not hit in certain situations. So whether in the dojo or the cafe, beware of nice people! Only princes, psychiatrists and con-artists are charming! The next time he made that mistake I clocked him.

Now that I’ve done all this writing, by tricking my conscious will out of the way, I’m going to re-establish control, good-bye.

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an

I have written elsewhere about martial arts forms being an  Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity).

Confucianism is founded on the idea that we inherit a great deal from our ancestors, including body, culture, and circumstance. We also, to some extent, inherit our will, our intentions, and our goals. The Confucian project is predicated on the idea that we have a duty to carryout and comprehend our ancestors' intentions in a way which is coherent with our own circumstance and experiences. In practice, it is entirely possible that we have two ancestors who died with conflicting goals, or an ancestor who died with an unfulfilled desire, like unrequited love, or an ancestor who wished and plotted to kill us. Our dead ancestors have become spirits whose intentions linger on in us to some extent in our habits and our reactions to stress. It is the central purpose of Confucianism to resolve these conflicts and lingering feelings of distress through a continuous process of self-reflection and upright conduct--so that we may leave a better world for our descendants. The metaphor is fundamentally one of exorcism. We empty ourselves of our own agenda so that we might consider the true will of our ancestors (inviting the spirits), then we take that understanding and transform it into action (dispersion and resolution). Finally we leave our descendants with open ended possibilities, support, and clarity of purpose (harmony, rectification, unity). Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead.

Daoist Meditation takes emptiness as it’s root. All Daoist practices arise from this root of emptiness. The main distinction between an orthodox Daoist exorcism and a less than orthodox exorcism is in fact the ability of the priests to remain empty while invoking and enlisting various potent unseen forces (gods/demons/spirits/ancestors) to preform the ritual on behalf of a living constituency, or the recently dead. Jason Couch of Martial History Magazine sent me this article he put together

Jason Couch of Martial History Magazine sent me this article he put together  The Uncarved Block is one of the primary metaphors for the concept/anti-concept known as wuwei. The Daodejing suggests that we be like an uncarved block of wood. The implication is that once a block of wood is fashioned into something, it loses it’s potential to be something else. Once we make a decision, it cuts off certain options. In other words, it is often good to wait. But the Daodejing isn’t telling us to be indecisive. It doesn’t say, “in difficult situations--waver!” It also doesn’t say be slow, like a tree; or “be inactive,” like a log or a stump. It says be like a partially processed block of wood. Since the Daodejing doesn’t give us any idea how big this block of wood might be, or what it might be for, we can speculate. Our block of wood could be carved into any sort of deity or icon, or perhaps a boat, a cabinet, a ladle, or a coffin. The Daodejing is using this metaphor to point to a process which takes place when we make something. It is not saying, “Don’t make stuff.” Sometimes a decision can position us for more possibilities, sometimes a decision can limit us. Is this better than that? Be comfortable with ambiguity, but have a few uncarved blocks hanging around in case you need them.

The Uncarved Block is one of the primary metaphors for the concept/anti-concept known as wuwei. The Daodejing suggests that we be like an uncarved block of wood. The implication is that once a block of wood is fashioned into something, it loses it’s potential to be something else. Once we make a decision, it cuts off certain options. In other words, it is often good to wait. But the Daodejing isn’t telling us to be indecisive. It doesn’t say, “in difficult situations--waver!” It also doesn’t say be slow, like a tree; or “be inactive,” like a log or a stump. It says be like a partially processed block of wood. Since the Daodejing doesn’t give us any idea how big this block of wood might be, or what it might be for, we can speculate. Our block of wood could be carved into any sort of deity or icon, or perhaps a boat, a cabinet, a ladle, or a coffin. The Daodejing is using this metaphor to point to a process which takes place when we make something. It is not saying, “Don’t make stuff.” Sometimes a decision can position us for more possibilities, sometimes a decision can limit us. Is this better than that? Be comfortable with ambiguity, but have a few uncarved blocks hanging around in case you need them.

The moment I start writing a blog post, or you start reading one, the danger that we will lose sight of wuwei increases. Because reading and writing is a form of carving. The moment we put pen to paper we risk crossing over into the land of methods.

The moment I start writing a blog post, or you start reading one, the danger that we will lose sight of wuwei increases. Because reading and writing is a form of carving. The moment we put pen to paper we risk crossing over into the land of methods. gfu on the brain.” It’s a possibility, I admit. Sometimes I get excited and I start to see martial arts in everything (Richard Rorty would call it the narcissistic tendency of powerful ideas). I can use Kungfu power to scrub the dishes. I can use maximum muscle tendon twisting to wring-out the laundry. I can set the table “the way a beautiful woman would do it,” (that’s an alternate name for Baguazhang seventh palm change).

gfu on the brain.” It’s a possibility, I admit. Sometimes I get excited and I start to see martial arts in everything (Richard Rorty would call it the narcissistic tendency of powerful ideas). I can use Kungfu power to scrub the dishes. I can use maximum muscle tendon twisting to wring-out the laundry. I can set the table “the way a beautiful woman would do it,” (that’s an alternate name for Baguazhang seventh palm change). I’ve had a taste of several different styles of African and African Diaspora Dances but my actual training was in Congolese and African-Haitian Dance. My Congolese Dance teacher, Malonga Casquelourd, learned to dance from soldiers on army bases.

I’ve had a taste of several different styles of African and African Diaspora Dances but my actual training was in Congolese and African-Haitian Dance. My Congolese Dance teacher, Malonga Casquelourd, learned to dance from soldiers on army bases.

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background.

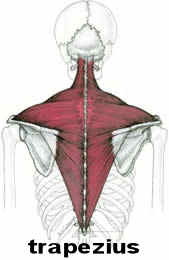

As someone whose job it is to translate ideas from one culture to another, the pressure to use more familiar language is always floating around in the background. Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.)

Basic structure training in Internal Martial Arts gets us to stop using these three big muscles for stabilization by getting us to put our weight directly on our bones. The other 400 or so smaller muscles in our bodies are then used to focus force along our bones through twisting, spiraling and wrapping. In that sense, the early years of internal martial arts training teaches us to use our muscles like ligaments; or put another way, the primary function of the smaller muscles becomes ligament support. (To develop this capacity in ones legs requires many years of training.) The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.

The three big muscles are already so big they don’t need to be strengthened but they do need to be enlivened. All three muscles should be like tiger skin or octopi, able to expand and condense and move in any direction. They then can take over control of the four limbs in such a way that movement becomes effortless--even against a strongly resistant partner. If you accomplish this all of your smaller muscles will be doing the task of transferring force to the three big muscles---preventing an opponent from being able to effect your body through your limbs. Yet whenever your limbs make contact with your opponent, he will be vulnerable to the force of your three big muscles.

A while back I wrote a post called,

A while back I wrote a post called,  Here is an article from the NYT about

Here is an article from the NYT about