Ghosts and Demons!

/ As I said yesterday, perhaps our most defining characteristic as human beings is our ability to make commitments. But such an observation brings with it the reality that we can make commitments to things which are not real, or not true. At one extreme we can make vague wishy-washy commitments, and at the other extreme we can swear an oath in blood to repeat and maintain a lie.

As I said yesterday, perhaps our most defining characteristic as human beings is our ability to make commitments. But such an observation brings with it the reality that we can make commitments to things which are not real, or not true. At one extreme we can make vague wishy-washy commitments, and at the other extreme we can swear an oath in blood to repeat and maintain a lie.Enter Yin Spirits.

A clear strong commitment can't be made when a previous commitment is in conflict with it. If the previous and now conflicting commitment is vague, irrational, or desperate, Daoists would call it a ghostly commitment. Lingering ghostly commitments tend to dilute new commitments and thus create more ghostly commitments over time.

Where do weak commitments come from in the first place? What is a ghost or a demon? To answer those two questions I'm going to have to ask another question first.

What happens when we die? From a Daoist point of view there are five possibilities; we become a god, a ghost, a demon, an immortal, or a supportive ancestor.

At the moment of death everything which is subtle and light rises upward to join with heaven; and everything gross, heavy and thick sinks downward and becomes one with earth. The only problem is that this de-polarization can take a while to complete. The stuff that makes us what we are does not disperse immediately.

At the moment of death everything which is subtle and light rises upward to join with heaven; and everything gross, heavy and thick sinks downward and becomes one with earth. The only problem is that this de-polarization can take a while to complete. The stuff that makes us what we are does not disperse immediately.Usually when a person dies they still have a few things they wish to do, they still have a desire that is unfulfilled, or a fear that lingers. Most of these wishes quickly fade as the person dies, but not all.

A desire like, "I want to sit in my favorite chair and look out the window," would likely fade fast after death. But we've all heard the story of the unfulfilled woman who sat waiting at the window for a lover to come, only to hear a false report that something terrible has befallen her man. The woman commits suicide just at the moment her lover returns! What is left is the type of feeling that can hang around for a while after death. We don't know why this happens, but we do know that the intense feeling and lingering commitments tend to be carried forward through those who were emotionally close to the person who died.

A vow like, "I want my sons and daughters to avenge my murder," has a good chance of continuing on in some form through the living. This is true even if the sons and daughters realize that vengeance is a mistake and choose not to seek it. The fact that a parent died with such a potent unresolved will has a real effect on the children. It has the potential to interfere with their ability's to make strong clear commitments.

A behavior like a craving for a cigarette usually fades shortly after death, but in some circumstances it will be carried forward by ones descendants. This is especially true for those quirky behaviors we inherit from our families which have vague or unknown origins.

When parents experience extreme trauma it is not unusual for them to keep the details of that trauma hidden from their children but to pass on quirky or frightened behavior with out explanation. For example, the child of a Holocaust surviver who acts overly cautious about food, as if he were afraid of being poisoned, but he isn't actually afraid of that.

The Daoist definition of a ghost is a weak nagging commitment. A commitment which doesn't have enough qi to complete itself. Gods and Demons are not so different from each other. A god lower down in the Heavenly Hierarchy tends to get his start as a human who decides to keep his commitment even though he knows it will kill him.

Demon births tend to start with humans who have made very strong commitments to fantasies which spread terror and lies. After such a person dies, people who have inherited weak commitments sometimes make offerings to such a person. They collect amulets and symbols of the dead man's life and thus magnify the will of the dead over time. Hitler is a good example of a demon who lingers on through the weak commitments of the living.

It matters not at all whether you or I believe in ghosts or demons, they are real!

A Way of Life

A Way of Life Becoming an Immortal

Becoming an Immortal I want to announce that we have officially entered the Era of Conditioning.

I want to announce that we have officially entered the Era of Conditioning. I'm anti-conditioning. I believe in doing things form the inside out. If I said, "I believe in beginning from the heart," you could accuse me of being a silly romantic. But it's not because I want to bring out genius, or preserve mystery, I just prefer spontaneous unconditioned responses.

I'm anti-conditioning. I believe in doing things form the inside out. If I said, "I believe in beginning from the heart," you could accuse me of being a silly romantic. But it's not because I want to bring out genius, or preserve mystery, I just prefer spontaneous unconditioned responses.

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism.

way I do, than you also understand that it is not referring to a remedy. It is an engaged process of complete embodiment. My regular readers will recognize this statement as being in tune with a world view that encouraged long-life, slow motion, continuous and consensual exorcism.

their students or clients that I don't get. If you tap into a client's insecurities, or their desire for power, by convincing them that they will be freer, or happier, or stronger, or more preceptive, or even more intuitive, if only they quit eating fried chicken and do some groovy breathing exercise--who am I to get in the way? Those commitments are legitimately good for one's health. Other people are free to subordinate themselves to people and ideas.

their students or clients that I don't get. If you tap into a client's insecurities, or their desire for power, by convincing them that they will be freer, or happier, or stronger, or more preceptive, or even more intuitive, if only they quit eating fried chicken and do some groovy breathing exercise--who am I to get in the way? Those commitments are legitimately good for one's health. Other people are free to subordinate themselves to people and ideas. As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism.

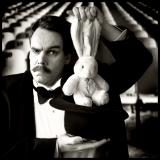

As Americans we have always come face to face with cultures different from our own. Multi-culturalism is an ethic based on our sense of what is right and good and desirable in a society. Unfortunately multiculturalism often gets conflated with cultural relativism. If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow.

If you are teaching "qigong healing" and just happen to pull a rabbit out of your hat, is it ethical to say "My qi is feeling jumpy today?" I think not. I think you should say, "I will now attempt to pull a rabbit out of my hat," do the deed, then say, "Ta-Dah!" and take a bow. Chinese popular religion is pretty dynamic. This

Chinese popular religion is pretty dynamic. This  Daoist priests are also called Tianshi (Celestial Masters) because they are responsible for determining, managing and updating the hierarchy of gods. The Rabbit god falls under the control of the City God. The shrine to the City God was likely the focal point of martial arts training during the Song Dynasty, and is the context from which the word gongfu (Kungfu) got its meaning. Gongfu means "meritorious action," people training martial arts on behalf of the community did so as part of their participation in the cult of the City God.

Daoist priests are also called Tianshi (Celestial Masters) because they are responsible for determining, managing and updating the hierarchy of gods. The Rabbit god falls under the control of the City God. The shrine to the City God was likely the focal point of martial arts training during the Song Dynasty, and is the context from which the word gongfu (Kungfu) got its meaning. Gongfu means "meritorious action," people training martial arts on behalf of the community did so as part of their participation in the cult of the City God. In an earlier post I talked about the invocation of

In an earlier post I talked about the invocation of  teaching, except to say, "sit still."

teaching, except to say, "sit still."

If it is true that, at the time the various taijiquan postures got their names the main people practicing taijiquan were

If it is true that, at the time the various taijiquan postures got their names the main people practicing taijiquan were