Warriors Part 3

/ This is a continuation of my discussion of Warriors, part 1, and part 2.

This is a continuation of my discussion of Warriors, part 1, and part 2.

Shaman Warriors of old were experts in using Spirit(s) to invoke absolute terror in their opponents, and blind fury in their allies. In the transition from shaman warriors to lineages that follow warrior codes, some shamanism became institutionalized.

During the Holy Crusades, both sides made extensive use of protective talisman. In Indonesia, the dagger known as a Kris is understood to capture and enslave the spirits of all the people it has slain. The more dead warriors in your Kris, the more power it has. A very powerful Kris itself becomes a player, and can possess a weak owner.

This is one of the parallel stories told in the block buster hit “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.� In the beginning when Chow Yun Fat returns from his meditation retreat, Michelle Yao asks, “Why did you come back?� she is thinking, “He must have come back because he loves me.� But he doesn’t answer, he just looks over at the sword; the sword has it’s own name, Green Destiny (yuming).

In Japan, only Samurai were aloud to own swords. Swords were passed down from one generation to the next. The long sword captured the spirits of one’s opponents; the short sword captured only the spirits of ancestors who had used it to kill themselves. If a Samurai pulled out his short sword in the midst of battle, everyone would just run past him because they knew he was going to use it only on himself.

In this warrior  code, a Samurai needed only two things, fearlessness and a willingness to die. The change from Warrior to skilled technician and martial artist is marked historically with the life of Miyamoto Musashi

code, a Samurai needed only two things, fearlessness and a willingness to die. The change from Warrior to skilled technician and martial artist is marked historically with the life of Miyamoto Musashi.

Cool footnote: In the Chinese army during the Tang Dynasty there were Korean Suicide Troops, which were used in the wars against Tibet.

after the parts I think are the strongest, the points that are most central, and are the most likely to change one of our opinions.

after the parts I think are the strongest, the points that are most central, and are the most likely to change one of our opinions. Most people, including me, first learned internal martial arts and qigong with out a Daoist inspired view.

Most people, including me, first learned internal martial arts and qigong with out a Daoist inspired view. traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject keeping in mind its traditional context?

traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject keeping in mind its traditional context? A TRADITIONAL CHINESE ORIENTATION TOWARD KNOWLEDGE.

A TRADITIONAL CHINESE ORIENTATION TOWARD KNOWLEDGE. What is the appropriate attitude with which to approach a traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject of the Internal Arts keeping in mind their traditional context?

What is the appropriate attitude with which to approach a traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject of the Internal Arts keeping in mind their traditional context? I'm calling it concentrated efficiency because that is what it seems like from the outside looking in, but to actually embody either a classic text or a internal arts form feels plain, bland and simple. A traditional Chinese scholar can seamlessly weave a classic, they have memorized, in and out of their speech in such a way that someone who is unfamiliar with the classic won't notice. In fact, scholars who have memorized and embodied many classic texts can play games together where they seamlessly string together classic quotes and yet speak to each other from the heart about things which are important to them. In fact, China has a tradition of scholars with huge appetites for study who can actually quote continuously with genuineness and sincerity. To truly embody an internal practice is the same. On the outside one appears to be doing regular everyday movement, but inside the form (or we could say qigong) is happening all the time, it becomes second nature.

I'm calling it concentrated efficiency because that is what it seems like from the outside looking in, but to actually embody either a classic text or a internal arts form feels plain, bland and simple. A traditional Chinese scholar can seamlessly weave a classic, they have memorized, in and out of their speech in such a way that someone who is unfamiliar with the classic won't notice. In fact, scholars who have memorized and embodied many classic texts can play games together where they seamlessly string together classic quotes and yet speak to each other from the heart about things which are important to them. In fact, China has a tradition of scholars with huge appetites for study who can actually quote continuously with genuineness and sincerity. To truly embody an internal practice is the same. On the outside one appears to be doing regular everyday movement, but inside the form (or we could say qigong) is happening all the time, it becomes second nature. I interviewed George Xu the other day. I expect to have a video of him talking uploaded soon. He said he has video of him demonstrating in Germany that will likely go on the web by October.

I interviewed George Xu the other day. I expect to have a video of him talking uploaded soon. He said he has video of him demonstrating in Germany that will likely go on the web by October. When two different cultures meet, dance is the first art across the border. Music is very close behind. Interaction with another culture has great potential to create change; most societies fear change. This is why societies so often ban or at least try to control dance.

When two different cultures meet, dance is the first art across the border. Music is very close behind. Interaction with another culture has great potential to create change; most societies fear change. This is why societies so often ban or at least try to control dance.

When training in traditional Chinese arts, finding the time to practice consistently, actually setting time aside everyday, is most peoples biggest obstacle. The second biggest obstacle is trying to find a safe comfortable place to practice undisturbed.

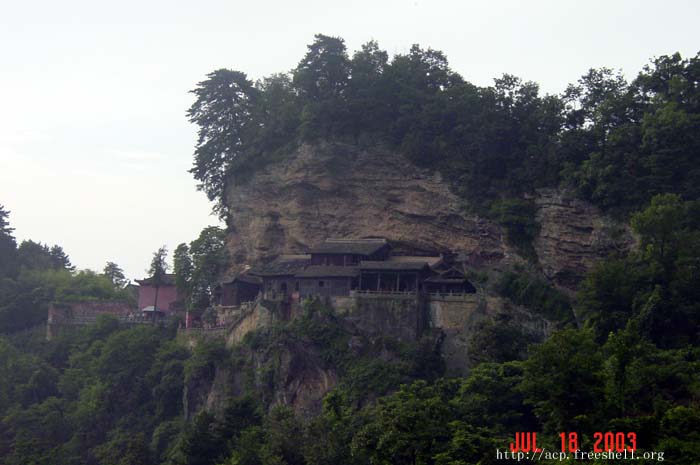

When training in traditional Chinese arts, finding the time to practice consistently, actually setting time aside everyday, is most peoples biggest obstacle. The second biggest obstacle is trying to find a safe comfortable place to practice undisturbed. The basic idea of fengshui is that the site itself is the most important consideration. Since you will be taking qi(inspiration) from the environment, the best location is a place you want to be, and that you can come to consistently. A place where you feel safe comfortable and can be alone. It should be a place where the air is fresh(free to circulate) yet still (absence of wind).

The basic idea of fengshui is that the site itself is the most important consideration. Since you will be taking qi(inspiration) from the environment, the best location is a place you want to be, and that you can come to consistently. A place where you feel safe comfortable and can be alone. It should be a place where the air is fresh(free to circulate) yet still (absence of wind).

In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong.

In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong. diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.