Is Ballet a Chinese Martial Art? While such a question may strike some as the outer edge of reasonable scholarship; the facts, when ordered properly and examined thoroughly, speak for themselves.

First of all let’s acknowledge that ballet is Europe’s only classical movement art. India has at least six classical movement arts, Indonesia has more, China has over a hundred.

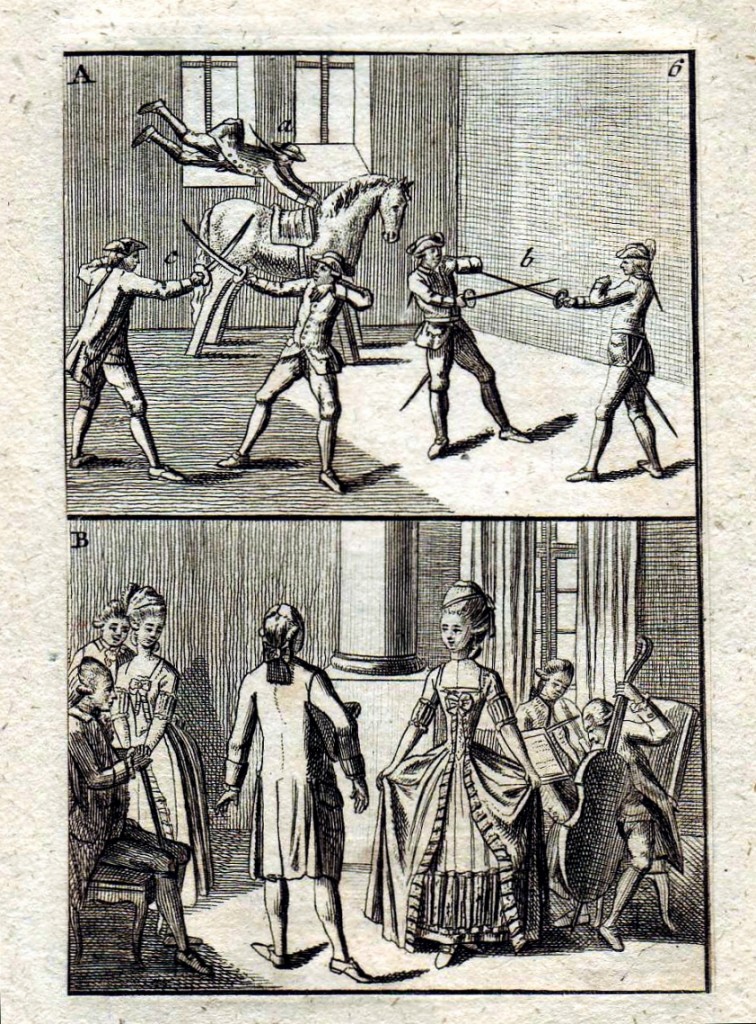

Ballet today is taught to millions of screaming little girls in pink tights. But a couple of hundred years ago it was a man’s art. When Euro-centric scholars have examined the origins of ballet they have looked principally at two sources, folk dance and fight training.

Folk dances are generally divided into the somewhat arbitrary categories of classic, pre-classic, festival, mating, and court dances. There is no doubt that ballet choreography is deeply rooted in the movement patterns of for instance the pre-classic

pavan, the court minuet, and that graceful mating dance, the waltz. But none of these popular culture dances give us any clue as to why the serious study of technical and virtuosic skill characteristic of ballet developed.

Louis XIV in Lully's Ballet de la nuit (1653).

Louis XIV in Lully's Ballet de la nuit (1653).Scholars generally point to

court dances as the origin of all this serious fuss because nearly all the kings and queens and their aristocratic entourages from Spain to England to Russia were getting together for diplomatic shin-digs and princess exchanges. They knew each other and they knew the same dances. So it has been argued that there was a need for a common language of entertainment, and perhaps a common language for male suitors to demonstrate their masculine prowess.

All this is quite possible, but let’s leave it aside for the moment and look at the origins of martial ballet technique.

The European gentry was obsessed with dueling.

I’ve written about this elsewhere but suffice it to say, knowing how to fence by the strict rules of chivalry was part of the definition of the aristocracy. Fencing schools and tutors were all the rage. The basic positions of ballet children learn today, first, second, third, forth, and fifth position, come from fencing, as does the general aesthetic of turned out legs.

Then there is the art of tripping. The basic footwork of ballet has at least some origins in tripping skills. Ballet students do endless demi-plies with the arm in forward, side or back position while the toe rotates around on the floor in a large arc with extraordinary force integrated with the fast kicking action of coup-de-pied. Ballet dancers know how to trip.

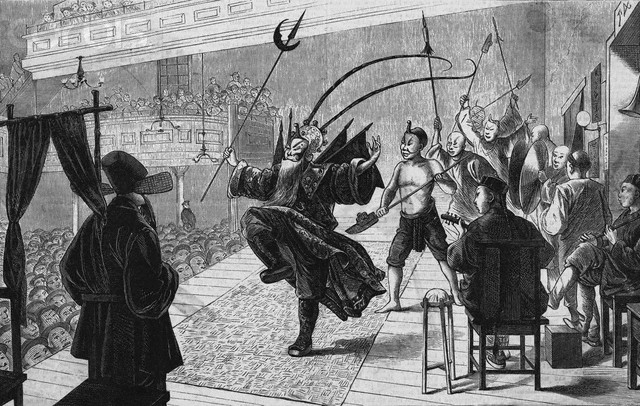

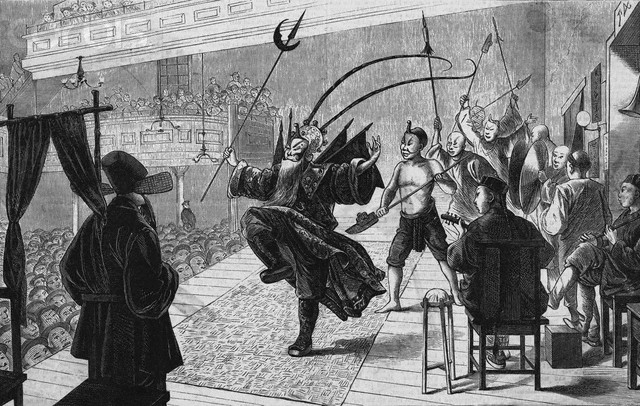

Interior of the Royal Chinese Theatre in San Francisco during a performance in the 19th century. --- Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

Interior of the Royal Chinese Theatre in San Francisco during a performance in the 19th century. --- Image by © Bettmann/CORBISAnother argument about the movements of ballet goes that they have roots in the aristocracies endless formal presentation movements and bows. Know doubt this is true, imagine a lord with his arms held open wide to the sides holding in each hand an eligible maiden trailing a long dress. We’ve all scene this in the movies. And it’s true, the nobles of Europe were obsessed with “presentations.” In fact there is a form of martial presentation which is also given as an origin of ballet. I speak of course of the horse pageant. This parade of power and status spurred an industry of riding schools which taught people how to show off on a horse. You can still

watch this on youtube. Riders doing pirouettes standing up on the back of their horse. It seems fun and silly today, but it was martial in those days. Remember the war horse was both the tank and the fighter jet of the 1600’s.

Yes, OK, you say, ballet has some rambo-tough aristocratic roots, but where does China fit in?

To answer this question we have to consider how they were thinking about China back then. Besides silverware, the two finest things you could own in the 1600’s were blue and white ceramics and silk clothing from China. When you got together with other lords and ladies,

what did you do? Why you showed off your China gear,

that’s what. These items were known as

luxuries. The word luxury has come to mean anything expensive, but in those days it referred to the exclusive possessions of the aristocracy. If you were a wealthy merchant you were expected to wear course wool and rough linen. If you wore silk it was a sin. If you were a successful artisan and drank tea, another luxury, from a Chinese cup, that was a sin too. As global trade increased the aristocracies all over Europe were trying to find ways to visually and viscerally demonstrate their exclusivity and superiority. The more trade increased, the more prices fell, and the more prices fell the more opportunities there were for commoners to get rich. Extortion, the main source of income for the aristocracy, just wasn’t enough to keep the aristocracy on top any more. They became desperate for distinction.

Marco Polo’s account of China was like one of the only books. I know this sounds outrageous but in 1500, before the enlightenment, there just wasn’t much to read. Everyone knew about Marco Polo. Then in 1500 when Jesuit priest

Mateo Ricci went to China, followed shortly by a string of both Franciscan and Jesuit priests, interest in everything Chinese exploded. They don’t teach it in schools but the

enlightenment debate about the possibility that virtue existed outside of Christianity was started by translations of Confucius. After all, if Confucius was talking persuasively about the importance of virtue before Jesus was, could he really have gone to hell?

I don’t know that anyone was taking dictation at parties back then, but imagine the questions you would be asked by members of the aristocracy if you were a priest or a trader returning from a recent trip to China. “So what do the Chinese upper classes do for fun?” “What distinguishes an Chinese gentleman from the common rabble?” You would have, of course, told them about the Ming Dynasty “Scholar’s Cities,” that is, the theater districts just outside city walls that scholars young and old flocked too. “And what sorts of spectacles did they see?” “They saw actors and singers all of whom were trained from childhood in an extraordinary form of physical dance theater. A form of physical dance theater, you add, that demonstrated incredible feats of martial prowess. These ‘dancers’ were cast in history plays where they played great lords and ladies of the past, as well as warlords and youthful heros! Sometimes the fight scenes of these plays were the main attraction!”

“Chinese scholars were obsessed with these arts, in their spare time they were amateur actors and dancers. They would spend long hours singing snippets of their favorite history plays into the night with close friends and bowls of wine. Although a Chinese gentleman would never take money for a performance, it was quite common for them to formally employ a famous actor to tutor them in the arts of singing and martial arts.”

The lords and ladies of Europe invented ballet training as another much needed way to distiguish themselves from commoners. They modeled it on accounts of Chinese martial arts.

I’m not suggesting that there are any direct physical links between ballet training and Chinese martial arts, but it seems quite likely that the idea of Chinese martial arts was in fact the impetus that got ballet off the ground.

---I originally intended this as a parody. I wanted to make fun of the irrational fear many martial artists have of the entertainment roots of their arts. But it says something unnerving about how deep I am in my own well of ideas that I think I just convinced myself of the likelihood of my own conjecture.

I welcome all challenges, serious and otherwise.

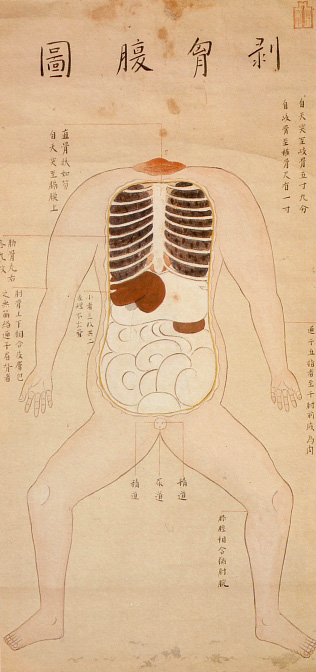

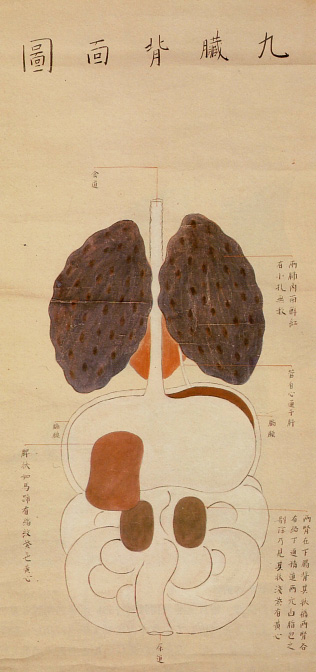

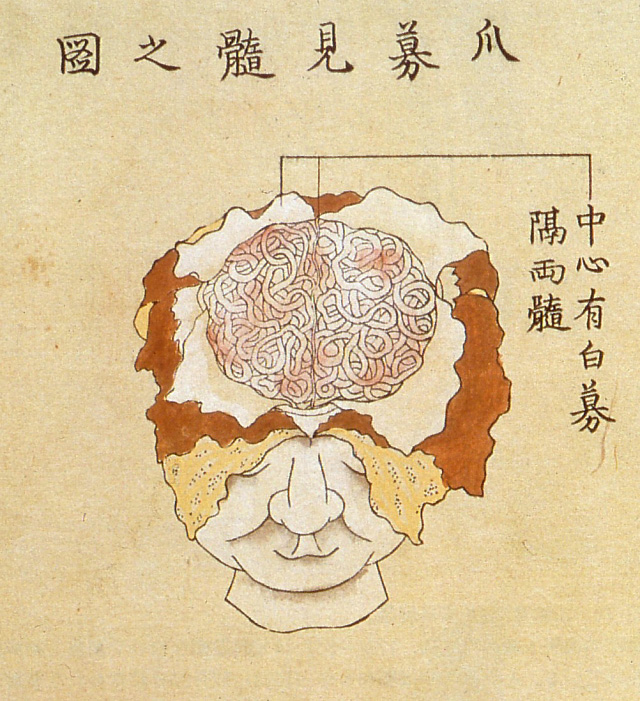

I don't have much of a commentary on this yet,

I don't have much of a commentary on this yet,

Rum Soaked Fist is reporting that Robert W. Smith has passed away. I have not seen any obituaries yet, but he was one of the earliest Westerners to train and

Rum Soaked Fist is reporting that Robert W. Smith has passed away. I have not seen any obituaries yet, but he was one of the earliest Westerners to train and  Update...the Sumo was awesome. Here are my quick observation which are certain to offend someone so let me preface them by saying they aren't meant to offend, just to provoke thinking:

Update...the Sumo was awesome. Here are my quick observation which are certain to offend someone so let me preface them by saying they aren't meant to offend, just to provoke thinking: 7. I have heard from several sources that the Japanese do not think Sumo and Mongolian wrestling are related. I heard for instance, that the squat dance they do with their arms out to the sides, hands together than up then down, is to show that the wrestler has no weapons. But it looks a lot like a version of the Mongolian eagle dance. (check Youtube) Also the side balance with one leg up in the air and then coming down with a heavy stop looks just like Mongolian wrestling. As a demonstration of prowess it has a lot in common with the stamps in Chen Style Tai Chi too. Maybe Mongolian wrestling came from Sumo?

7. I have heard from several sources that the Japanese do not think Sumo and Mongolian wrestling are related. I heard for instance, that the squat dance they do with their arms out to the sides, hands together than up then down, is to show that the wrestler has no weapons. But it looks a lot like a version of the Mongolian eagle dance. (check Youtube) Also the side balance with one leg up in the air and then coming down with a heavy stop looks just like Mongolian wrestling. As a demonstration of prowess it has a lot in common with the stamps in Chen Style Tai Chi too. Maybe Mongolian wrestling came from Sumo?

I don’t know that anyone was taking dictation at parties back then, but imagine the questions you would be asked by members of the aristocracy if you were a priest or a trader returning from a recent trip to China. “So what do the Chinese upper classes do for fun?” “What distinguishes an Chinese gentleman from the common rabble?” You would have, of course, told them about the Ming Dynasty “Scholar’s Cities,” that is, the theater districts just outside city walls that scholars young and old flocked too. “And what sorts of spectacles did they see?” “They saw actors and singers all of whom were trained from childhood in an extraordinary form of physical dance theater. A form of physical dance theater, you add, that demonstrated incredible feats of martial prowess. These ‘dancers’ were cast in history plays where they played great lords and ladies of the past, as well as warlords and youthful heros! Sometimes the fight scenes of these plays were the main attraction!”

I don’t know that anyone was taking dictation at parties back then, but imagine the questions you would be asked by members of the aristocracy if you were a priest or a trader returning from a recent trip to China. “So what do the Chinese upper classes do for fun?” “What distinguishes an Chinese gentleman from the common rabble?” You would have, of course, told them about the Ming Dynasty “Scholar’s Cities,” that is, the theater districts just outside city walls that scholars young and old flocked too. “And what sorts of spectacles did they see?” “They saw actors and singers all of whom were trained from childhood in an extraordinary form of physical dance theater. A form of physical dance theater, you add, that demonstrated incredible feats of martial prowess. These ‘dancers’ were cast in history plays where they played great lords and ladies of the past, as well as warlords and youthful heros! Sometimes the fight scenes of these plays were the main attraction!” Today we mourn the passing of

Today we mourn the passing of It's hard to imagine what the world was like back then, just like it's hard to imagine what it was like when everyone thought the world was flat. Today, "training" is a prerequisite for sports. Before LaLanne, training was a form of cheating! Really!

It's hard to imagine what the world was like back then, just like it's hard to imagine what it was like when everyone thought the world was flat. Today, "training" is a prerequisite for sports. Before LaLanne, training was a form of cheating! Really! I really don't know what to do. Paulie Zink has

I really don't know what to do. Paulie Zink has  I almost always avoid politics on my blog, most of what we call politics is simply too shallow to warrant any overlap with the general topic of this blog. I also do my best to avoid seeming rude, rudeness in other people often turns me off, why would I subject my readers to that? But I'm going to make a small exception for a big issue. (Exceptions prove the rule, right?)

I almost always avoid politics on my blog, most of what we call politics is simply too shallow to warrant any overlap with the general topic of this blog. I also do my best to avoid seeming rude, rudeness in other people often turns me off, why would I subject my readers to that? But I'm going to make a small exception for a big issue. (Exceptions prove the rule, right?) Hey, don't look at me. I'm not crazy enough to take on this question. It is the title of a book by Paul Ulrich Unschuld, who is one of the top scholars on the history of Chinese Medicine and Medical Anthropology.

Hey, don't look at me. I'm not crazy enough to take on this question. It is the title of a book by Paul Ulrich Unschuld, who is one of the top scholars on the history of Chinese Medicine and Medical Anthropology.