A Parade in India 15 Miles Long

/I saw this video on Youtube and it reminded me of the huge culture shock my girlfriend and I got on our first night in India.

We checked into a hotel early in the AM and went to see sights around the capital Delhi. As we left the hotel we looked down the long road our hotel was on and saw some elephants coming our way in the distance. Wow, "We're in India," I thought, I guess elephants are normal here.

We tried to return in the early evening but inexplicably no one would take us back to our hotel, so we had to walk. As we got closer, the number of people in the streets started to multiply. As we got within a couple of blocks of our hotel, the streets were packed. A man with a turban, took

my arm and said, "Sir, I don't want you to get the wrong idea about my people, we are a good people." "What do you mean?" I asked. "Who are your people?" "I am of the Sikh religion, and I am a professor. This is why I am telling you." he said as he disappeared into the crowd.

As we got to the street where I hoped our hotel was we heard music, and singing; a lively parade was going down the street; it was now dark. The road was thick with people on foot but also elephants and cars and buses and flatbed trucks, all with people on them shrieking and throwing candy (ouch!).

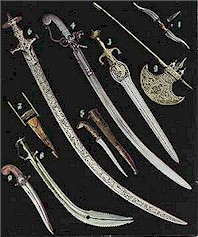

Now, I knew, that it was a requirement that at all times, men of the Sikh religion are required to carry a knife. However, in this parade most people had something longer than a knife-- swords, spears, halberds, shields, I even saw a morning star.

I suppose it would have been less intense if we were just watching, but we really

wanted to find our hotel and with all the distraction is was really difficult. We went back and forth many times looking for the hotel sign, in the direction the parade was moving, and against the tide.

There was food stuff for sale in the shops along the sides, which in India spill out into the street, so it was really tough squeezing through, and no joke, some of the shops had vats of boiling oil we had to maneuver around! All this chaos meant that my girlfriend and I got separated several times.

I suppose even this would have seemed cute if the weapons weren't actually being used. But they were. People were dancing wildly with their swords, jousting with their spears (a la the video!) and playing various versions of what we used to call on the playground, "chicken." Except it was "armed" Chicken.

At one point I was walking with some guys with broad swords and one of them grabbed my arm and asked, "What religion are you?" My blood ran cold, "American," I said after hesitating. "But what religion?" he asked over and over, and each time I answered the same thing, "American." I pretended not to speak English and finally made a dash for my hotel.

I later learned that this was a 15 mile long parade with over a million Sikhs. It was explained to me that if someone swings a sword at you, naturally you duck, and if it misses this is because God has protected you. If not, not.

Ahhhhhh a little bit of warrior code, and a little bit of shamanic power.

When I saw a book titled,

When I saw a book titled,  This is a continuation of my discussion of

This is a continuation of my discussion of

This is a continuation of my discussion of Warriors,

This is a continuation of my discussion of Warriors,

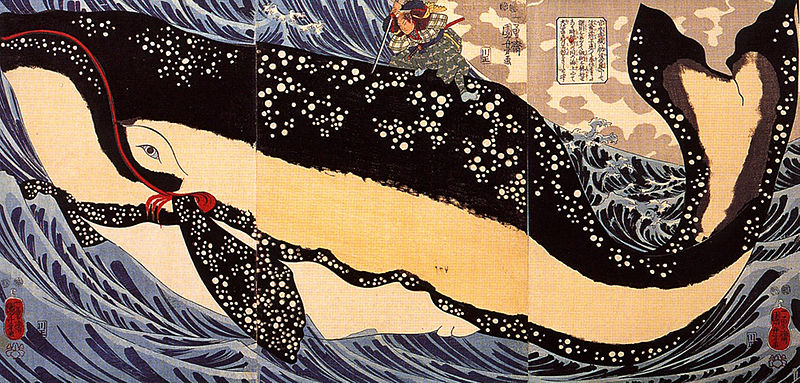

code, a Samurai needed only two things, fearlessness and a willingness to die. The change from Warrior to skilled technician and martial artist is marked historically with the life of

code, a Samurai needed only two things, fearlessness and a willingness to die. The change from Warrior to skilled technician and martial artist is marked historically with the life of

after the parts I think are the strongest, the points that are most central, and are the most likely to change one of our opinions.

after the parts I think are the strongest, the points that are most central, and are the most likely to change one of our opinions. Most people, including me, first learned internal martial arts and qigong with out a Daoist inspired view.

Most people, including me, first learned internal martial arts and qigong with out a Daoist inspired view. traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject keeping in mind its traditional context?

traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject keeping in mind its traditional context? A TRADITIONAL CHINESE ORIENTATION TOWARD KNOWLEDGE.

A TRADITIONAL CHINESE ORIENTATION TOWARD KNOWLEDGE. What is the appropriate attitude with which to approach a traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject of the Internal Arts keeping in mind their traditional context?

What is the appropriate attitude with which to approach a traditional Chinese subject? How do we go about the process of unfolding the subject of the Internal Arts keeping in mind their traditional context? I'm calling it concentrated efficiency because that is what it seems like from the outside looking in, but to actually embody either a classic text or a internal arts form feels plain, bland and simple. A traditional Chinese scholar can seamlessly weave a classic, they have memorized, in and out of their speech in such a way that someone who is unfamiliar with the classic won't notice. In fact, scholars who have memorized and embodied many classic texts can play games together where they seamlessly string together classic quotes and yet speak to each other from the heart about things which are important to them. In fact, China has a tradition of scholars with huge appetites for study who can actually quote continuously with genuineness and sincerity. To truly embody an internal practice is the same. On the outside one appears to be doing regular everyday movement, but inside the form (or we could say qigong) is happening all the time, it becomes second nature.

I'm calling it concentrated efficiency because that is what it seems like from the outside looking in, but to actually embody either a classic text or a internal arts form feels plain, bland and simple. A traditional Chinese scholar can seamlessly weave a classic, they have memorized, in and out of their speech in such a way that someone who is unfamiliar with the classic won't notice. In fact, scholars who have memorized and embodied many classic texts can play games together where they seamlessly string together classic quotes and yet speak to each other from the heart about things which are important to them. In fact, China has a tradition of scholars with huge appetites for study who can actually quote continuously with genuineness and sincerity. To truly embody an internal practice is the same. On the outside one appears to be doing regular everyday movement, but inside the form (or we could say qigong) is happening all the time, it becomes second nature. I interviewed George Xu the other day. I expect to have a video of him talking uploaded soon. He said he has video of him demonstrating in Germany that will likely go on the web by October.

I interviewed George Xu the other day. I expect to have a video of him talking uploaded soon. He said he has video of him demonstrating in Germany that will likely go on the web by October.