.jpg)

The key Taijiquan term

peng has generally been translated 'ward-off.' I think that was a good start, after all, in Chinese it is only one word, but it has a really specific meaning so I'm going to try to render it into English.

But before I do that let me say something about the various ways peng is taught. Often a teacher will push on a student and say, 'buhao'--no good-- until the student by luck or accident, responds in almost the right way. Then the teacher says 'hao.' (Or perhaps they yawn and look up at the sky as if to say, "What have the heavens brought me?") Then the teacher has you push on them and you try to

feel how they respond to your push. (Actually the word is not

feel in Chinese, it is

tingjin, which means: try to sense the inner processes you feel and translate those feelings into your own body, as if you are listening to a piece of music and wish to grasp the sentiment behind it

.)Peng is primarily taught, not by words, but by feeling, it is transmitted through touch from generation to generation. In taijiquan lingo--it is a

qi transmission.

If you have older siblings, who were in the habit of poking you in the stomach, you probably already have some 'peng' skills.

When an older sibling pokes you, several responses become available: 1. Run to mommy. 2. Try to hurt them back. 3. With a smile, and with speed, nudge their hand away from your centerline before it hurts you, being careful not to provoke them further. Obviously number 1 is ineffective in the long run. Number 2 means getting beat up. So we get good at number 3.

Peng is an aggressive act, but it is a mild aggressive act. We could say it is a small beginning that hopes not to grow into a full possession.

When we are possessed by desire, we see only the desired manifest.

DaodejingTo correctly practice

peng, is also, fundamentally, to admit that we do not have control over the future.

Here goes:

Stand upright, slightly bend your knees, relax all of your joints and lengthen the top of

your head upwards and your tail bone downwards. Relax your abdominal muscles so that your breathing no longer moves your ribs, but instead moves your lower-back region (mingmen).

Simultaniously do all of the following:

1. Gently begin

closing all of your joints, drawing your limbs inward towards the center of your body, like an amoeba shrinking. The distance between each of your bones should shrink as the sinovial fluid sack in each joint changes shape.

2. Gently wist all the tissue on your limbs in an outward direction, moving the bones as little as possible so as not to change the alignment of the knees or elbows.

3. Gently wrap the tissue of your torso, internal organs, and generally anything you can feel, in an outward direction. Be particularly carefully not to arch your spine or collapse your chest.

4. Using the least possible effort move your writs (upward and forward) at a perfect 45 degree angle.

5. Shift your weight very slightly forwards from the center of your feet, so that if someone were pushing you from the front while you are shrinking, you would move almost imperceptibly underneath them.

OK that's the underlying structure: the jing component. Here are the qi and shen components.

Update 7/29/071. If your alignment is correct you will feel something rising from the ball of the foot, bubbling well point, which travels up your legs, then up your back, through your arms and then out the wrists.

2. Fill your whole body with the feeling of steam, so that circulation to every part of your body is robust.

3. Feel clouds circling around the surface of your body in the direction of the twisting and wrapping.

4. Draw up a thick heavy black goop from the earth. (This one is not universal, there are versions of it that use water or sand. Others connect to heavenly bodies, or spontaneously plan routes out into the distance. This is known as the jingshen component and can be invented.)

5. Sense outward in all directions.

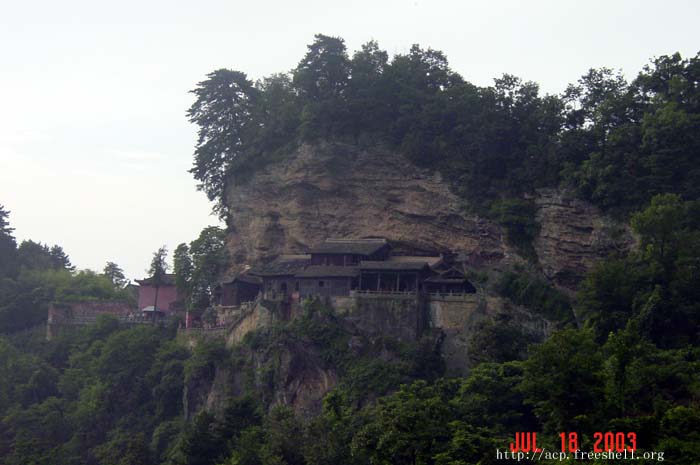

Is this what you do?By the way the picture is of Chen Manching doing one handed peng, so it is a little different than the description, but internally the same.

after the parts I think are the strongest, the points that are most central, and are the most likely to change one of our opinions.

after the parts I think are the strongest, the points that are most central, and are the most likely to change one of our opinions. Most people, including me, first learned internal martial arts and qigong with out a Daoist inspired view.

Most people, including me, first learned internal martial arts and qigong with out a Daoist inspired view. traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject keeping in mind its traditional context?

traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject keeping in mind its traditional context? A TRADITIONAL CHINESE ORIENTATION TOWARD KNOWLEDGE.

A TRADITIONAL CHINESE ORIENTATION TOWARD KNOWLEDGE. What is the appropriate attitude with which to approach a traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject of the Internal Arts keeping in mind their traditional context?

What is the appropriate attitude with which to approach a traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject of the Internal Arts keeping in mind their traditional context? I'm calling it concentrated efficiency because that is what it seems like from the outside looking in, but to actually embody either a classic text or a internal arts form feels plain, bland and simple. A traditional Chinese scholar can seamlessly weave a classic, they have memorized, in and out of their speech in such a way that someone who is unfamiliar with the classic won't notice. In fact, scholars who have memorized and embodied many classic texts can play games together where they seamlessly string together classic quotes and yet speak to each other from the heart about things which are important to them. In fact, China has a tradition of scholars with huge appetites for study who can actually quote continuously with genuineness and sincerity. To truly embody an internal practice is the same. On the outside one appears to be doing regular everyday movement, but inside the form (or we could say qigong) is happening all the time, it becomes second nature.

I'm calling it concentrated efficiency because that is what it seems like from the outside looking in, but to actually embody either a classic text or a internal arts form feels plain, bland and simple. A traditional Chinese scholar can seamlessly weave a classic, they have memorized, in and out of their speech in such a way that someone who is unfamiliar with the classic won't notice. In fact, scholars who have memorized and embodied many classic texts can play games together where they seamlessly string together classic quotes and yet speak to each other from the heart about things which are important to them. In fact, China has a tradition of scholars with huge appetites for study who can actually quote continuously with genuineness and sincerity. To truly embody an internal practice is the same. On the outside one appears to be doing regular everyday movement, but inside the form (or we could say qigong) is happening all the time, it becomes second nature. I interviewed George Xu the other day. I expect to have a video of him talking uploaded soon. He said he has video of him demonstrating in Germany that will likely go on the web by October.

I interviewed George Xu the other day. I expect to have a video of him talking uploaded soon. He said he has video of him demonstrating in Germany that will likely go on the web by October. When training in traditional Chinese arts, finding the time to practice consistently, actually setting time aside everyday, is most peoples biggest obstacle. The second biggest obstacle is trying to find a safe comfortable place to practice undisturbed.

When training in traditional Chinese arts, finding the time to practice consistently, actually setting time aside everyday, is most peoples biggest obstacle. The second biggest obstacle is trying to find a safe comfortable place to practice undisturbed. The basic idea of fengshui is that the site itself is the most important consideration. Since you will be taking qi(inspiration) from the environment, the best location is a place you want to be, and that you can come to consistently. A place where you feel safe comfortable and can be alone. It should be a place where the air is fresh(free to circulate) yet still (absence of wind).

The basic idea of fengshui is that the site itself is the most important consideration. Since you will be taking qi(inspiration) from the environment, the best location is a place you want to be, and that you can come to consistently. A place where you feel safe comfortable and can be alone. It should be a place where the air is fresh(free to circulate) yet still (absence of wind).

In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong.

In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong. diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

Chinese Martial arts and Qigong from a Daoist point of view are non-transcendent traditions.

Chinese Martial arts and Qigong from a Daoist point of view are non-transcendent traditions.

Understanding the cultural and historic significance of hair in China will really help give meaning to the underlying metaphors of song.

Understanding the cultural and historic significance of hair in China will really help give meaning to the underlying metaphors of song. Han (ethnic Chinese) males were forced to wear their hair in a cue as a form of national humiliation. If you cut your cue the penalty was death. Historically the cue was used at night by the Jurchen people to tie their slaves to a post. So the term song could easily be understood as harboring some revolutionary bravado.

Han (ethnic Chinese) males were forced to wear their hair in a cue as a form of national humiliation. If you cut your cue the penalty was death. Historically the cue was used at night by the Jurchen people to tie their slaves to a post. So the term song could easily be understood as harboring some revolutionary bravado. Gods also have hair styles. Zhenwu, or Ziwei, is the Chinese god of fate and the central deity of the Chinese pantheon. He is the North Star, the point on the top of your head, and the perfected warrior. He represents the physicality of fearlessness, the perfect mix of pure discipline and extraordinary spontaneity that is the basis for Daoist meditation. In his iconography his hair is song, part of it is tied back in a loose braid with silk and chain to protect his neck from sharp blades, the rest is long and hanging loosely about his shoulders. His hair is a throwback (I couldn't resist) to ancient shaman-warriors who showed their utter lack of concern for status by letting their hair go wild.

Gods also have hair styles. Zhenwu, or Ziwei, is the Chinese god of fate and the central deity of the Chinese pantheon. He is the North Star, the point on the top of your head, and the perfected warrior. He represents the physicality of fearlessness, the perfect mix of pure discipline and extraordinary spontaneity that is the basis for Daoist meditation. In his iconography his hair is song, part of it is tied back in a loose braid with silk and chain to protect his neck from sharp blades, the rest is long and hanging loosely about his shoulders. His hair is a throwback (I couldn't resist) to ancient shaman-warriors who showed their utter lack of concern for status by letting their hair go wild..jpg) The key Taijiquan term peng has generally been translated 'ward-off.' I think that was a good start, after all, in Chinese it is only one word, but it has a really specific meaning so I'm going to try to render it into English.

The key Taijiquan term peng has generally been translated 'ward-off.' I think that was a good start, after all, in Chinese it is only one word, but it has a really specific meaning so I'm going to try to render it into English. your head upwards and your tail bone downwards. Relax your abdominal muscles so that your breathing no longer moves your ribs, but instead moves your lower-back region (mingmen).

your head upwards and your tail bone downwards. Relax your abdominal muscles so that your breathing no longer moves your ribs, but instead moves your lower-back region (mingmen).