Strength and Modernism

/ The worldwide movement called 'modernism' seems to insist on squeezing everything 'traditional' to see what can be extracted of value. This view assumes that what is of value in tradition can and should be extracted from the valueless mumbo jumbo of belief and superstition. What this aggressive view misses when applied to internal arts is that they have already been refined many times- every generation goes through a process of unfolding the material of the past and making it their own. Internal arts, and gongfu in general, are super concentrated already.

The worldwide movement called 'modernism' seems to insist on squeezing everything 'traditional' to see what can be extracted of value. This view assumes that what is of value in tradition can and should be extracted from the valueless mumbo jumbo of belief and superstition. What this aggressive view misses when applied to internal arts is that they have already been refined many times- every generation goes through a process of unfolding the material of the past and making it their own. Internal arts, and gongfu in general, are super concentrated already.When this 'separate out the chafe from the wheat' notion of modernism is applied to qigong, qigong seems to weaken and wither away. If we insist on examining qigong from the point of view of Modern medicine for instance, or sport based athleticism, at best qigong will appear to be mild hypochondria or a fantasy. It will seem too insignificant, too slow, too ineffective, and too boring!

But don't let that get you down. What happens if we turn the table around and use qigong to examine these other two? Modern medicine seems obsessed with inconclusive tests and invasive procedures, it's way too much- way too late. Sports look like competition ind

uced trance, as a way to achieve glory with out sensitivity.

uced trance, as a way to achieve glory with out sensitivity.Such attempts to 'cross reference'-- or as the cliche goes, 'meld east and west'-- are delicate projects which too often bring with them a kind of enthusiasm which lacks sensibility. Fields of knowledge have their own inherent logic only when considered in context. We don't use molecular biology to analyze traffic congestion, or shipbuilding to analyze pastry making. This being said, indulge me in this brief look at what weight lifting is from a qigong point of view. I am often in situations of trying to explain qigong to people who lift weights. Normally I try to use language and terms which bring them into conversation comfortably, rarely do I get to explain what it is like to look out at the world from the perspective of someone practicing qigong. Here goes.

Weight lifters carefully damage muscles and other soft tissues a little bit at a time causing contractions in all the soft tissues around these minor injuries, generally restricting the circulation of qi. This then causes the muscles to grow larger and more rigid in order to reduce future injury to themselves and other soft tissues. Most people do it for the look or the feeling of strength. This suggests that they started out feeling weak, or are perhaps drawn to an idealized image of what they could be. Others lift weights because the work they do or the sports they play are characterized by regular injuries, the added bulk gives them some protection, and the reduced circulation makes it possible to sustain small injuries without feeling them.

The work and exercise people do often leaves a regrettable mark on their bodies. On the other hand, if you are good enough to play for the Chicago Bulls, do it! Why resist? Some fates are easier to unravel than others.

The work and exercise people do often leaves a regrettable mark on their bodies. On the other hand, if you are good enough to play for the Chicago Bulls, do it! Why resist? Some fates are easier to unravel than others.If my arguments seem to strong, perhaps there is a resolution. Daoism has always held that there needs to be many different ways for different people to fulfill their natures and that despite apparent differences we are all participants in a larger collective body and we actually need each other to be different in order to support a community, or a community of communities. The world is big enough for many different ways of being. My guess is that weight lifting has its true roots in the skillful wielding of heavy weapons and that perhaps what seems like two diametrically opposing views actually has a resolution in the practice of martial arts, something close to my heart.

If after reading this you still wish to lift weights, my suggestions are: Be graceful, develop evenly, and use loss of movement range as a measure of when you've gone to far. I will venture that the real distinction between muscular strength and muscular tension is: Strength happens where you want it to happen, tension happens where you don't want it to happen.

In the practice of qigong we do not want strength or tension and we tend to follow this simple adage: If it feels like strength-- it's tension! Qigong practitioners are adept at releasing unwanted tension from anywhere in their bodies.

The perfect expression of a Daoist practice is simultaneously resolving and inspiring. Inappropriate conduct leaves things (qi) unresolved. Appropriate conduct resolves things (zhengqi). Unresolved ancestors manifest through the actions of those still living -- their descendants. Thus, we can see religious merit or gongfu, as the practice of resolving our ancestors inappropriate conduct through our own appropriate conduct. (

The perfect expression of a Daoist practice is simultaneously resolving and inspiring. Inappropriate conduct leaves things (qi) unresolved. Appropriate conduct resolves things (zhengqi). Unresolved ancestors manifest through the actions of those still living -- their descendants. Thus, we can see religious merit or gongfu, as the practice of resolving our ancestors inappropriate conduct through our own appropriate conduct. ( In recent years a lot of qigong that is popularly taught has been categorized as martial arts qigong. (I think it is mistake to use this category in the first place, but if we do use it we will have to divide it up further.) This would be qigong created by and for people who were put in the position of needing to fight.

In recent years a lot of qigong that is popularly taught has been categorized as martial arts qigong. (I think it is mistake to use this category in the first place, but if we do use it we will have to divide it up further.) This would be qigong created by and for people who were put in the position of needing to fight. xing yi and bagua. This type has the flavor and reluctance characteristic of those who cultivate weakness. In this tradition the battle field is viewed as an expression of qi. The battle field substitutes for the body in which the smooth flowing of qi is a priority, not avoiding war, but being uncontentious. Looking for resolution is different than trying to win, although winning may be necessary for your survival. This is not a passive tradition, in fact attacking first can easily be the quickest cleanest resolution with the least loss of life on both sides. How this tradition came about is an interesting question I plan to continue exploring. Perhaps people who had been cultivating weakness, were drafted and this was a natural expression of their circumstance. This third traditions takes the longest to develop usable skills, and seems like a privileged position with in a military world.

xing yi and bagua. This type has the flavor and reluctance characteristic of those who cultivate weakness. In this tradition the battle field is viewed as an expression of qi. The battle field substitutes for the body in which the smooth flowing of qi is a priority, not avoiding war, but being uncontentious. Looking for resolution is different than trying to win, although winning may be necessary for your survival. This is not a passive tradition, in fact attacking first can easily be the quickest cleanest resolution with the least loss of life on both sides. How this tradition came about is an interesting question I plan to continue exploring. Perhaps people who had been cultivating weakness, were drafted and this was a natural expression of their circumstance. This third traditions takes the longest to develop usable skills, and seems like a privileged position with in a military world.

What is it like watching most older people move? Is it a source of pity or sympathy, or perhaps a foreboding omen of what we can some day expect ourselves? If we were to study older peoples' movements with respectful inquisitiveness what might we learn?

What is it like watching most older people move? Is it a source of pity or sympathy, or perhaps a foreboding omen of what we can some day expect ourselves? If we were to study older peoples' movements with respectful inquisitiveness what might we learn? Some guy named Jerome Weng in Singapore responded to my Youtube video

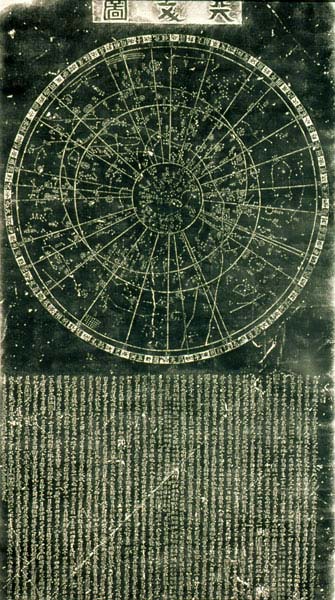

Some guy named Jerome Weng in Singapore responded to my Youtube video  know eight palm changes which correspond to the eight trigrams, you can practice each hexagram too. Think of each hexagram as a transition between two trigrams and practice that transition. (So for example, hexagram 63 is li [fire] transitioning into kan [water].) On divination days, improvise!

know eight palm changes which correspond to the eight trigrams, you can practice each hexagram too. Think of each hexagram as a transition between two trigrams and practice that transition. (So for example, hexagram 63 is li [fire] transitioning into kan [water].) On divination days, improvise! What do daoists do? It can be divided up into three categories: Conduct, Hygiene, and Method.

What do daoists do? It can be divided up into three categories: Conduct, Hygiene, and Method. Practitioners of these so called "long-life" practices, reach their peak level of performance in their 60's and 70's.

Practitioners of these so called "long-life" practices, reach their peak level of performance in their 60's and 70's. Another possible source of gongfu is as a form of physical training to survive trance. As I've already said, the trance-medium tradition was pervasive in China for most of its history. Full-on possession by a god, as happens in both African religion and Chinese religion, is extremely taxing on the body. Wild movements may toss, whip, shake and gyrate the possessed person. I suspect that at some time in the distant past, this experience was a near death one; people who were repeatedly possessed had shorted lives. Yet in Africa as in China people who become possessed have extraordinary physical training which allows them to survive, some even with radiant health. In Africa this training is dance, and in China, at least in Taiwan and the South East Asian Chinese Diaspora, it is gongfu.

Another possible source of gongfu is as a form of physical training to survive trance. As I've already said, the trance-medium tradition was pervasive in China for most of its history. Full-on possession by a god, as happens in both African religion and Chinese religion, is extremely taxing on the body. Wild movements may toss, whip, shake and gyrate the possessed person. I suspect that at some time in the distant past, this experience was a near death one; people who were repeatedly possessed had shorted lives. Yet in Africa as in China people who become possessed have extraordinary physical training which allows them to survive, some even with radiant health. In Africa this training is dance, and in China, at least in Taiwan and the South East Asian Chinese Diaspora, it is gongfu. This is also one of my favorate explanations for the difference between internal and external martial arts (neijia and waijia). In Africa and the African Diaspora, priests and drummers are required to be familiar with the rituals for each deity and his/her particular characteristics. For instance, a particular deity is invoked through specific rhythms, dances, songs, and sacrifices. A deity might be known for being jealous, carrying a sword, being female, being associated with the color green, having a sharp wit, and of course, wielding power in a particular realm. However, both priests and drummers are forbidden to become possessed by the deity. Should they become possessed they lose their ritual statues. They are experts in managing and differentiating the different types of human trance.

This is also one of my favorate explanations for the difference between internal and external martial arts (neijia and waijia). In Africa and the African Diaspora, priests and drummers are required to be familiar with the rituals for each deity and his/her particular characteristics. For instance, a particular deity is invoked through specific rhythms, dances, songs, and sacrifices. A deity might be known for being jealous, carrying a sword, being female, being associated with the color green, having a sharp wit, and of course, wielding power in a particular realm. However, both priests and drummers are forbidden to become possessed by the deity. Should they become possessed they lose their ritual statues. They are experts in managing and differentiating the different types of human trance. forbidden to become possessed yet their training involves becoming intimate with each type of trance. Daoism is, among many things, a systematic ordering of all types of deities by the characteristics of their local or national cults--and by the specific types of trance that lead to possessions by particular deities.

forbidden to become possessed yet their training involves becoming intimate with each type of trance. Daoism is, among many things, a systematic ordering of all types of deities by the characteristics of their local or national cults--and by the specific types of trance that lead to possessions by particular deities.