If you get a chance to read this article about my trip to

China in 2001 you'll see I ask people lots of questions about religion. At that time, if the subject of religion, TCM, or

qi was raised, 95% of the time I would be asked,

"Xin bu xin?" Xin is one of those Chinese words that means lots of things. Here it means, "do you believe or do you not believe (in qi, TCM, or religion)?" But the word

xin, like our word

faith, could also mean

trust. (It's a little creepy being ask this all the time.)

This pervasive question is new to Chinese culture. As far as I know, it does not get asked in Taiwan. Where did it come from?

Marxism, since

Raymond Aron first pointed it out, has been exposed as having the trappings of a religion. One of the characteristics of Marxism is that it takes its definition of religion from Christianity. Thus despite the fact that Marxism claims to be anti-religion, it defines religion only in Christian terms.

"Do you believe in God? and that...." is a Christian question. Jews, for instance, do not frame religion this way (to Jews it is a series of laws). Neither do Muslims (to Muslims it is an act of submission). Certainly the world's

Animists don't focus on this question either.

Chinese Communists use this "do you believe...?" question to subvert all other forms of authority. Chinese religious traditions do not require belief. Use of the term

qi does not require belief. The practice and efficacy of

any type of

medicine does not require belief.

The practice of martial arts,

particularly, has absolutely nothing to do with belief. I'll even go further. There is really no such thing as

theory.

All we have are lists of experiments and protocols for achieving results. The best that can be said about theory is that it is a tool for inventing new experiments. It doesn't have any real world existance.

By the way, everything I have just said is completely compatible with Orthodox Daoism, except that perhaps I've violated the precept "be uncontentious," or another one, "do not comment on the veracity of claims made by (other) cults."

The Chinese world view was first articulated by the founder of Religious Daoism, Zhang Daoling. A thousand years later, during the Song Dynasty it was adopted by the Chinese Government as Orthodoxy. This world view

posits that all things and events are

mutually self-recreating, there is no external agency. The source of all inspiration and the process by which all inspiration comes into being, is

constantly available.

The role of belief in such a world view does not survive

Occam's Razor. I bring all this up because it is a constantly reoccurring issue. People often think that

belief in qi will somehow improve their Acupuncture treatments. If it works on animals and small children, I think it is fair to say, belief is not a factor.

When training in traditional Chinese arts, finding the time to practice consistently, actually setting time aside everyday, is most peoples biggest obstacle. The second biggest obstacle is trying to find a safe comfortable place to practice undisturbed.

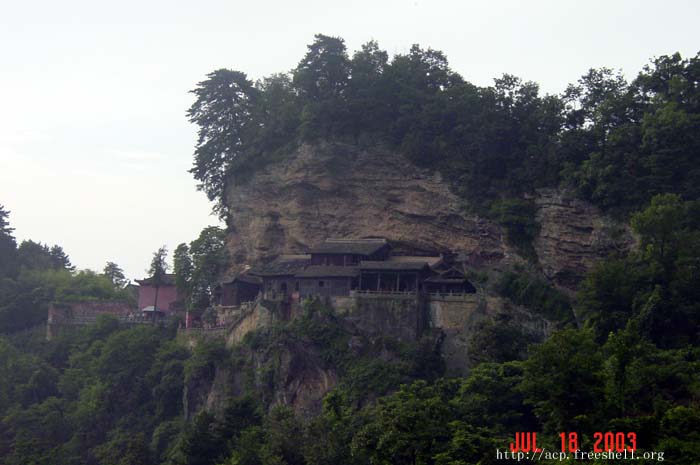

When training in traditional Chinese arts, finding the time to practice consistently, actually setting time aside everyday, is most peoples biggest obstacle. The second biggest obstacle is trying to find a safe comfortable place to practice undisturbed. The basic idea of fengshui is that the site itself is the most important consideration. Since you will be taking qi(inspiration) from the environment, the best location is a place you want to be, and that you can come to consistently. A place where you feel safe comfortable and can be alone. It should be a place where the air is fresh(free to circulate) yet still (absence of wind).

The basic idea of fengshui is that the site itself is the most important consideration. Since you will be taking qi(inspiration) from the environment, the best location is a place you want to be, and that you can come to consistently. A place where you feel safe comfortable and can be alone. It should be a place where the air is fresh(free to circulate) yet still (absence of wind).

In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong.

In general I teach that yin proceeds yang. Structure leads to function. However, the opposite is also true. Where you begin, what you emphasize, will create a different style of qigong. diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

diaphragm in a muscular, sometimes even aggressive way. If I say, "breathe naturally," they become self-conscious ("you mean I'm not breathing right?"). Anxiety leads to tension which produces more restriction.

Chinese Martial arts and Qigong from a Daoist point of view are non-transcendent traditions.

Chinese Martial arts and Qigong from a Daoist point of view are non-transcendent traditions.

If you get a chance to read this article about my trip to

If you get a chance to read this article about my trip to

Jess O'Brien edited together a bunch of interviews with internal martial artists called

Jess O'Brien edited together a bunch of interviews with internal martial artists called  I think my favorite section was the interview with Luo Dexiu where he talks about the cultural barriers he had to get around in order to learn from very traditional teachers. In that traditional setting a direct question would have been perceived as a challenge to the status of his teacher, and his teacher would have gotten very angry. He and his fellow students came up with all sorts of ingenious ways to get questions answered with out actually ever asking a question. At one point he and another student stage angry huff and puff arguments and then ask the teacher to settle them.  This technique got some their questions answered.

I think my favorite section was the interview with Luo Dexiu where he talks about the cultural barriers he had to get around in order to learn from very traditional teachers. In that traditional setting a direct question would have been perceived as a challenge to the status of his teacher, and his teacher would have gotten very angry. He and his fellow students came up with all sorts of ingenious ways to get questions answered with out actually ever asking a question. At one point he and another student stage angry huff and puff arguments and then ask the teacher to settle them.  This technique got some their questions answered. Nam Singh

Nam Singh I took the following quote from Joanna Zorya at

I took the following quote from Joanna Zorya at