In general I teach that

yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong.

Generally speaking the correct posture will automatically have the right breathing and the right breathing will get you to the correct posture. In practice, however, the way we breathe tends to hold us in certain postures. Breathing is a natural anesthetic, which covers up all types of pain. When we use our breathing to try and force circulation to a certain area, the area tends to become numb. Over years, we accumulate these numb spots and our posture becomes more rigid, our breathing more restricted.

I generally teach people to stand, and to move, before teaching them breathing; however, the two are really inseparable.

Body Image

Cultural conceptions about how to breath and how to stand (posture) are so tied up in emotions, passions, fantasies and identities that either approach can take a bit of

unraveling. My experience is that if I say to someone "take a deep breath," they lift up the front of their ribcage (actually constricting their lungs which are mostly in the back) and they tend to harden their

diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

Instead I say, "Take shallow breaths in and out from your nose all the way down to your belly(dantian) and slowly/gently allow the breath(qi) to fill up your lower back/kidney area(mingmen)"

Your breathing should be like the silk spinner and the jade carver. The silk spinner uses a gentle continuous pull, no sudden jerks, and a smooth even turnaround.

The jade carver doesn't leave any scratches; the breath is inaudible, silent, with no rasping.

The great jade carver discovers what is in the jade as he is carving it, the mediocre jade carver plans out what they are going to carve in advance.Breathing is essentially about taking the nutritive qi of heaven into all the channels of the body. Our posture is formed in our

qi environment, home, school, work, car etc.... How we breath is formed inside our posture. Trying to force a particular type of breathing which doesn't match the physical structure and posture of our bodies will simply be a strain. Frustration itself is a kind of breathing.

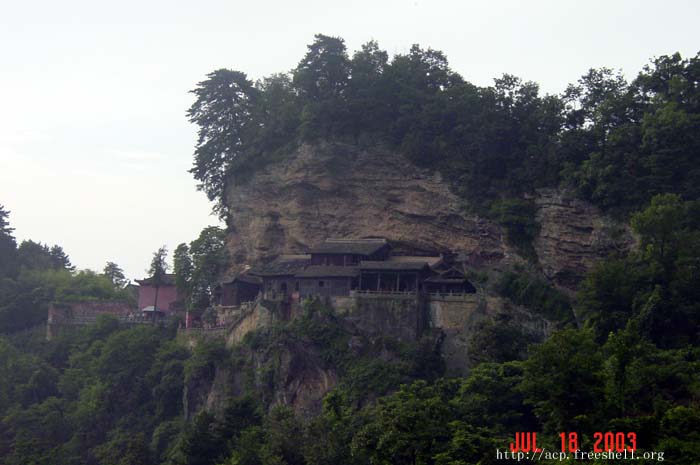

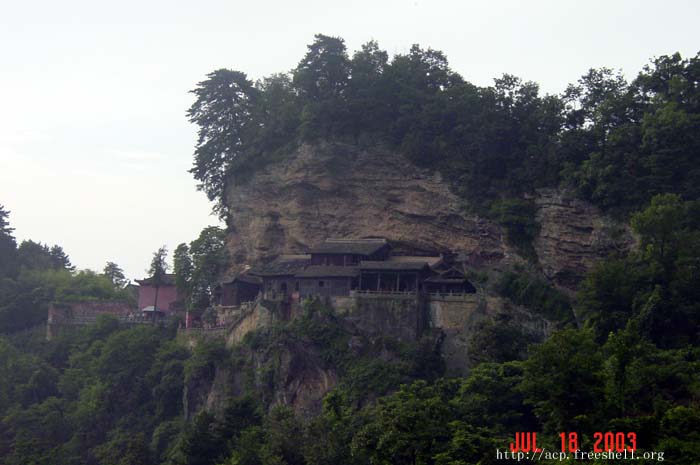

The way to change breathing is to change physical structure and posture. The way to change posture is to change the environments we live in and move through, this is the subject of fengshui. The aspect of fengshui that relates directly to qigong is the question of what environment will be most supportive of our practice. Through practicing qigong in a supportive qi environment, we develop sensitivity to the effects the

larger bodies we are living in have on our constitution, and on our breathing.

Qigong should not be used as a way to overcome a negative environment.

One of the biggest challenges of being a teacher is that students are always trying to get me to equivocate. For instance, I say, "Practice standing completely still for one hour early in the morning, everyday, before you eat breakfast."

One of the biggest challenges of being a teacher is that students are always trying to get me to equivocate. For instance, I say, "Practice standing completely still for one hour early in the morning, everyday, before you eat breakfast." In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong.

In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong. diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

Chinese Martial arts and Qigong from a Daoist point of view are non-transcendent traditions.

Chinese Martial arts and Qigong from a Daoist point of view are non-transcendent traditions.

I took the following quote from Joanna Zorya at

I took the following quote from Joanna Zorya at  It is a standard of Chinese martial arts that one should cultivate balance. When I learned my first broad sword form (wuhudao) my teacher, Bing Gong, had me learn it with the sword in the left hand because I am left handed. This meant that I had to learn a mirror image of the form he did. Being the precocious kid that I was, I taught myself the right hand too.Later a second teacher, George Xu, taught me another sword form (baxianjian). At the beginning I suggested that perhaps I should learn it left handed. His response was memorable, and classic gongfu-teacher-speak, "You don't have any idea how to use either hand...yet." (I learned it right handed.)

It is a standard of Chinese martial arts that one should cultivate balance. When I learned my first broad sword form (wuhudao) my teacher, Bing Gong, had me learn it with the sword in the left hand because I am left handed. This meant that I had to learn a mirror image of the form he did. Being the precocious kid that I was, I taught myself the right hand too.Later a second teacher, George Xu, taught me another sword form (baxianjian). At the beginning I suggested that perhaps I should learn it left handed. His response was memorable, and classic gongfu-teacher-speak, "You don't have any idea how to use either hand...yet." (I learned it right handed.)

Elisabeth Hsu wrote an article in

Elisabeth Hsu wrote an article in