Theory and Metaphor in Martial Arts

/I’ve been trying to write about theory for a few weeks. The problem is simple, but explaining the problem is not. The problem is that martial arts theories are built on metaphors. Notice that in the previous sentence we have three metaphors. “Built” is the most obvious one here, implying that a foundation is laid followed by a construction project. Another metaphor in the sentence is “problem,” implying perhaps a puzzle requiring contemplation, or alternately an agent causing systematic disruption. In addition we have “martial” and “arts” nagging for explication, “martial” implying war, and “arts” implying the harnessing of beauty while piling up skills.

But if we look back at that sentence the most challenging term is “metaphors.” All theory is built on metaphors, mental constructs in place of actual experiences. Someone might protest at this point that martial arts can only be based on physics. But physics is made up of metaphors too; we are a liquid body of mass filled with solids of various densities, structured along lines of potential force and contained by a semi-porous wrapping with an elastic surface tension. To make that description of the human body useful in martial arts practice it has to be both simplified and abstracted so that possibilities and probabilities can be measured and predicted. It is a lot more efficient and useful to just say, “Your finger on the end of your arm is the pool cue, and his eye is the ball.”

Metaphors are always imperfect because kinesthetic experiences are far more complex than language. I suppose someone might want to challenge that statement, but even if we could speak in a language as complex as kinesthetic experience it would have to be robust enough to survive the learning and testing process. And then there are mundane concepts like communication breakdown.

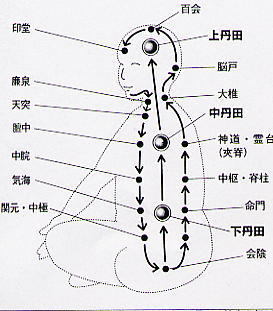

So it follows that if we clearly understand a metaphor and we diligently put it into practice, it will fail. It will fail because it was imperfect to begin with. It was an inaccurate description of form, method and fruition. A quick example: Many martial arts schools use the metaphor of circulation, but all the substances which are known to circulate in the body circulate too slowly to be useful outside of passive processes. If in this case circulate is meant to refer to forces from an opponent being returned to the opponent, the liquid aspect of the metaphor “circulate” is an inadequate description of the aspects of structure and mind necessary to accomplish this function.

The majority of Tai Chi classes are containers for the trivial. I recently heard about a teacher who had created three “new” tai chi forms, one for diabetes, one for Alzheimer's, and one for Parkinson's disease. My first thought was, “Wow, cute.” No doubt there is some talismanic effect from self-selecting to learn and practice a form which has a specific health benefit. Unless of course you are that person who thinks, “Hey, I did my my diabetes form today, bust out the triple chocolate cake!”

In most of these trivial classes the students simply follow the teacher through the form and get an occasional posture correction. The same metaphors are repeated ad nauseum; relax, root, flow, spiral, sink, be stable like a mountain, flow like a river.

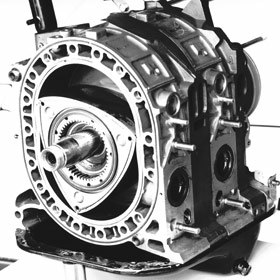

The same is true for most martial arts classes. There is very little metaphor analysis going on. Some schools frown on talking in class at all. Some students just want exercise, their base metaphor being, “I am a machine that gets rusty and needs motion and heat (oil?) to maintain optimal functioning.” Some schools cater to parents metaphorical expectations that their child will become either a robotic fighting machine or a caring disciplined servant of all that is true and good. Some schools take enormous pride in maintaining the same metaphors over time. Some schools are proud of their simplicity, others of their clarity. The more systematic the approach, the more entrenched the metaphors will be.  Rotary Engine

Rotary Engine

Thus, those of us who can actually think kinesthetically are constantly changing the metaphors we use. We need to use one metaphor to test another. The process involves continuously reformulating and refining the metaphors we use, while also pairing and juxtaposing them to birth new metaphors and kill off old ones.

The process of training should allow metaphors to be replaced by precise feelings and experiences. But both the maintenance of skills as well as the teaching of skills requires that metaphors function as containers for kinesthetic knowledge. The same is true for those metaphors which define our identity. The freer we are, the freer we are to change and adapt the metaphors we live by.

The identity piece is also important because the martial arts we practice transit between cultures which often have different deeply embedded metaphors which can act either as lubricants or friction in the transmission of ideas. (For example Chinese language posits that time is a man facing backwards, while English posits time is a man facing forwards.)

I know for sure that if a teacher can describe a kinesthetic experience with perfect clarity it is wrong and it will fail. It may however, be very, very useful.  Lion's Head Meatballs

Lion's Head Meatballs

Playing with Majia and swords yesterday, she offered the metaphor that if you put your arm too far out to the side it will get ground up in a blender. Metaphors are so much fun. George Xu has a similar one; cut off your opponent’s arm with your spinning airplane propeller. He has a whole bunch of new and unusual metaphors, as well as reformulated and recycled ones. For instance, be a giant meatball hanging in the sky. (I believe he is referring to Lion’s Head Meatballs, yum!) Or, be a tree trunk falling on your opponent when you chop. Also, use your rotary engine against his piston engine. And, punch him with three heads and six arms while being empty like Romeo staring at Juliet as it begins to snow.

Please share your favorite martial arts metaphors.